On Saturday, Sharon Clements arrived at the Southwest Baltimore building that houses Baltimore City Robotics Center to pick up laptops.

Greeted by Ed Mullin and Jonathan Moore, Clements talked about how the devices would help the families she works with as children’s program director of Dayspring Programs. The East Baltimore nonprofit helps families experiencing homelessness find housing and offers substance abuse treatment services. The families, she said, have an apartment and a desk set up so children can complete school work and are connected to the internet. But many are using their mother’s phones, which have small screens, and are bound to get interrupted when a call comes in.

The seven laptops — which were set to be distributed to families with multiple children — would give them a dedicated device to complete their work: “This should take away one of the barriers that the parents have,” Clements said.

The laptops themselves were donated by Baltimore businesses and community members. Mullin has been telling everyone he can that any laptop they’re no longer using could have a new purpose, and conducting porch pickups. Then, they’re refurbished to run on Linux by a group that includes Mullin and friends from the IT community, as well as technologist Adam Bouhmad of Baltimore’s Project Waves. On Saturdays, the trio has been scheduling pickup times with community organizations.

It’s part of the work of DigiBmore, a group that formed in the current crisis. DigiBmore found a particular need to support families in underserved areas when social distancing measures forced schools to close and immediately brought challenges for students who weren’t connected at home. But the broader work didn’t just begin: The cofounders — Mullin, Bouhmad, Moore, Digital Harbor Foundation Executive Director Andrew Coy and TEDCO Portfolio Manager McKeever Conwell — have known each other for years.

So it wasn’t surprising that they found themselves on the same social media thread when Conwell shared an article about digital access issues. They have an acute awareness of the issue.

Mullin, for instance, works with plenty of precocious students in Baltimore robotics leagues. At the same time, he also sees many who don’t have laptops at home.

“They want to learn,” he said. “They would be watching Khan Academy classes and all sorts of stuff.”

The DigiBmore members also have experience working on various aspects of bridging the digital divide. After all, Baltimore’s digital disparities didn’t start with the pandemic.

In 2020, digital access is a key indicator for a city’s health. Look no further than the annual Vital Signs report from the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance-Jacob France Institute (BNIA) at the University of Baltimore, which since 2017 has included data on devices and internet access down to the neighborhood level.

It shows the following for the city:

- Approximately 18% of households lack access to a computer, cell phone or tablet

- About 6% of households have access to only a smartphone, but not a computer or tablet

- Approximately 24.6% of households do not have access to internet at home

To put it in numbers, a much-referenced digital equity report from the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation from 2017 found that 74,000 families in the city lack access.

Within that data, there are signs of the gaps, said BNIA Associate Director Seema Iyer. There are some communities where fewer than 5% of households do not have internet at home, and others where nearly half of households do not have internet access, she said.

Check out BNIA’s map showing which Baltimore neighborhoods have internet and device access:

The divides are similar to those in many other areas of life in Baltimore, be it economic, housing or health. They grew out of racist policies that started nearly 100 years ago, and continue in the internet age.

“It’s the haves and have nots,” said Moore, who’s CEO of RowdyOrbit dev bootcamp. “We’ve identified what the Black Butterfly is and we talk about what the Black Butterfly is about, but there’s still several different Baltimores, and these Baltimores are really disconnected. When people talk about Baltimore, it’s, ‘What Baltimore are you talking about?’ The Baltimore that exist in the white L does not exist in the Black Butterfly.”

And there are gaps between Baltimore and other cities. Iyer cites figures that show in San Jose, California, 75% of people who make $25,000 or less have internet access. In Baltimore, that number is 52%.

There are disparities among cities and then we have disparities in our own city.

“There are disparities among cities and then we have disparities in our own city,” she said.

In a time when so many functions are online, it brings challenges on multiple levels. One was already coming into view before the pandemic: Iyer said BNIA originally created the above map to show where folks would have a hard time responding to the 2020 census, which moved mostly online this year.

In the pandemic, it takes on a new function as a starting point to look at how the city can maintain connectivity. Whereas schools, libraries, community and rec centers and offices served as places for folks to get access and help to close that gap, now we’re limited to the devices and connections at home.

And amid social distancing orders, it’s only more acute. The data show that most people have access to a smartphone, which might have been able to suffice as a supplementary tool. But with work becoming remote, now it’s the primary.

“You can’t go to school and do online learning on a smartphone nearly as well as if you have at least a tablet or a laptop,” Iyer said. “If you are trying to work at home you can’t do that without any kind of device, if you can remote work at all.”

To think about what the barriers would be like, Coy issues a challenge: “Imagine you didn’t have the internet. How long would [you] last?”

Netflix binges, Zoom happy hours, remote yoga sessions — all of those things that have helped get you through the pandemic would be out. Telehealth visits and video calls with therapists that have shifted online during social distancing, too.

“It’s really easy to forget that’s a luxury,” Conwell said.

And then there are the tools that help work get done in an age of remote work and distance learning.

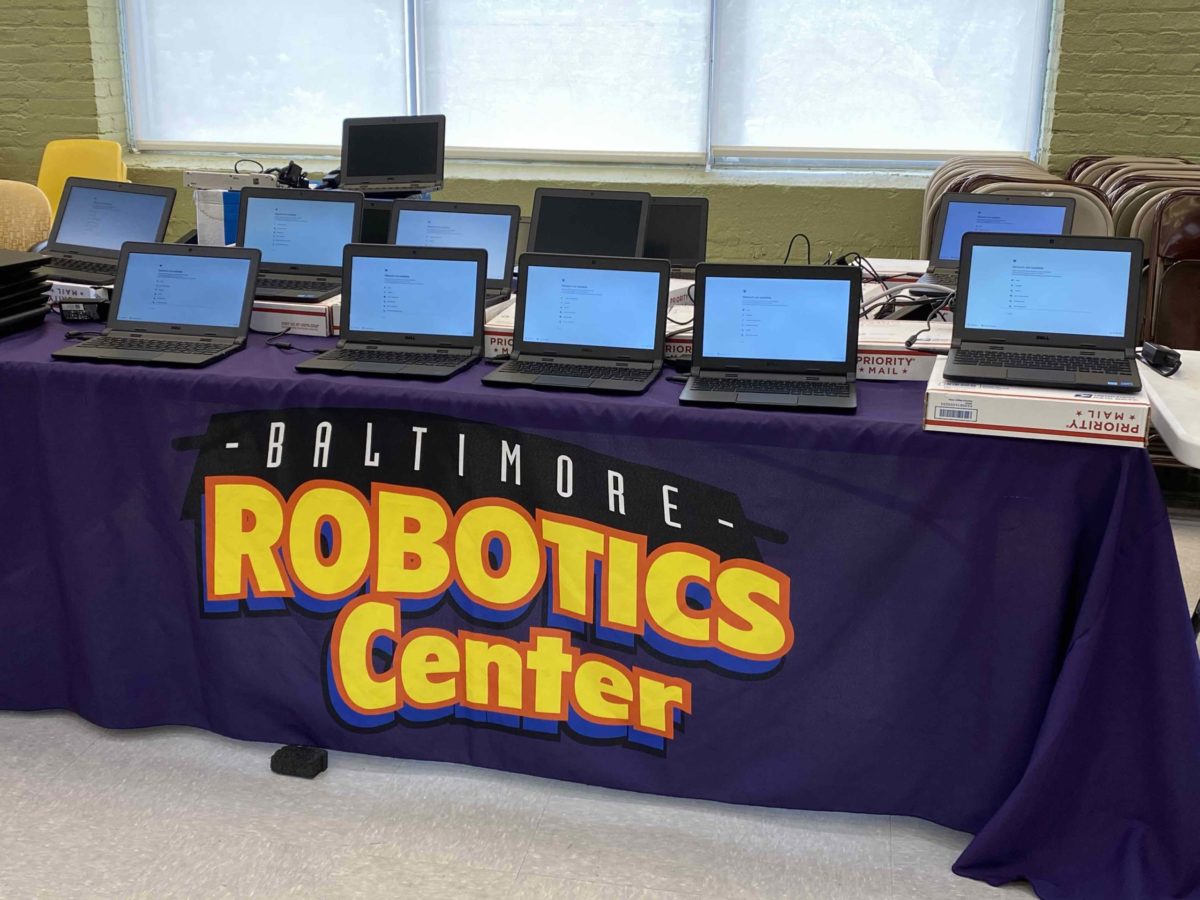

Donated laptops at the Baltimore Robotics Center. (Photo by Stephen Babcock)

Like other schools across the state, Baltimore City Public Schools closed its buildings in mid-March. With stay-at-home orders set to remain in place at least until the middle of May, the district entered remote learning on April 6. Access to Google Classroom and video lessons were among the resources listed to help provide connections in lieu of classroom time, so the need for devices to use those tools became imperative.

So along with moving instruction online, the district has been mounting a big effort to distribute devices. At an event with U.S. Sen. Chris Van Hollen on Wednesday, Baltimore City Schools CEO Sonja Santelises said the district purchased more than 12,000 Chromebooks to go along with 27,000 devices it had on hand. They distributed devices first to juniors and seniors, and have distributed to 75% of students so far.

Distance learning also brought change for tech education. Byte Back is shifting its computer education classes virtual and looking to add more in Baltimore after an expansion last year. At the same time, it’s also ensuring devices and connectivity are in place for all students, said Communications Director Yvette Scorse.

I hope the result of all this is that we can make changes that impact students longer term for the better.

Station North-based computer science education nonprofit Code in the Schools moved its Prodigy program to a remote model, and putting together computer science classes in Python and game development that can be accessed for free, said CEO Gretchen LeGrand. At the same time, they’ve been taking into account that those resources can’t get accessed without device and a connection, and so are offering help to students who lack them.

“This crisis that were facing and that students are facing, and [asking] how do they have equitable access to education when they can’t leave their home, I think, could be a turning point in how we think about equitable access to everyone for internet devices,” LeGrand said. “I hope the result of all this is that we can make changes that impact students longer term for the better.”

With life changing seemingly overnight, it brought a need for immediate response. In some cases, that meant those with resources could extend them. Comcast, which is the city’s primary broadband provider, made its already-low-cost Internet Essentials program free to many who qualify for public assistance programs for two months.

Yet in an issue area where the problem is well understood, it also means that the initiatives that took shape to work on systemic change are stepping up.

In the grassroots collaborations that come together, it helps if the organizers bring their own talents and resources to help move quickly. For DigiBmore, Mullin’s tech skills and ability to galvanize the business community help to procure 150 devices. It’s taking on a Robin Hood feel, as he talked about how one IT business bought 25 Chromebooks on eBay, and sent them to the Robotics Center.

It’s also a way to pitch in: For folks that want to help during the pandemic, one way is to dig through a closet and find an old laptop to donate.

Moore is focused on outreach within the neighborhoods where there are needs: “How do we engage communities and how do we work with community organizations, because once we give the device, how are they using it?” So he’s connecting with community organizations like Dayspring that understand the needs of their communities.

What I'm interested in is identifying communities that aren't getting reliably stable internet and aren't necessarily about to afford it, and providing essentially a way that they can pay what they can.

And there’s planning for scale. At Digital Harbor Foundation’s Federal Hill tech center, Coy said there was already a tech lending library established geared around the nonprofit’s maker programming, with support of grant funding from the France-Merrick Foundation. As part of DigiBmore, that can be a place where refurbishment and distribution of laptops happens on a bigger scale, and Digital Harbor Foundation can help with matching students in need. There’s also talk of setting up help desk-like services to follow up with recipients.

Once the laptop is up and running, the other piece of the equation is connecting to the internet. Bouhmad has long believed that internet should be a public utility, meaning that equitable access is a must. It’s something he started working on with Project Waves, a community internet service provider that sets up mesh networks to bring connectivity to families in areas where there is lower access. He set one up node at Digital Harbor Foundation to serve families in Sharp-Leadenhall.

“What I’m interested in is identifying communities that aren’t getting reliably stable internet and aren’t necessarily about to afford it, and providing essentially a way that they can pay what they can and is championed at the community level,” Bouhmad said.

On Saturday, the Robotics Center became one of those neighborhood-level nodes as a new connectivity point was activated for Southwest Baltimore. After climbing up a couple of ladders to the roof of the building, Bouhmad talked us through the two sector antennas and a third 360-degree antenna that make up the connection point. Meanwhile, on the ground, a collaborator drove around to test it. Sure enough, it was up and running, offering access for folks within a two-mile vicinity.

“They’ll be able point over here and get internet,” Bouhmad said.

At a person’s home, Project Waves can provide the materials to get connected and, via DigiBmore’s work, will be able to include a laptop.

Ed Mullin and Adam Bouhmad light up Project Waves for Southwest Baltimore. (Photo by Stephen Babcock)

Meeting folks where they are is a key tenet for Libraries Without Borders, too. Last fall, the nationwide organization teamed with Baltimore organizations including Enoch Pratt Free Library and the Deutsch Foundation to launch the Wash and Learn Initiative. It turned four city laundromats into tech access points, offering a chance to tap into connectivity and resources while waiting for clothes to finish spinning.

With the pandemic, not as many people are hanging out inside laundromats, but they remain essential businesses where folks are heading to clean their clothes. It brought new thinking for Libraries Without Borders.

“For communities that we’re already serving, how can we meet people where they are and provide what folks are looking for?” Executive Director Adam Echelman said.

So the org is offering refurbished devices to families with whom it already had relationships with, and working to connect via partnering organizations. To offer connectivity, it’s also creating hotspots that extend Wi-Fi from inside the laundromats into parking lots.

When it’s the place you can go to connect for school or work, it brings a whole new meaning to “essential” — something the DigiBmore folks would surely agree with.

Join our growing Slack community

Join 5,000 tech professionals and entrepreneurs in our community Slack today!

Donate to the Journalism Fund

Your support powers our independent journalism. Unlike most business-media outlets, we don’t have a paywall. Instead, we count on your personal and organizational contributions.

Maryland firms score $5M to manufacture everything from soup to nanofiber

National AI safety group and CHIPS for America at risk with latest Trump administration firings

How women can succeed in male-dominated trades like robotics, according to one worker who’s done it