This profile is part of a series on Black creative and entrepreneur expats — why they left, and what Philly could do better to keep the next generation.

Jon Gosier gets plenty of use out of his tuxedo.

In recent years, the tech founder and sometimes angel investor has gone deeper into the worlds of film and music. Scan his recent social media posts for selfies with directors, producers and doers at the Cannes Film Festival. He pops up in Miami, Atlanta and abroad. But you don’t see many shots of Philadelphia from the early alumnus of Dreamit Ventures and a former Philly Startup Leaders board member.

Beginning in 2018, he split time between a home and office in Philadelphia with Atlanta, where had previously lived — and where he found an orbit of film and media financiers. Philadelphia once looked like an ideal home base for this entrepreneur and sophisticate, with a growing network in a city with culture, an international airport and a skip to moneyed circles.

In a diverse, old and poor big city, Gosier was an example of Black wealth in dynamic economic circles. According to a forthcoming analysis by Technical.ly, the percentage of high-income Black Philadelphians grew between 2009 to 2019, but more slowly than their white counterparts in Philadelphia and than Black residents in other cities. Fitting national trends, the pandemic has been a mixed bag for Philadelphia: The city did see one of the country’s fastest growing rates of tech workers but also failed to make gains in right-sizing racial wealth inequality.

What does Gosier think Philadelphia ought to learn about his departure? Much was circumstantial, but he sings a familiar tune: Philadelphia’s investment class seem to be more focused on preserving existing wealth than creating and leading that which is new. It’s something Philly’s promising tech economy has been contending with for years.

Growth stage

If we want more Black tech founders, maybe we should ask Tyler Perry.

Early in his career, Gosier worked in Atlanta with the entertainment mogul’s “Diary of a Mad Black Woman.” As the film’s assistant engineer, Perry’s intrepid business savvy inspired Gosier.

“I was in rooms where he was closing deals,” Gosier told Technical.ly. “It was like being part of a rocket ship when it’s taking off. He inspired me to go do my own [thing].”

Meanwhile, Gosier didn’t have formal technical training, but learned how to code on his own. He moved to Uganda and started AppRica, a consultancy hiring African engineers that counted customers at global tech giants such as Google, Facebook and Twitter. AppRica’s success also put Gosier on the radar of Ushahidi, a successful tech company in Kenya with the investment support of eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.

Ushahidi specialized in data work, and working with the company helped Gosier hone his data science and analytics skills to the point where he developed an industry profile as an expert. In 2011, he left Ushahidi and moved to Philadelphia when his new company Metalayer received funding from the now defunct Minority Entrepreneur Accelerator Program (MEAP). That program provided business owners of color with resources, connections and mentorship from both Comcast and Dreamit.

“They literally brought me to the city,” he said. “I was fairly well known in tech and they brought me here plus a bunch of other companies.”

MEAP offered Gosier the opportunity to learn more about the tech space as a businessman. He continued to build his network in Philadelphia and beyond — later joining the Philly Startup Leaders board as part of a revamp of the prominent nonprofit led by well-connected tech founder Bob Moore.

Exit phase

Gosier was gaining prominence for his business and eventually investing acumen. Business Insider called him one of the “Most Influential African Americans in tech” in 2013; Time named him one of “12 new faces of Black leadership” in 2015.

Gosier later founded Audigent, an adtech startup he sold in 2017. Selling Audigent gave him the financial freedom to work on the projects that captivate him today, including getting active in venture capital and angel investing.

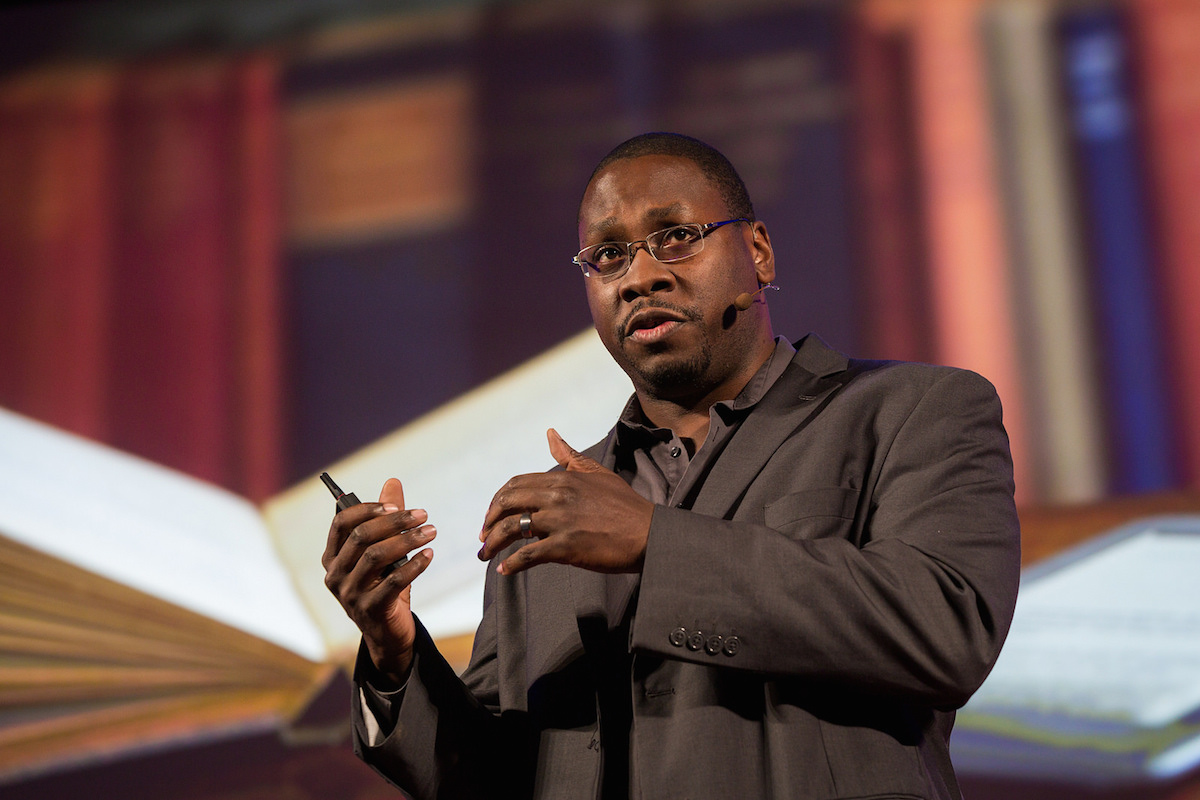

At the kickoff of the Tomorrow Tour in Philadelphia; Gosier is onstage at left. (Photo by Ryan Olah)

In each of his ventures, including those started and founded here, he seldom attracted local investors. Even with his small investment from Comcast and more funding from Dreamit Ventures, Metalayer bootstrapped the rest of its operating funds from customers — none of whom were in Philadelphia. That was just the sort of thing that Bruce Marable, another prominent Black early-stage tech founder in Philadelphia, has felt challenged by.

With Audigent, Gosier said his seed round only counted Ben Franklin Technology Partners as a Philly investor. (Over time, the startup sans Gosier raised more than $33 million, including a recent Series B led by the GO Philly Fund, which is backed by Ben Franklin and EPAM Systems.)

“In my very successful businesses, only 10% of overall capital came from Philly investors,” Gosier said. “This is why people leave. We’re here but all our support comes from elsewhere. I found it difficult to stay.”

Why does closeness to capital matter? So much of investing is about building relationships, and proximity helps, even in the newly remote-first world. It also helps in identifying local issues to solve and attracting local customers, and is a sign of encouragement for other local companies that they can find support, too.

“The venture business is a relationship game,” as Kyp Sirinakis, managing partner of Bethesda-based venture fund Epidarex Capital, put it during a Baltimore Innovation Week 2021 panel about that similarly challenged mid-Atlantic city. “Being able to have investors that know what they’re doing, that have scalable pools of capital, that can roll up their sleeves and put money to work is actually quite important in trying to grow an ecosystem.”

New strategy

Of course, Gosier also represents a success: He was lured to Philadelphia without ever having ties here. He grew companies, paid taxes and made friends over years. Likewise, longtime watchers of Philly startups and economic change here, might call Gosier’s gripes about investors and local customers an old tune. Remote work has appeared to help Philadelphia attract tech workers, and video calls have made raising investment and attracting customers from anywhere easier than ever. It might even sound dated to those who know Philadelphia is now home to three newly minted unicorn tech companies.

But Gosier says this tune isn’t old, it’s just not been addressed.

It’s hard to ignore his point that these challenges are especially acute for founders of color in a majority-minority city like Philadelphia. Though it’s a national crisis, Philadelphia founders in particular report that accessing resources to build sustainable businesses is difficult here, as founders such as LeRoy Jones and Donna Allie have told us. Though many targeted resources do exist for these entrepreneurs in the city, it remains a challenge to find early institutional support, mentorship and support for capacity building.

It’s a problem others have acknowledged. It’s also one attracting active consideration in the local biz-building community. Philly Startup Leaders quickly raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to be funneled to underrepresented founders in the midst of last summer’s racial justice movement. Or take the forthcoming Black Business Accelerator or University City Science Center VC arm as two of the latest efforts to boost support for founders who are often less connected to traditional funding or resources, in additional to those longstanding efforts from the likes of Ben Franklin and Comcast.

These efforts came too late for Gosier. Now back in Atlanta, where he is an active film financier, he considers the Philly investment community to be risk averse, making it unwelcoming to local startup founders who may not have proven themselves yet. Back when he was getting started here, even with global success, Gosier quickly observed that investment from Philly funders often came with some sense of familiarity — say, an investor and founder had worked together before, or gone to school together.

Likewise, Gosier’s choice of Atlanta was no certain fate. That city actually saw less growth in Black high-income earners between 2009 and 2019 than Philadelphia, according to that forthcoming Technical.ly analysis. But like the film industry that keeps Gosier in tuxedos, you need a good story. That means what Gosier says and what other entrepreneurs and tech workers — especially those of color — hear matters a lot.

“Once you succeed, all the big money wants to talk to you,” he said. “All the smaller investors are sitting on the sidelines to get big. For a startup struggling for survival, all that means is you go to where you have to to succeed. Investors risking on something new — that’s not Philly’s investment profile.”

_

This story was edited by Julie Zeglen and Chris Wink.

Michael Butler is a 2020-2022 corps member for Report for America, an initiative of The Groundtruth Project that pairs young journalists with local newsrooms. This position is supported by the Lenfest Institute for Journalism.Before you go...

Please consider supporting Technical.ly to keep our independent journalism strong. Unlike most business-focused media outlets, we don’t have a paywall. Instead, we count on your personal and organizational support.

3 ways to support our work:- Contribute to the Journalism Fund. Charitable giving ensures our information remains free and accessible for residents to discover workforce programs and entrepreneurship pathways. This includes philanthropic grants and individual tax-deductible donations from readers like you.

- Use our Preferred Partners. Our directory of vetted providers offers high-quality recommendations for services our readers need, and each referral supports our journalism.

- Use our services. If you need entrepreneurs and tech leaders to buy your services, are seeking technologists to hire or want more professionals to know about your ecosystem, Technical.ly has the biggest and most engaged audience in the mid-Atlantic. We help companies tell their stories and answer big questions to meet and serve our community.

Join our growing Slack community

Join 5,000 tech professionals and entrepreneurs in our community Slack today!

The person charged in the UnitedHealthcare CEO shooting had a ton of tech connections

From rejection to innovation: How I built a tool to beat AI hiring algorithms at their own game

Where are the country’s most vibrant tech and startup communities?