Nestled among leafy, West Philly streets is the palatial, 186-year-old Overbrook School for the Blind, where on an average Tuesday afternoon, you can find students like Marques “Joey” Perez typing away on his BrailleNote.

Joey, who is blind, sits in the middle of the classroom and chats with a group of four other students from professor Evangeline Worsley’s class. He’s messing with Louis Toole, who is partially blind, because Toole, 15, found it challenging to operate a computer through screen-reading software alone. They shut off the monitors and relied only on the synthesized speech that guides the way.

“I think it’s a good experience for them to know what we have to put ourselves through every morning,” Perez said.

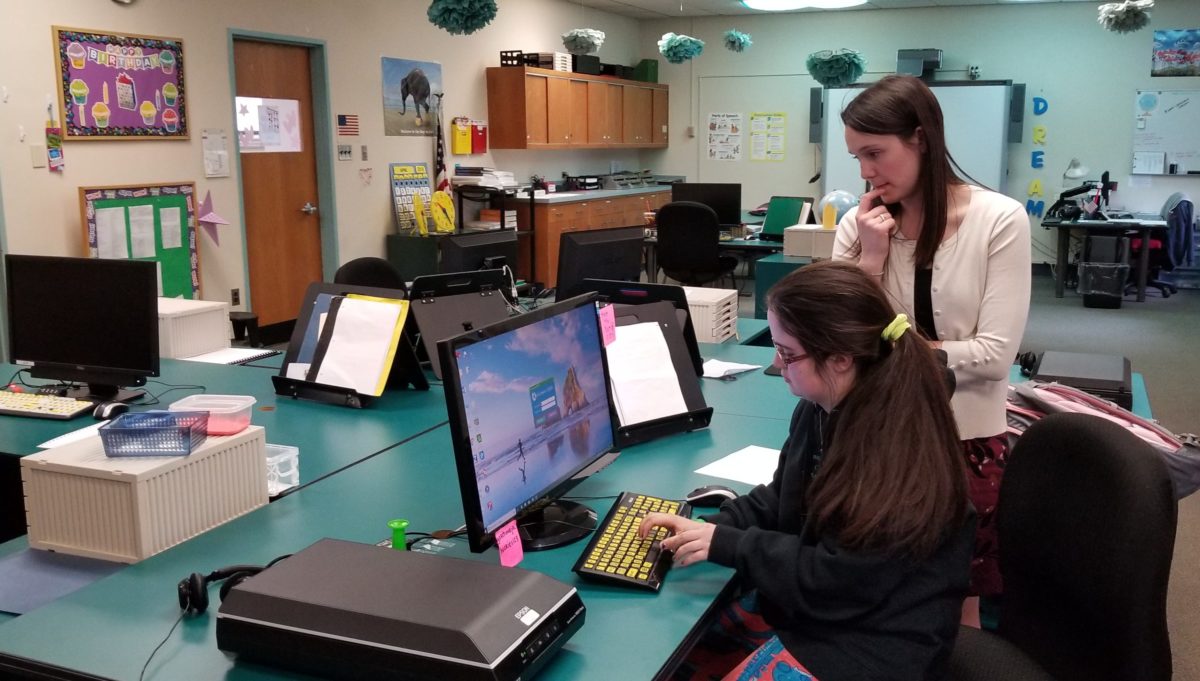

The large schoolroom is peppered with tech tools. There are tablets with text-magnifying software, BrailleNotes — simply put, a laptop that’s operated through braille — and computers outfitted with synthesized speech guidance. On student’s phones, there are applications that recognize text on signs and pieces of paper and read it back to the user. The students use them all with ease, but Denise Mihalick, training specialist at the school, wants you to know that they’re not there to just master the tech.

“The focus with all our technology is access to curriculum,” Mihalik said. “If they’re not getting to the lesson, there’s no point. We prefer for the technology to eventually become somewhat invisible, the way it is for us.”

Students at Overbrook have individualized education plans, where students work with teachers to set goals for themselves according to their base skills and degree of visual impairment.

“Instruction for them is going to look different in every classroom depending on their age and their needs are,” said Worsley, 27.

But as students get more acquainted with tech, they also have to build skills in solving for a different equation: Kids must learn to identify when tech goes wrong, and how to work their way around it. When asked what was wrong with a website they visited recently, Perez is quick to identify the fault: sometimes sites just won’t work with the screen reader and his skills are therefore rendered useless.

“What was wrong was… you couldn’t read it,” Perez said.

From organizations like Overbrook to corporate giants like SAP and Comcast, Philly technologists and advocates are working to bridge the gap so that access to technology means true access for everyone.

###

Inside an office in Spokane, Wash., a team of 75 Comcast customer reps highly trained on things like closed captioning, voice guidance and other accessibility features are the ones to answer the phone for all calls related to users with disabilities.

They can help sort through issues with connectivity, read users’ bills to them so they can understand them and even login remotely (with the customer’s approval) to set-top boxes so they can troubleshoot if something is wrong.

It’s one of several ways Comcast has been working to reach out to differently-abled customers, said Tom Wlodkowski, the company’s VP of Accessibility. Blind since birth, Wlodkowski skillfully demo’s Comcast’s X1 voice-controlled remote to pull-up content with audio description on a TV screen inside the company’s Accessibility Lab on the 35th floor of Center City’s Comcast Center.

His team cuts across customer engagement, product capability and infrastructure to make sure accessibility is part of all new tech offerings.

“We just didn’t have that several years ago,” said Wlodkowski. “Things have changed in the sense that we’ve taken accessibility into the design phase and carried it through. If you’re a User Experience (UX) person, you’ll be dealing with accessibility; if you are a developer, you’ll make sure to mark up your forms correctly. We see it as an area for innovation where using the minimum bar is not really sufficient to build an inclusive experience, so let’s see how we can push further ahead.”

For accessibility consultant Mikey Ilagan, who works for Think Company but is embedded in Wlodkowski’s team, the field’s breadth is a major draw. Since accessibility intersects with different types of products and teams, there’s a great variety of things to work on.

“Wherever people interact with technology, the need for digital accessibility is present,” Ilagan said. “Lastly, as someone who’s experience is mostly web, the opportunity to innovate on the X1 platform is something unique for this line of work and can only be done at Comcast.”

###

The extra step in accessibility starts with prototyping. Wlodkowski said the lab is working on text-based input experience aimed at deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals, like those served by Swarthmore, Pa.-based Deaf-Hearing Communication Centre (DHCC), a nonprofit that offers translation services and outreach for people how are deaf and heard of hearing.

DHCC Executive Director Neil McDevitt helps bridge an important gap for the deaf community by offering quick access to interpreting services, both on-site and via video. It’s the main revenue driver for the 45-year-old nonprofit, which employs 13 full-timers and 170 independent contractors.

“This way you have an almost-instant access to an interpreter,” McDevitt said.

There are pros and cons, though. Think of the ubiquitous ease of the video translation service to American Sign Language as one of the tools in the toolkit, one to break out for quick conversations. In certain scenarios, like where internet access is spotty or there are complicating medical factors, an in-person translator is the ideal choice.

“I have one client who had a traumatic brain injury, and the hospital kept trying to put an iPad in his face so he could see the translator,” McDevitt said. “Problem is: he couldn’t move. It was a bad experience for him because it wasn’t the right usage for that particular scenario. Like a lot of tech issues, there are shades of gray. It’s a hammer when you sometimes need a screwdriver.”

###

Often, accessibility discussions will skew towards physical disabilities, particularly in technology. For software giant SAP, whose North American HQ is just outside of Philadelphia in Newtown Square, the approach also includes bringing neurodiversity into the mix through its Autism at Work program

Trenton, N.J., native Jeff Wang is 27, and was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome and Autism at an early age. As part of the company’s Autism at Work program, Wang — who has a degree in History from Rutgers University — underwent training and mentoring to go an unlikely route for a history major: he became a Human Resources associate at a tech company.

Mostly, Wang’s day-to-day involves project management and general office work, providing support in onboarding new staffers.

Two things made it easier for Wang to overcome the traits of his two conditions and fully join the workforce at SAP: The approach to the job interview process and a program called the “Buddy system.”

“Every new employee, regardless if they’re autistic or not, have a buddy assigned who serves as the point of contact in case management isn’t always accessible,” Wang said. “I was assigned a very kind, resourceful and knowledgeable buddy who I would turn to for feedback. The first couple of weeks or months can be overwhelming, but to have that buddy figure for every employee to show the person the ropes really helps.”

For the interview process, rather than quiz potential employees on what they can do, members of the Autism at Work program are asked to build and program robots with Legos.

“It’s a unique alternative to the traditional Q&A,” Wang said. “It helped to show our strengths and show our willingness to work as a team.”

###

Back at the Comcast lab, Wlodkowski shared more thoughts on what the future of accessibility (often abbreviated online as a11y) could look like.

“We’ll see a lot of personalized experiences going forward, which should benefit accessibility,” Wlodkowski said. “Also, a broader awareness of accessibility as new technology develops. My ideal is that we don’t have to work so hard to catch up to where the state of the art technology is, and that accessibility is threaded in throughout because more people see the value of multimodal experiences.”

Another plus for bringing accessibility front and center in technology? It’s a good for the resume in a tech job market that is hungry, not just for engineers but for many different professions surrounding tech.

“The problem is that we don’t see accessibility as part of computer science,” Wlodkowski said. “We need to start teaching the people who are building these products to become familiar with guidelines and native accessibility solutions for your platform of choice. Find out and be curious as to how you can take advantage of those products.”