For Mónica López-González, creating art and analyzing data aren’t on opposite sides of the brain. Instead, they’re part of the same project.

López-González is well-acquainted with the aesthetic, creative side. She’s a classically-trained pianist who studied at Johns Hopkins’ Peabody Conservatory. She also a photographer, playwright and filmmaker.

It’s in her work as a cognitive scientist, however, that art becomes data.

López-González uses that data to consider a question that could have implications for explaining how the brain works: “What’s happening in the brain while we create something new and different that’s artistic?”

Magicalness in cognitive terms means unexpected, surprising, spontaneous — and it's totally measurable.

To gather the data, López-González provided musical ensembles with a movie and a play — both of which she made. In both cases, the “entire score was improvised live in the moment,” López-González said.

The “data” from those performances will be on display over the next two months as part of an exhibition at the Maryland Art Place (MAP), Titled “On the Mind,” the show will be the first since renovations were completed at MAP’s first-floor gallery on the west side of downtown Baltimore. The contemporary art-focused organization moved from Power Plant Live! last year, marking a return to a space it occupied from 1986-2001.

The work that will be displayed at the show is also reflective of a return, of sorts. In the 1950s, scientists began using art-based research to study how the brain works. It fell out of vogue for decades as technological advances emerged at rapid-fire pace. Recently, however, there’s been a new recognition that studying the creative process can lead to a better understanding of cognitive processes.

In the four artists in On the Mind, there’s proof that the art world has an active place in this ongoing study, too.

Those looking for the way to build a bridge between the two worlds need look no further than López-González. As comfortable in the lab as she is behind the camera, she had a postdoctoral fellowship at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and is also on the faculty at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). By turn, her works of film and theatre come with a data analysis of the improvised musical scores.

To the 31-year-old, art represents a chance to get out of the lab, and experience the brain working in real-world scenarios.

“In the lab it’s full of controls,” she said. “If you start constraining it, are you really studying creativity? Creativity is all about something unexpected — that magicalness. Magicalness in cognitive terms means unexpected, surprising, spontaneous — and it’s totally measurable.”

To take those measurements, she divided her film into chapters that would reflect six universal emotions: happiness, sadness, surprise, fear, anger and disgust.

The improvised scores represent the data. López-González analyzes how various musical elements such as tempo, tone and rhythm play out in the presence of different emotions. She’s looking for similarities or differences between the emotions that could lead to a unified theory that would answer the question: “What type of information is the mind putting together to get to the product of improvisation?”

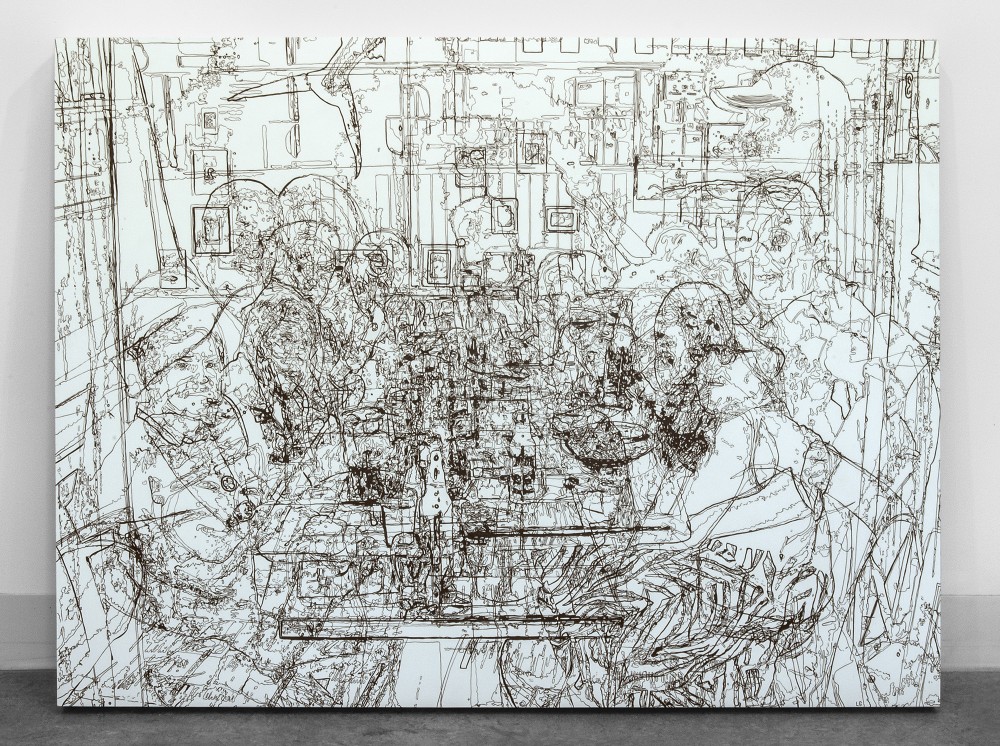

Even more implications for how the mind processes and uses art can be found in the work of two other artists. Lee Gainer’s acrylic paintings reveal varying interpretations of memories, and how they look when they appear on canvas.

In turn, Nancy Andrews’ work also looks at memory, albeit very painfully. The artist developed post-traumatic stress disorder after her stay in a post-operative ICU in 2006. During the dark hallucinations, it was art, including music from an iPod, that helped her to heal.

“A friend of hers brought [the iPod]. It helped get her out of this state she was in, and helped change her whole trajectory,” said MAP Executive Director Amy Cavanaugh Royce. “Music was a huge part of Nancy’s recovery, and also the artistic process.”

Now, Andrews is spreading the word about the effects of PTSD through the art she created to explore the effects of her experience. She’ll have drawings on display at the show. On Feb. 25, her film, On a Phantom Limb, will screen in conjunction with the exhibition at MICA.

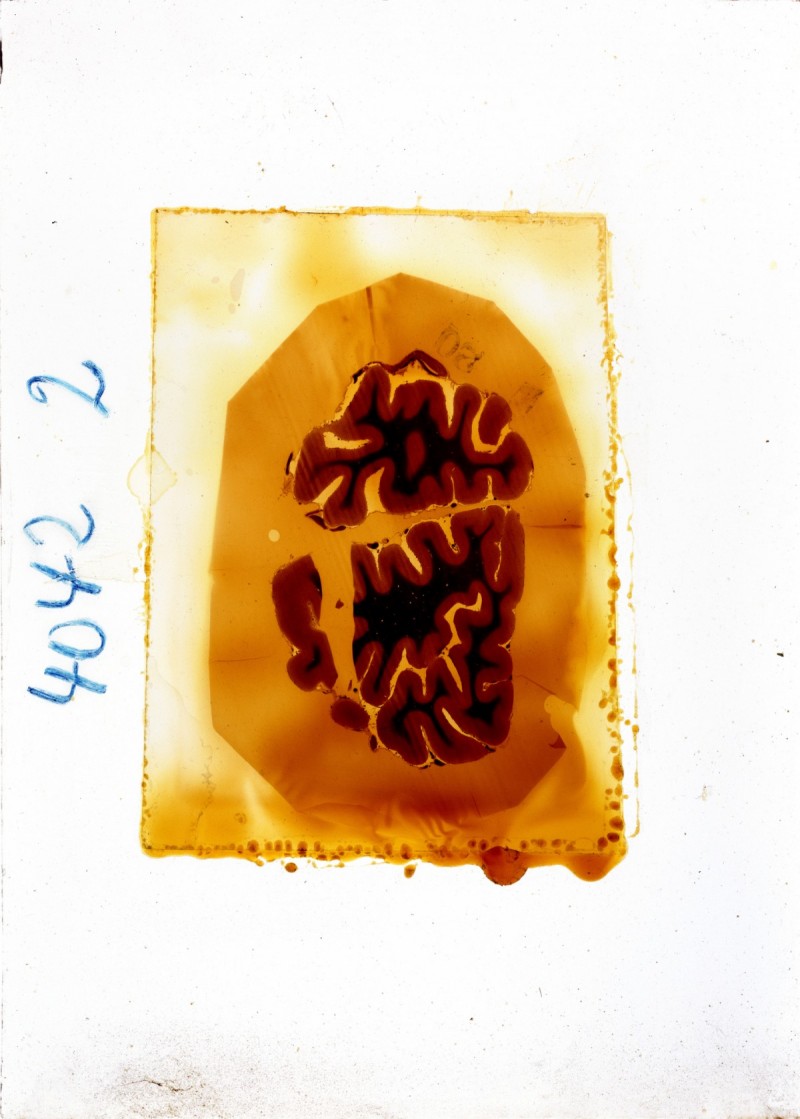

While the exhibition examines the brain from many sides, the work of each artist also nods to how little we know about the workings of the mind. Photograhper John Malis perhaps drives home the point most emphatically by showing depictions of the physical brain itself.

In photographing slides from a 100-year-old archive from St. Elizabeth’s psychiatric hospital in Washington, D.C., Malis found the limits to what you can tell about the brain just by looking at it.

“The people that he’s spoken with have said, ‘You really can’t even tell what was wrong with the person,’” Royce said. “Even with all this visual information that we have, there’s really no way to even explain what was wrong with them.”

The statement lead this reporter to blurt out that there was still so much about the brain that we don’t know.

“Gosh, we know nothing, really,” López-González said.

On the Mind runs from Jan. 22-March 14, at Maryland Art Place (218 W. Saratoga St., Baltimore). Weekly gallery hours are Tuesday-Saturday, 12-4 p.m.

Before you go...

Please consider supporting Technical.ly to keep our independent journalism strong. Unlike most business-focused media outlets, we don’t have a paywall. Instead, we count on your personal and organizational support.

Join our growing Slack community

Join 5,000 tech professionals and entrepreneurs in our community Slack today!

Entrepreneurship is changing, and so is the economic development behind it

Tech Hubs’ new $210M funding leaves Baltimore and Philly off the table

Here’s what to know before using AI to craft your brand’s social media posts