In the oncoming labor battle between man and machine, man can look to Greenpoint’s Hype Machine as one example, at least, of a space where us ol’ sapiens still got it on the bots.

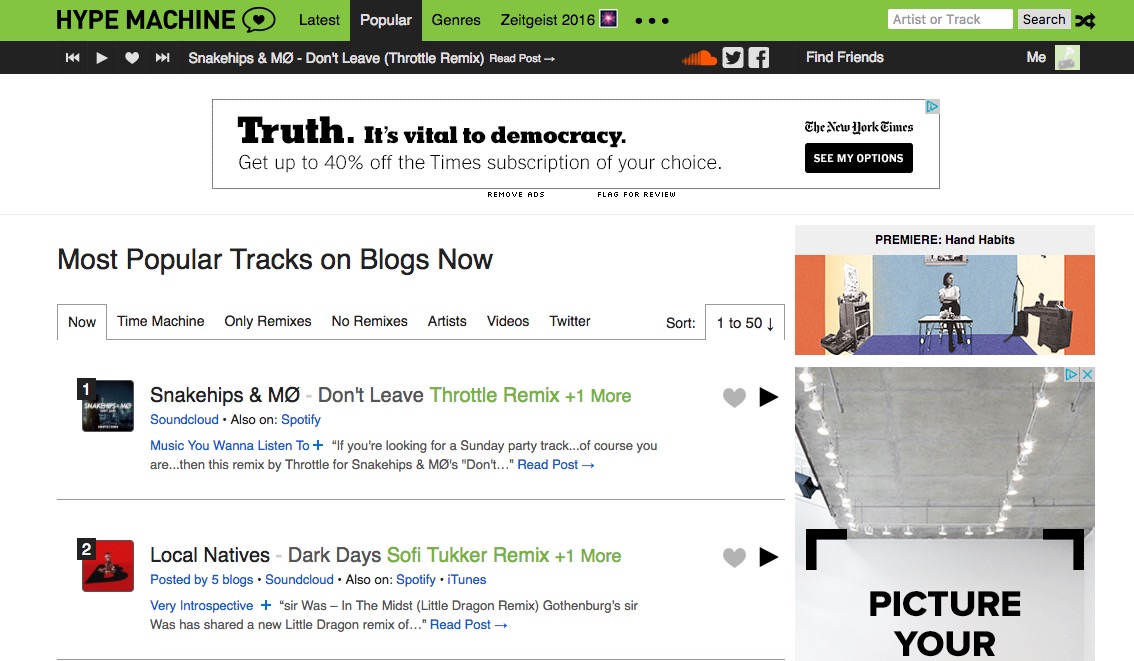

The Greenpoint-based Hype Machine is a website that conglomerates music blogs and forms music charts out of what the blogs are covering. The more blogs are writing about a particular song, the higher it is on the Hype Machine’s Popular chart. As music blogs tend to be on the early adopter side of the industry, the songs you hear on the Hype Machine’s popular playlist are unlikely to be those you hear on the radio, or Spotify for that matter.

“What we’re solving for is that people don’t know what to listen to,” Hype Machine founder Anthony Volodkin said recently over coffee in Greenpoint. “And this problem persists. In our case we give you suggestions based on what everyone is writing about. We don’t care about your existing preferences, we want to show you what’s out there. We were doing that before and it still makes sense today because the platforms that people are using for music don’t really do a good job with that.”

Volodkin started the Hype Machine in 2005, which, for scale in internet time, means that the site predates Twitter. He started it as a 19-year-old undergrad at Manhattan’s Hunter College, as a tool just to help himself find new music.

“You’d get this magazine and you’re reading about stuff that already happened a month ago,” Volodkin explained. “Printed media at the time also felt so connected to the very lucrative music industry. It felt kinda weird and blogs were exciting cause it was a very different approach, they just write about stuff they were into.”

But there were a lot of them. A whole universe of them, really.

So Volodkin made a tool to index what they were writing about. The first version of Hype Machine was really just an RSS feed of what the blogs were covering, he said. Volodkin emailed the program he built to a handful of people to see what they thought, and from there his experience seems to have reflected that of future unknown bands who suddenly finds themselves at the top of the Hype Machine’s chart.

“They got really excited about it and posted it and it got picked up in Del.i.cious Popular,” he said, dating himself. “And if you were up there you got a lot of traffic. For the next few days I was working fixing bugs trying to get it to load faster. It was fucking great.”

The site grew to become a place where tastemakers would go to hear new music, and, thus, a critical part of the music industry. Its distribution helped launch the careers of several internet-first artists like Passion Pit, Chiddy Bang, Neon Indian and Lana Del Rey, among others.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/304765114″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

In 2008, Billboard described the Hype Machine as “One of today’s most groundbreaking online music services … emerging as a juggernaut of growing influence.” In 2009, Volodkin was named one of Inc.’s 30 under 30 (in a post written by a young Nitasha Tiku, no less).

But the world moves on. Where Hype Machine was well-positioned in the new universe of music blogs, the industry has continued changing. People still write and follow music blogs, to be sure, but not as they once did, when Vampire Weekend went from unknown to indie kings off the strength of blog buzz.

In a 2014 feature about their album Modern Vampires of the City, Pitchfork writer Carrie Battan talked with Vampire Weekend frontman Ezra Koenig about how the industry has changed.

“We talk about how people discussed the internet six years ago, citing Vampire Weekend as an example of a band whose bloggy buzz bubble was probably doomed to burst. ‘Even the word blog sounds a little grandma-y,’ [Koenig] says. ‘This whole concept of buzz feels so dated. It’s really hard to even talk about the internet without seeming instantly corny.'”

Volodkin agrees the industry has changed. When blogs first appeared, the music writing world was closed off to young talent, he said. Hierarchies were in place. David Fricke, Peter Travers, those guys weren’t going anywhere. But the internet opened those worlds up. Young writers can write for Pitchfork now, or Buzzfeed, or a host of other places that didn’t exist, or didn’t exist in the same capacity in those days. The outlaws of the wild west of music blogs were cleaning up and getting jobs. The blogosphere was commoditizing.

“It definitely changed the type of blogs that are out there, it’s way more professional [now],” said Volodkin. “And that’s another thing I’m thinking about, too. If we don’t have blogs in the same way we did what are some other ways we can accommodate? But I’m also interested in finding a set of individuals. Maybe they do it on Twitter now. It’s part of where people hang out online.” (Here’s Hype Machine’s ever-churning “Most Popular Tracks on Twitter” list.)

But at the end of the day it's the individuals that matter. There remains something about real people interacting that has a je ne sais quoi property that engages us.

“It’s about building this connectedness,” Volodkin agrees. “When you’re looking at the charts, you know other people are looking at it, too and it’s this feedback loop. … Comparing that connectedness to Fresh Finds, which is a new music playlist Spotify has that’s built from data, its really good and I use it, but it’s disconnected from listeners. If you listen to Fresh Finds nothing happens. It’s just a playlist. And I think that’s not quite as much fun.”

So perhaps this is why the Hype Machine persists, all these years, all these epochs of internet history later. And maybe this is a lesson applicable to more than just this one website, to a larger world of technology that seems bent on delivering automated services. People crave other people. In an evolutionarily hardwired, down to the GACT level, being, to quote another late-aughts internet sensation, “a part of something bigger than yourself.” So we break off into communities where we can talk and share with other people interested in the same stuff. And if the product of music discovery built by an algorithm is pretty good, and maybe because of its distribution rules the market, that’s fine. But for people who self-identify as music lovers, early adopters, there can be little that matches the excitement of being in a community of others excited about the same thing. If machine learning can ever replicate that, then it may have finally won.

But it hasn’t.