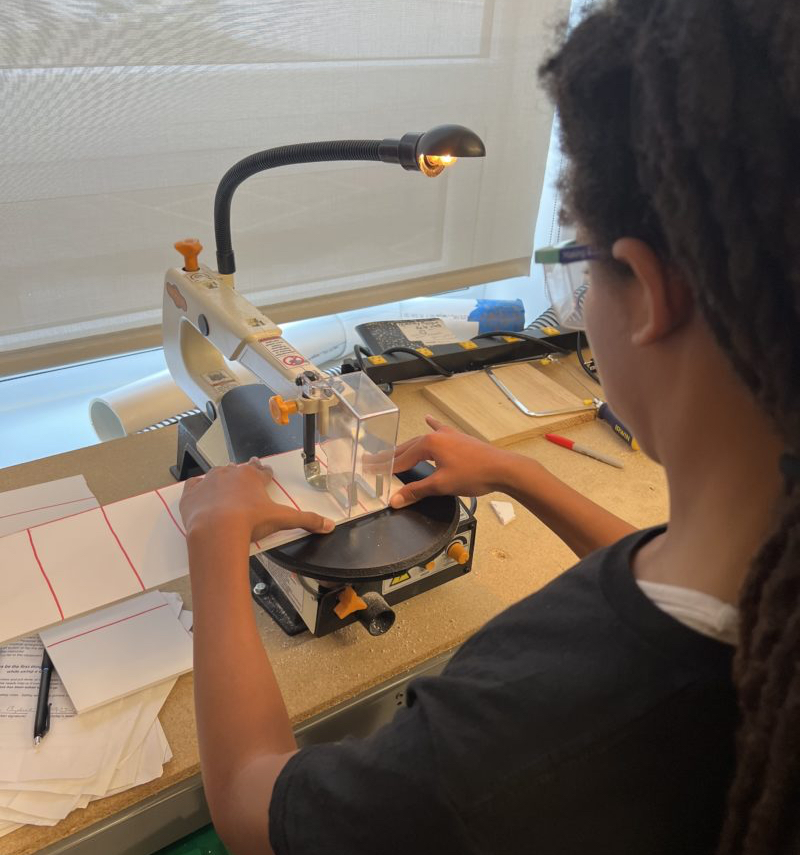

After SLA moved buildings, Kamal was able to custom design a three-room shop full of high-tech equipment, including a 3D printer, laser cutter and water cutter. The shop supports the Fairmount high school’s engineering career and technical education program as well as its after-school robotics program.

Most of the equipment in the new shop was funded by outside companies that he formed partnerships with, including a $100,000 grant from State Farm and support from businesses including Comcast and Boeing.

“Many corporations are interested in supporting STEM efforts in the city of Philadelphia,” Kamal said of science, technology, engineering and mathematics programs. “Tapping into that goodwill is, I think, an important piece of being successful and doing something like what I’m doing here.”

Kamal is one of many teachers in the School District of Philadelphia who are reaping the benefits of partnerships with outside companies. But on the other end of those relationships are business leaders who need to keep in mind certain considerations to make the relationships truly, mutually beneficial. It’s not as simple as donating some money and taking a picture with the students — though the money is always helpful.

Anatomy of a partnership

Before he was a pre-engineering teacher at SLA Middle School, Michael Franklin taught at Chester A. Arthur Elementary, where he partnered with the American Society of Civil Engineers to start a civil engineering club. That’s how he first connected with Center City-headquartered engineering firm Pennoni.

Four years ago, while at SLA, he met with the firm’s president and pitched the idea of a partnership to expose more students to engineering. Pennoni agreed to donate $17,000 over the course of five years. Franklin said having a long-term relationship with Pennoni is helpful because he doesn’t need to look for new funding every year.

“As engineers, we appreciate SLA’s focus on science, technology, engineering and mathematics,” David DeLizza, president and CEO of Pennoni, told Technical.ly. “These are all tools that we use in our everyday work. STEM education for our youth is vital to the strength of our infrastructure, the health of the public and the environment, and to the future of our world. As an engineering firm headquartered in Philadelphia, it is our responsibility to assist our local educators in cultivating the next generation of STEM leaders.”

Pre-pandemic, Pennoni engineers went into the school to conduct “mini courses” with the students. The Chester partnership with American Society of Civil Engineers also brought engineers to the school to help students with projects every week.

“Another piece is being able to leverage the institutional knowledge that they have,” Franklin said. “Having engineers come in and interact with my students was definitely something that very few of them — the students — had experience with.”

As this deal is approaching its end, the educator is in talks with Pennoni to extend it.

The benefit of flexibility

Franklin said one of the biggest benefits these partnerships have given him is flexibility: He can use the money for whatever he needs when he needs it. He said one-off grants are fine, especially if a teacher is looking to just do one project, but there can be stipulations around what the money can be used for, and then the teacher would have to go out and look for more funding after that.

“The ability to have that security of knowing that there’s funding for multiple years really does change what you’re able to do in the classroom with the students,” Franklin said.

Likewise, Kamal said he’s happy to accept a one-time grant with a large influx of funds, but the most valuable relationships are longer term, as with companies like Braskem and Axalta or the US Navy —partners that will stick around for five or 10 years.

They “want to be involved in STEM education,” he said. “They want their employees to get involved in supporting this kind of work that we’re doing in the city.”

John Kamal stands in front of his engineering shop. (Photo by Sarah Huffman)

Funding and beyond

Kamal said some of those relationships started because he worked in the industry before becoming a teacher nine years ago. Braskem, the Center City plastics maker, was looking for an opportunity to partner with a school, and their mission aligned with the mission at SLA. They have been partners for eight years. Through this long-term relationship, Braskem serves as a sponsor for the engineering program, but its leaders have also asked how to do more.

Case in point: Every SLA student has to do a capstone project before graduating high school, and they are often restricted by how much money they have to use, or they spend more time fundraising than on the actual project.

Stacy Torpey, communications director at Braskem, said the company wants to support programs aligned with its purpose and mission. So every year, the seniors go to Braskem to kick off the capstone accelerator program. Braskem hosts a series of workshops, provides mentors to the students, and runs a pitch day for students to solicit funding for their projects.

SLA High School students at 2022 the capstone accelerator kickoff meeting. (Courtesy photo)

The company launched its capstone accelerator program in 2017. Kamal said Braskem has funded nearly every student pitch they’ve received in the last few years.

“We felt there was an opportunity to engage even further with the students and help their projects come to fruition,” Torpey said. “We knew the students were paying out of their own pockets to fund their projects and many families aren’t in the position to do so. We felt we could step in to help, so we did, and it’s been a great journey.”

Braskem invites also students to shadow its employees to expose them to engineering, offers internships and keeps in touch until they graduate college since they might be potential hires, Kamal said.

“Forward-thinking companies like Braskem are thinking long term,” he said. “In addition to me doing good in the city of Philadelphia, how could this possibly benefit our companies six years from now?”

Some students from SLA have gone on to intern with Braskem in college. Torpey said the company will “always leave the door open to them.”

Advice for companies looking to partner with schools

For biz leaders looking to get involved, Kamal suggests looking for a program that is limited by funding, emailing the principal and asking, “How can we help your school?” Axalta, the Glen Mills coating company, did just that with SLA, resulting in a years-long relationship.

Look for ways to support beyond just funding, too. For example, the Navy helps support SLA’s after-school robotics program financially, but it also sends a mentor to coach students as they build robots.

Dr. Youngmoo Kim, professor and director of the Expressive and Creative Interaction Technologies (ExCITe) Center at Drexel University, said business professionals don’t always know how to teach a class, so they should take the time to get training before volunteering at a school.

Franklin said it’s important for companies to make their intentions known, so it’s easy for educators to find them. They should also listen to the needs of the teacher or program they are working with.

And it’s better to have a few-years-long partnership for sustainability than for a company to say they’ll fund certain projects or certain items; sometimes, Franklin doesn’t know what he needs until he needs it.

“I wouldn’t be able to do a lot of the things that I do with students right now without the partnership that we have,” he said. “I’m very lucky that I don’t have to go out of pocket for every single supply or tool or what have you, that I need. And if I had to, the program just would not be sustainable to the level that it’s at right now.”

The School District of Philadelphia building on North Broad Street. (Photo via Flickr user @its_our_city, used under a Creative Commons license)

Dan Miller-Uueda, STEAM curriculum specialist for the School District of Philadelphia, said he wants to change the mindset that the schools and teachers need saving. When he works with partners, he wants to make sure they are giving support to schools instead of proposing to come in and teach a lesson with the teacher off to the side.

Oftentimes, external partners will bring some new “toy” into the class, but teachers also need support for the work they’re currently doing or want to do, he said.

“When you just bring in something new, it’s something extra, something different that teachers have to do or that staff have to do,” Miller-Uueda said. “And then oftentimes when a partner goes away, it doesn’t continue because it was always something extra. But if you can build up capacity of teachers to do the things that they want to do or dream to do — were already doing — you are building capacity. So you’re building longevity.”

SLA Principal Chris Lehmann said the school’s partners at Braskem don’t come in with a preconceived notion of what they want to do. They are open and ask what resources they can bring to the table: “How do you work together to build something that’s really rich for everybody?” An effective partnership allows kids to see themselves in a role that fits into the wider world, he said.

It’s important for companies to ask good questions about how they can help, what needs the school has and what projects is the school already doing that they can help with, Lehmann said. Companies should have an open mind about what they can bring to the table to improve programs in the schools.

“Don’t be really paternalistic and assume that you’re going to swoop in and save some school,” he said. “Don’t think that schools want you to just do some preconceived program that doesn’t shape itself to the school that you’re working with.”

On the company side, Torpey said pursuing a school partnership is worth the effort.

“There is so much talent in Philadelphia and the youth is no exception,” she said. “They’re our future leaders, and we have the chance to help them define their path and show them the possibilities that are out there for them. And on the flip side, they inspire us to think more creatively and give us hope for how they’re going [to] change the world.”

_

This story represents ongoing reporting by Technical.ly to understand how to better prepare Philadelphia students for technology careers. If you have a relevant perspective to share, please do reach out to be included in future stories by emailing philly@technical.ly.

Sarah Huffman is a 2022-2024 corps member for Report for America, an initiative of The Groundtruth Project that pairs young journalists with local newsrooms. This position is supported by the Lenfest Institute for Journalism.Before you go...

Please consider supporting Technical.ly to keep our independent journalism strong. Unlike most business-focused media outlets, we don’t have a paywall. Instead, we count on your personal and organizational support.

3 ways to support our work:- Contribute to the Journalism Fund. Charitable giving ensures our information remains free and accessible for residents to discover workforce programs and entrepreneurship pathways. This includes philanthropic grants and individual tax-deductible donations from readers like you.

- Use our Preferred Partners. Our directory of vetted providers offers high-quality recommendations for services our readers need, and each referral supports our journalism.

- Use our services. If you need entrepreneurs and tech leaders to buy your services, are seeking technologists to hire or want more professionals to know about your ecosystem, Technical.ly has the biggest and most engaged audience in the mid-Atlantic. We help companies tell their stories and answer big questions to meet and serve our community.

Join our growing Slack community

Join 5,000 tech professionals and entrepreneurs in our community Slack today!