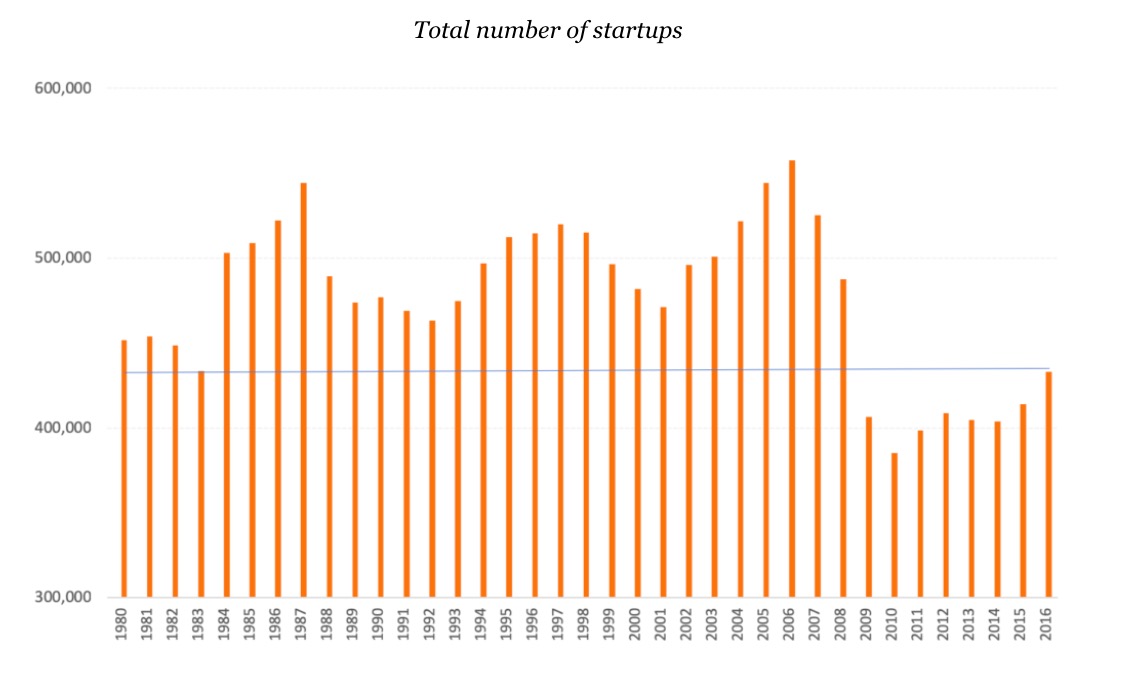

Rates of entrepreneurship have been declining in the United States since the 1970s. Recessions don’t always help.

Though many know the big tech platforms that came out of the Great Recession, and the companies that came from past economic declines and even the Depression, that’s not the prevailing truth, certainly not over the last generation.

For all the entrepreneurship cheerleading of the last 15 years, the Great Recession accelerated an already alarming decline in new business formation in this country. In the United States, our rates of entrepreneurship have been declining for decades, and those new firms that have been created are employing fewer and fewer people.

- In 1980, 15% of all U.S. firms had been created the year before. In 2011, that share had been halved, according to census data.

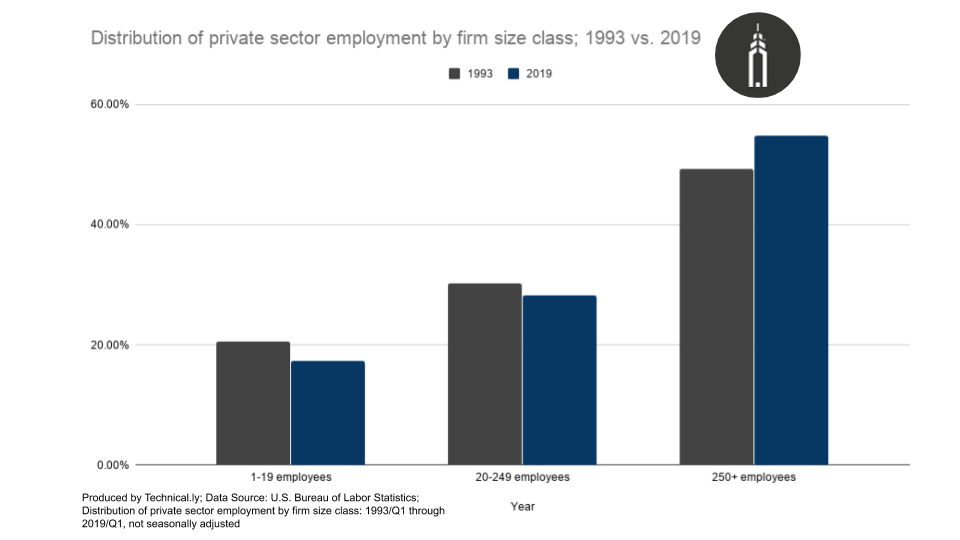

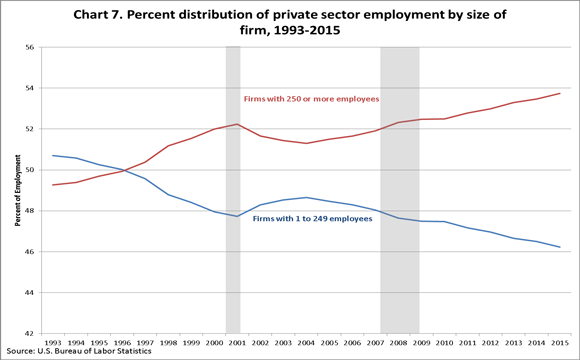

- In 1997, for the first time in this country’s history, more Americans worked at companies with 250 or more employees. The gap has steadily grown since, aside from a notable blip in the early 2000s. The biggest single percentage increase was between 2007 and 2008, as the Great Recession took hold.

- Three-quarters of U.S. incorporations that we do have issue no payroll, mostly for the self-employed.

- Though our outsized venture capital market means we have a high share of iconic, rocket-ship growth companies, the United States is lagging other rich country peers in the crucial middle category: new, growing, innovative companies trying to bring efficiencies to industries that may last.

Recessions tend to crush small firms worse than bigger firms, and today we are almost certainly already in a deep, sustained global recession. Knowing the trend was already away from small and new firms, what’s going to happen this time?

In supply chain business theory, academics might see this adverse impact on small firms as an example of the “bullwhip effect,” in which decisions by large firms (to pull back on spending, for example) can radiate wildly down to ever smaller suppliers. Bigger firms, even zombie ones, tend to have more options for liquidity.

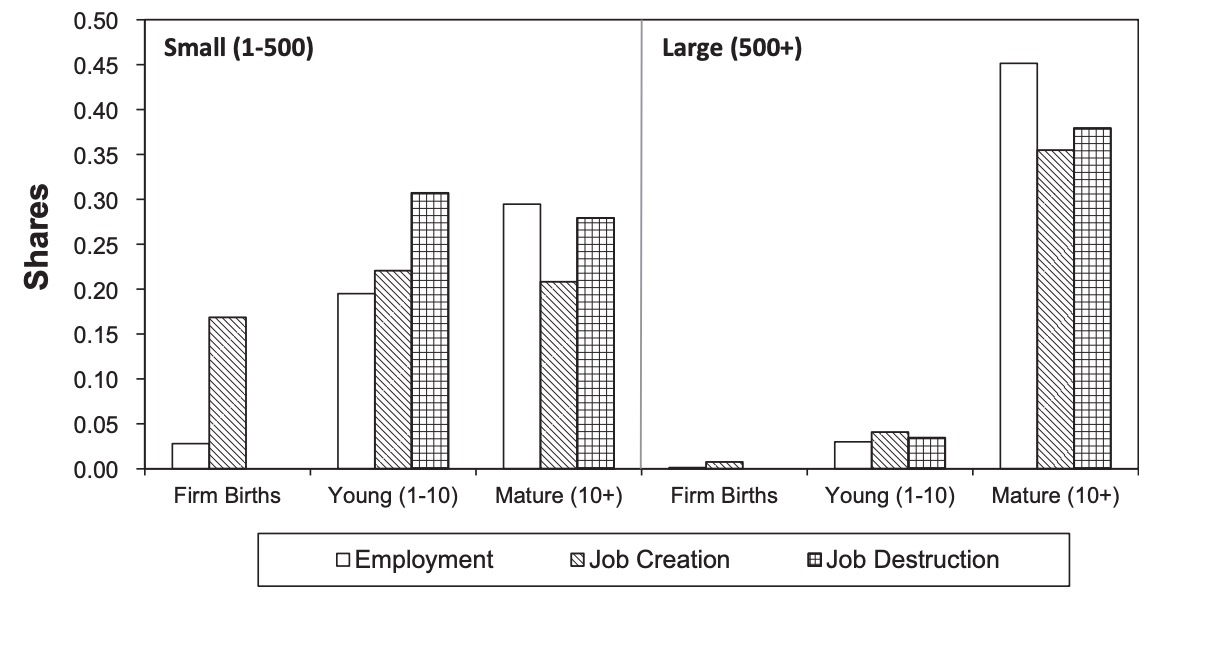

Startup firms create most net new jobs

It’s important to make clear that for most economists and government statisticians, the definition of “startup” is simply any new firm incorporation. That includes everything from a freelancer’s new sole proprietorship to a small firm that might last long but won’t grow quickly all the way to a new company that plans to grow rapidly, whether through financing or sheer innovation.

Though treated the same, it’s the last example of a fast-growth startup that has the most economic impact.

As the Kauffman Foundation has long heralded, it isn’t just small businesses that an economy needs but new businesses. Nearly all net new jobs and almost 20% of gross job creation come from new firms, according to an influential paper published by MIT in May 2013.

It’s hard to track fast-growth startups in government data. You can see in Bureau of Labor Statistics data that in 2019, 10% of employed Americans worked at firms with between 20 to 49 employees, another 10% with 100 to 249 and 40% with at least 1,000 employees. But a fast-growth company could be in any of those categories. For the quantum mechanics fans, fast-growth firms are waves, not particles.

Competition from startup firms create productivity gains

But it’s gotten harder and harder to survive as one of those superstar growth firms, amid growing corporate strength.

It’s true that if a company grows quickly enough it will graduate from small business to large business (a threshold that the U.S. Small Business Administration puts at 500 employees). But the embedded assumption is that new firms scale when they find a new market niche, that will either serve customers well or force existing incumbents to adapt.

It’s also true that on the whole larger firms are more efficient than smaller ones, helpful to contribute to economic growth. That much is not unique to the United States, as other countries have found traditional family firms (no matter their size) tend to be less efficient than their more modern corporate peers.

Though cherished, family-run Japanese firms tend to decline in productivity over successive generations enough that they even have a saying for it in Japanese that translates to “the third generation ruins the house.” The same goes for South Korean Chaebols, that country’s own family-run conglomerates. Even celebrated German Mittelstand firms have trended away from their family-run origins.

New firm competition is a foundation of quality of life gains and economic growth. Declining rates of new firm incorporation may be partially blamed on rising near-monopolies and duopolies. As FiveThirtyEight put it in 2014: “Corporate America Hasn’t Been Disrupted.”

Small firms remain a part of cultural heritage

Cold efficiency misses a very human element, too. Beyond just the jobs created and the competition served, there’s an element of culture. The neighborhood bar, corner restaurant or family-run hardware store are thought to be what makes a place special.

The perceived inefficiency of small businesses can mirror community values and result in serendipity. Traditions are often maintained exactly because they are impractical.

Of course in this particular economic shock, these kinds of neighborhood institutions are the frontlines of what could be a grim wave of closures — with businesses owned by women and people of color at particular risk. A quarter of small U.S. firms hold less than a month of cash reserves. Fortunately, just one in 10 Americans work at companies with fewer than 10 employees; in contrast, nearly half of Italians and Australians do. In a report on the preparedness of rich countries to weather this major recession, The Economist noted this minor role of small firms as a strength for the United States.

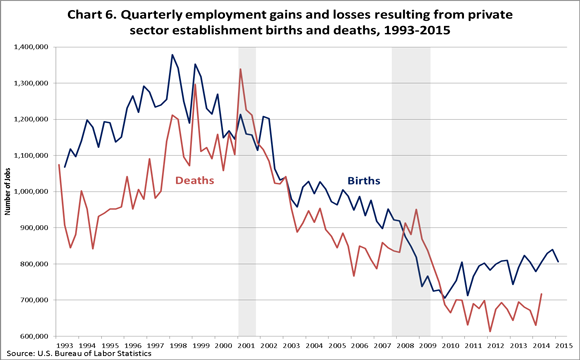

If we do see a corresponding rise in firm closures now, it would at least shake up a dismal flattening over the last decade — as both new firm births and deaths have declined, we’ve seen a worrying calcifying of entrepreneurship.

So what can be done now?

The causes are muddled. Declining rates of immigration, consolidating industries by software-backed network effects, and cultural and demographic factors all play a role. The clear worry is that if the Great Recession sped this decline, and if we haven’t yet found its most specific root causes, this pandemic-caused economic shock could do worse. That would further hurt this country’s job growth, economic competitiveness and cultural heritage.

It’s a worrying alarm to know the economic lifeboat is already leaking before the storm hits. But that also means it’s a known problem that many have worked to address.

The Kauffman Foundation has become a national leader on the topic. It champions an array of salves, from more welcoming immigration policy to simplified tax policies and investing in local entrepreneurship communities. The Kansas City, Missouri-based foundation gives an annual State of Entrepreneurship address.

Though they remain an optimistic bunch, it’s clear declining rates of entrepreneurship was a daunting nationwide challenge before a pandemic. Now attention to small business and new firm creation will become more, not less, important.