On March 11, the novel coronavirus disease was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. Now that it’s October I’m mostly embracing the uncertainty and vast changes of the pandemic, as this is nearly the eighth month of following CDC guidelines and precautions for COVID-19.

Full transparency: I’ve spent days crying, being less than equipped for mere trips to the grocery store and even feeling undeserving of celebrating personal victories due to the state of the world. Other days have felt like a regular, blissful, sun-filled summer, with socially distanced trips to the beach, snowballs and patio dining experiences. To some extent, I’ve loosened up a bit with regard to anxieties around the pandemic, but it still governs the way I eat, shop, see friends and even the way my kids will learn this school year.

I’ve always been someone working on various projects that push me to solve complex human problems creatively. The pandemic, in some twisted way, has inspired me to expound on my knowledge and toolkit to do so. So, in April, after assessing my bandwidth, I made the decision to pursue my M.A in Social Design at Maryland Institute College of Art.

With support, wisdom, and letters of recommendation from close friends, colleagues, and believers like Michelle Geiss, Executive Director of Impact Hub Baltimore, Maggie Villegas, Executive Director of Baltimore Creatives Acceleration Network, and Jackie Downs who serves as the Arts Council Director for Baltimore Office of Promotion and The Arts, I was feeling very confident about my admissions to the program already.

Chris Harring, who serves as MICA’s Director of Graduate Admissions, helped me to submit an application to MICA cobbling all of my experiences together into a portfolio and I was invited for a virtual finalist interview for admissions on May 18. I met Center For Social Design faculty Thomas Gardner and director Mike Weikert in that interview, and I was very candid about my worries with entering MICA given the institution’s recent admittance of their racist past.

Both Gardner and Weikert were very reassuring and open about the Center for Social Design’s role in MICA forging ahead toward a better future with diversity, equity and inclusion in mind. They pointed in the direction of Black women alum of the program like Kayla Ingram, Kadija Hart and Denise Shanti, some of which I was able to connect with in order to get a first hand account of what it’s like to be a Black woman at MICA. Gardner and Weikert’s graceful responses and flexibility in being reverse interviewed on their policies surrounding race during my finalist interview let me know I was aiming for the right program. I instantly loved them and hoped they felt the same. On May 22, Harring, from admissions, sent an email saying, “We (MICA) are pleased to offer you admission to the Social Design MA beginning fall 2020. Congratulations on being selected to join this outstanding community of artists, designers, critics, curators, and educators.”

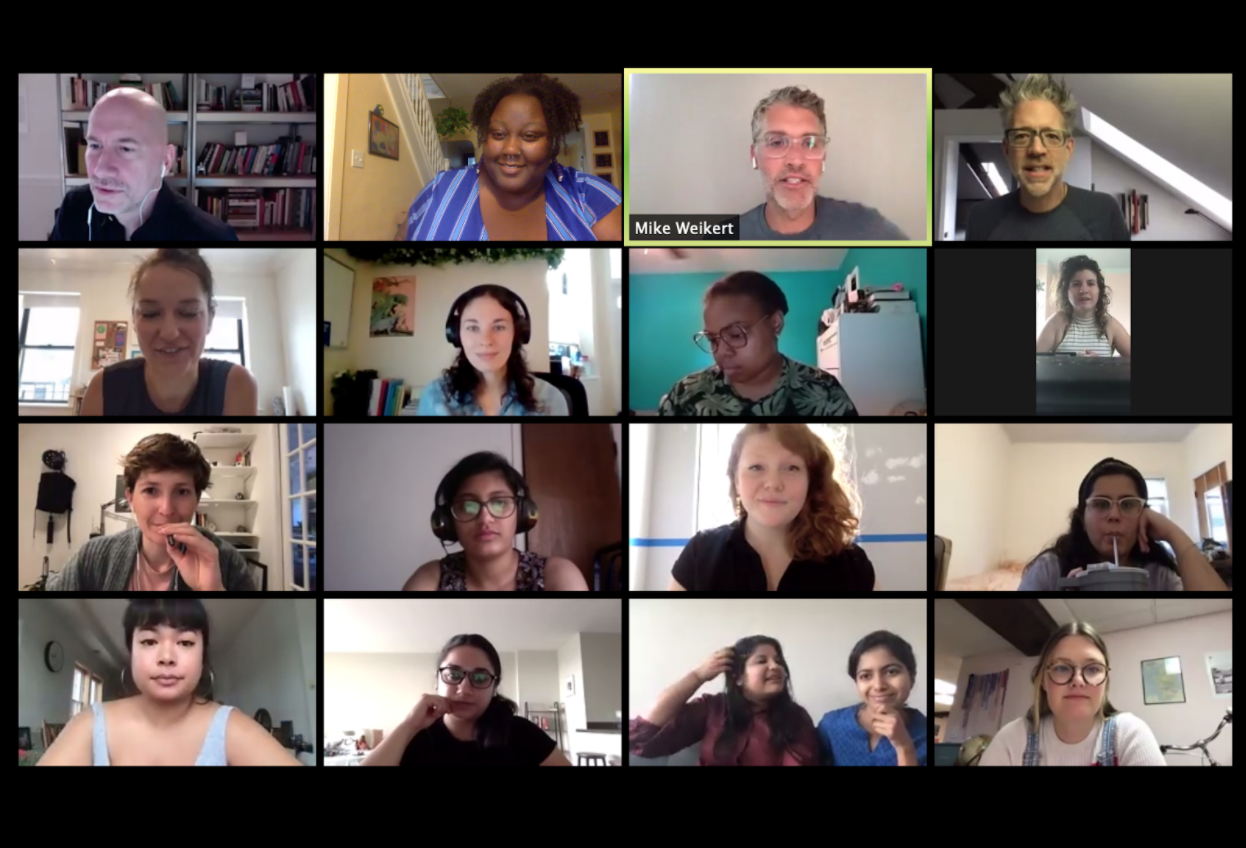

I was and am still ecstatic about my admittance to MICA (you can see that in this snapshot of the first day of class)!

On July 6, MICA announced a plan to reopen the campus for in-person learning. But in an update on August 4, MICA President Samuel Hoi decided that our Fall 2020 semester would be delivered online, and the physical campus would remain closed. (That’s why we were on Zoom in the above photo).

This was kind of a bummer. Just days later, on July 20, Baltimore City Public Schools announced that students would return to classes online for the start of the 2020-2021 academic year. All of those decisions felt like the safest bet to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus disease, but it still sucked that my kids wouldn’t be reunited with old friends or be able to meet new friends or teachers in a classroom setting. I quickly deduced that I’d likely not be making the acquaintance of Weikert, Gardner, or my new peers like Damella, Kalyani, Bryn Isaac, and Asheeta in my graduate program for social design at MICA.

Because this was and is all so new, I don’t necessarily know exactly what I’m doing — and am okay admitting that. I spoke about that piece of not knowing with Becky Slogeris, a faculty member for the Center for Social Design at MICA who leads our practice-based studio every week. In our practice-based studio, we created a set of team agreements/community norms, which include things like being flexible, curious and, for my contribution, “Be ok with not knowing.” That phrase helps bring some ease to what have been difficult hurdles.

What is also bringing ease is coming to know a set of methods to help me chart this new territory of online learning at home, both for myself and the kiddos. In my seminars with Weikert, Gardner, and guest speakers, we have been absorbing aspects of human-centered design. It is a practical, repeatable approach to arriving at innovative solutions. This practice has principles and methods that we as designers use to arrive at a solution. I’ve paired the teachings from this semester at the Center for Social Design and common sense and am inviting you to follow along and be a part of my design team to help me better embrace online learning this year. First, we must acknowledge our problem statement, which by the way can be iterative. A problem statement is a concise description of an issue to be addressed or a condition to be improved upon. In this instance the problem statement could be:

Example Problem Statement: Typically school would be administered in-person but the pandemic has thwarted that. Parents and Children are both at home and trying to cope through a stressful learning experience together.

After brainstorming a bit (feel free to do so alongside me at home), I’ve come up with a positive goal statement for us using a format taught to my class by Anne Marie Spitz of Public Design Bureau, who has led every stage of user-centered research and design, with an emphasis on creating new programs, strategies, and digital and analog tools. During the human centered design process you will want to come up with a clear positive goal statement that guides you or your group’s primary research. The format for that statement is as follows,“We want (people) to (behavior)”. Coming up with a positive goal statement could take a few tries and just like your problem statement it might be iterative but it’s important to consider what you’re motivated by, what could happen if you solve the problem or who you could access in order to work toward a solution. A positive goal statement is inspiration for how you might begin to solve your problem statement.

Example Positive Goal Statement: We want parents and children following COVID-19 precautions to find alternative workspaces to home.

It’s important that we both understand the four fundamental principles of human-centered design. You can read more about these principles and how to apply them here.

- Understand and Address the Core Problems

- Be People-Centered

- Use an Activity-Centered Systems Approach

- Use Rapid Iterations of Prototyping and Testing

In human-centered design, there are three methods that help designers arrive closer to a solution for their problem statement by exploring ways to approach the positive goal statement. These methods are a step-by-step guide to unleashing your creativity, putting audience (in this case myself and my children) you may be serving as a designer at the center of your design process to come up with new answers to difficult problems.

Inspiration

This is an essential phase, where I as a designer will learn to understand and empathize with the people and communities that I’m designing for by observing their lives and situations, and listening to their desires, fears and questions about a specific project.

The narrative of my experience with the past few months gave you a window into listening to my desires and fears and you are likely feeling inspired or empathetic toward myself and my children as we approach week 7 out of 16 in my virtual learning experience. See, we make a good team already.

I’ve been immersed in my own user journey and observant alongside my graduate-level peers and my 1st and 3rd grade children as we face both the challenges and delights of trying to learn at home. There’s apparently no better way to understand the people you’re designing for than by immersing yourself in their lives and communities. Immersion is just one method of many. So be sure to explore the IDEO design-kit if you plan to apply this to your own solutions at home.

While my family might be tired, irritable with one another, and ready to go back to in-person engagement because of feeling disconnected during virtual learning, those are only the symptoms of why virtual learning is hard with both parent and student at home which brings us back to the problem statement. I took the liberty of using post-its to outline some of the fundamental issues at hand from my point of view:

Ideation

This is the idea-generating phase that involves lots of research and collaboration. It’s where we as designers learn to evaluate ideas, as well as test, consolidate, and refine our solutions.

Together, we can now push forward toward a solution by evaluating our theory of change. Developing a theory of change is a good way to reflect on how each piece of your solution works together to drive towards the desired outcome. The first step in creating the theory of change is to identify shifts we’d like to create, for example:

From Parent not having alternative school from home options → To Parent knowing an alternative space exists

Rapid Prototyping

We could also use rapid prototyping which for human centered designers is an incredibly effective way to learn through quickly bringing ideas from the ideation phase to fruition. I took my idea to have an alternative school from home option for a spin for the first time on September 28 by jetting outside to get away from home in the hopes of getting fresh air. I was successful in getting fresh air near the Washington monument here in Baltimore, but I didn’t take into account that there wouldn’t be Wi-Fi. Alas, I do have a phone hotspot! But neither my laptop nor phone were charged, so I only spent about the 15 minutes it took me to snap this photo outdoors with my selfie stick. Then, I had to get back into my car for the remainder of about a 30-minute class to charge my phone and simultaneously drive home. I also realized that this still left the matter of food, noise pollution, and the kids and their learning unsolved. There were definitely a few pitfalls with this rapid prototype. Luckily, design in this context is iterative.

Implementation

This phase is all about the big picture, focusing on the logistics of bringing a solution to life and figuring out the best way for it to have the maximum impact. Just as I said before, I kept iterating and will continue to. Anne Marie Spitz, who I mentioned before, encouraged us around synthesizing after brainstorming our concept, and making sure we narrow and sort themes when coming up with how we might solve a problem. This is something I probably could’ve done better in this process, that’s okay! I realized that what I’ve outlined in my positive goal statement very well may be two different issues and that I may need to separate the parent (myself) from my children, in my positive goal statement. It’s okay not to get things right on the first try.

In class, we’ve talked about how human-centered design might be harmful and the concern is that the focus upon an individual or group might improve things for them at the cost of making it worse for others. In this instance of trying to figure out how to best manage schooling from home, we saw that. When I left home, the children lacked the parental support that they might need during the school day. My mom or their Grandma may have a different skill set or patience level for virtual learning. That’s another problem statement in and of itself. By separating the issue, the positive goal statement changes to:

New Positive Goal Statement: We want parents following COVID-19 precautions to find breaks from their children and at-home school + workspaces. (Or you take a crack at it).

I’ve since gone back outside, but this time I prepared by charging all my devices the night before, and went to an outdoor cafe space in Fells Point called Baby’s on Fire (they have delicious vegan brownies). I was able to support my mom at home with my children by video chatting with them to check-in on breaks. I spent hours out there as opposed to that first rapid prototype where I only spent 15 minutes.

Using human-centered design to embrace online learning is something I’m going to continue to expound on in the coming weeks and months. I’m going to continue to gather feedback as I move into live prototyping and piloting. I’d love to hear from you if you’re interested in being a part of my theoretical design process! E-mail me at adavis05@mica.edu or alanahnichole@gmail.com.