Let’s start with the hair, not because it’s anything to laugh at, but just because it’s hard to miss. Half of Karl Ekdahl’s head is shaved, while the other half of his silvery blond hair hangs past his shoulders and is swept to the left side of his face.

When you run your own business building synthesizers for the likes of musicians such as Dan Deacon, the proprieties of high-and-tight haircuts need not apply.

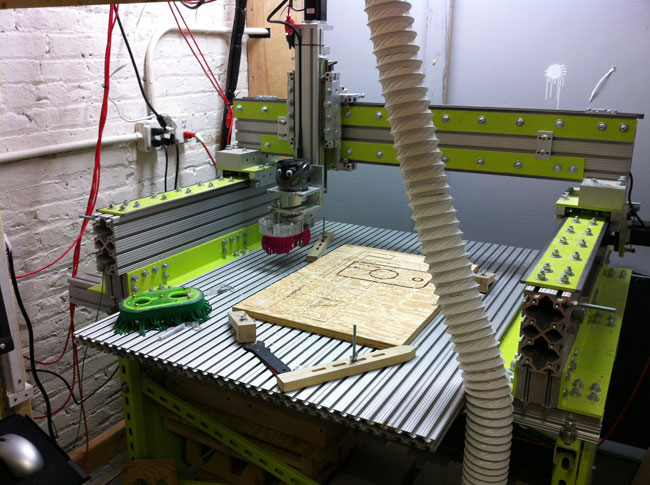

Then there’s the space, chaotically ordered — boxes stacked on a wooden set of shelves, sawdust sprinkled on the floor around the base of a CNC router — save for the workbench at which Ekdahl spends 10, or 12, or sometimes 14 hours at a time paying meticulous attention to a hand-drawn blueprint.

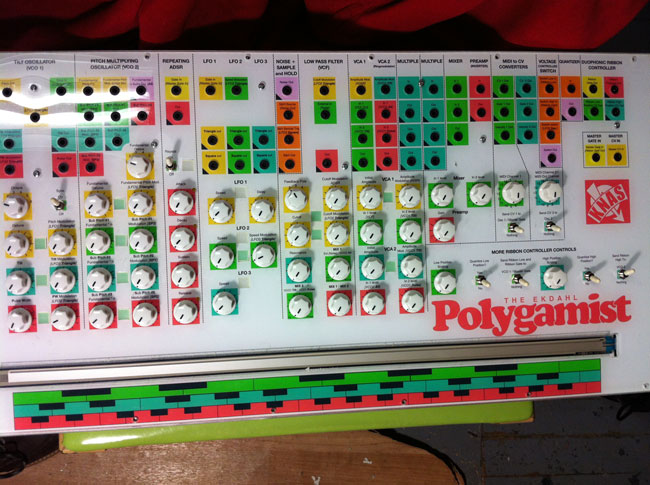

From a third-floor, walk-up workshop in West Baltimore, Ekdahl spends his days staring at blueprints while assembling a line of synthesizers he has spent several years designing. There’s the Moisturizer, which he has been making for four years, and the Polygamist, which took him three years working part-time and $5,000 just to finish the prototype. Basically a box about two feet in length, the Polygamist features 48 knobs, several switches and colored input boxes for hooking up the synthesizer to speakers.

“Once it’s nailed, you can build one of these fairly quickly,” he said on an afternoon in mid-December, picking up and pointing out individual elements of his Polygamist box while puffing an e-cigarette. “But sourcing all the parts, finding someone who can send you the parts.” His voice trails off. That’s the stuff that takes the most work. Ekdahl is now starting another run of Polygamist orders, and it’ll be another month or so until he has enough of the requisite parts to complete each synthesizer. Once the parts have arrived, it takes two days to build one machine.

But Ekdahl couldn’t have predicted he would be a man in his early thirties slinging down cups of coffee to fuel 14-hour days soldering wires to the circuit boards that power his synthesizers. Originally from Sweden, he moved to Baltimore seven years ago “on a whim,” he said.

In his early days in Charm City he was living in Hampden and working at The True Vine record shop, repairing instruments and “doing a little bit of circuit bending.” A friend approached him with an idea for a custom synth, and Ekdahl built one from scratch — that was the first version of his Moisturizer, which he released for sale officially in summer 2009.

“I thought I would sell 5. I’ve now sold about 700 of those,” Ekdahl said. “I had absolutely no education with electronics at all. I learned everything online.”

It was a rogue form of Montessori schooling. Ekdahl never attended to college, “basically failed high school,” and served as a computer programmer for the Swedish government for several years. But his knowledge of electronics came wholly from a mailing list run out of the Netherlands, SynthDIY, that he joined in 1996.

“Essentially, a bunch of old dudes on a mailing list. Lots of people who are on this mail list have been there as long as I have or even longer. Some of them worked with Moog,” said Ekdahl. Prescient training, since the Moog company was the outfit of Dr. Robert Moog, a pioneering manufacturer of analog synthesizers. When Ekdahl was 18, he built his first analog synthesizer, and never looked back.

And under the company name Knas, business in Baltimore has flourished. In addition to electro-artist Dan Deacon, the electronic band Matmos and other musicians at Baltimore’s annual High Zero Festival use Ekdahl’s synthesizers, which are shipped internationally and sold from three retail stores in the U.S. in addition to stores in Germany, France, Australia and Ekdahl’s native Sweden.

“Baltimore has, hands down, the best music and arts scene I have ever experienced,” he said. Although he arrived on impulse, that scene is the reason Ekdahl stuck around. “I’ve never experienced a city with so much creativity and so many creative people helping each other and getting together. My company would not exist at all without that scene.”

Listen to Technical.ly Baltimore’s electronic music playlist.

Depending on what a musician needs, Ekdahl’s synthesizers are fairly competitively priced. The Moisturizer runs for $400, but Ekdahl’s Polygamist costs $1,450, and he needs $700 up front to buy the parts to complete each order. (Although Ekdahl has a tiered pricing system for musicians on a limited budget.)

All the work is done in his studio on North Paca Street, several blocks from Lexington Market. Sometimes a friend or his girlfriend helps out, but it’s mainly Ekdahl toiling away at his workbench.

“Many companies hand out circuit boards and stuff to companies in China, but we make everything ourselves as far as we can,” said the 33-year-old. “This is my art. This isn’t just a business. So I can outsource things and I won’t really know how it’s made, or I can just give the money to one of my friends and have them build everything.”

It makes sense, then, that Ekdahl feels an exceptional kinship to a place more than 3,000 miles from home. In a way, the time he has invested in his art form is equal to the time that Baltimore has invested in him.

“The last couple of years I’ve pretty easily been able to sustain myself on this. I’m definitely not a rich guy,” he said. “But I survive. I survive on doing what I love. And nobody tells me what to do. So that’s kind of all I have.”

Before you go...

Please consider supporting Technical.ly to keep our independent journalism strong. Unlike most business-focused media outlets, we don’t have a paywall. Instead, we count on your personal and organizational support.

Join our growing Slack community

Join 5,000 tech professionals and entrepreneurs in our community Slack today!

The person charged in the UnitedHealthcare CEO shooting had a ton of tech connections

From rejection to innovation: How I built a tool to beat AI hiring algorithms at their own game

Where are the country’s most vibrant tech and startup communities?