When Eunice LaFate was a little girl growing up in the Jamaican countryside, she found inspiration for her art in nature.

“My parents raised 10 children and we didn’t have wealth, but we had values around education,” she said. “I started looking around at the beauty of nature and capturing that using a stick of charcoal and a pencil on the wall of my house — not to the delight of my dad.”

In elementary school, teachers would have her paint the borders of the classrooms’ chalkboards with paintings of hibiscus and tropical flowers, along with the school’s motto: “Only the best is good enough.”

“Other people immigrate [to the U.S.] for economics reasons, but not me,” LaFate said, noting that she had a good teaching job back in Jamaica and was recognized for her artwork. For years, she took three weeks of her six-week vacation from teaching to visit siblings in New York. Then one year she decided to visit a schoolmate who lived in Wilmington instead. On the last day of her visit, her friend threw a dinner party, and one of the guests was Robert LaFate, who would become her husband of 31 years.

“The weirdest part about it was, 14 years before I met my husband, my father had a dream. At the time there was another teacher who was interested in me, but my parents didn’t like him. So my dad said the man you’re going to marry is in the United States — and described the man. He described my husband to a T.”

Robert passed in 2015 after a period of illness, during which time LaFate served as his caregiver. The same year, she opened LaFate Gallery on lower Market Street, with a section devoted to her late husband called “Heart of Caregiving: Rebounding from Grief.”

The gallery was, in a way, a necessity, as she had sold her house and moved into an apartment.

“The big elephant in the room was where was I going to put 22 years of art if I moved into an apartment,” she said. “I started fishing around to find a space to store the art and one place told me $2,600 a month, temperature controlled. I prayed about it again and had a vision to open the gallery.”

As it happened, Friere Charter School was getting ready to move out of its LOMA location just as she started looking for gallery space. One look at the space, and she knew it was the place. She started the lease process right away, using money she’d saved from selling art over the years.

“It was what I call divine providence,” she said.

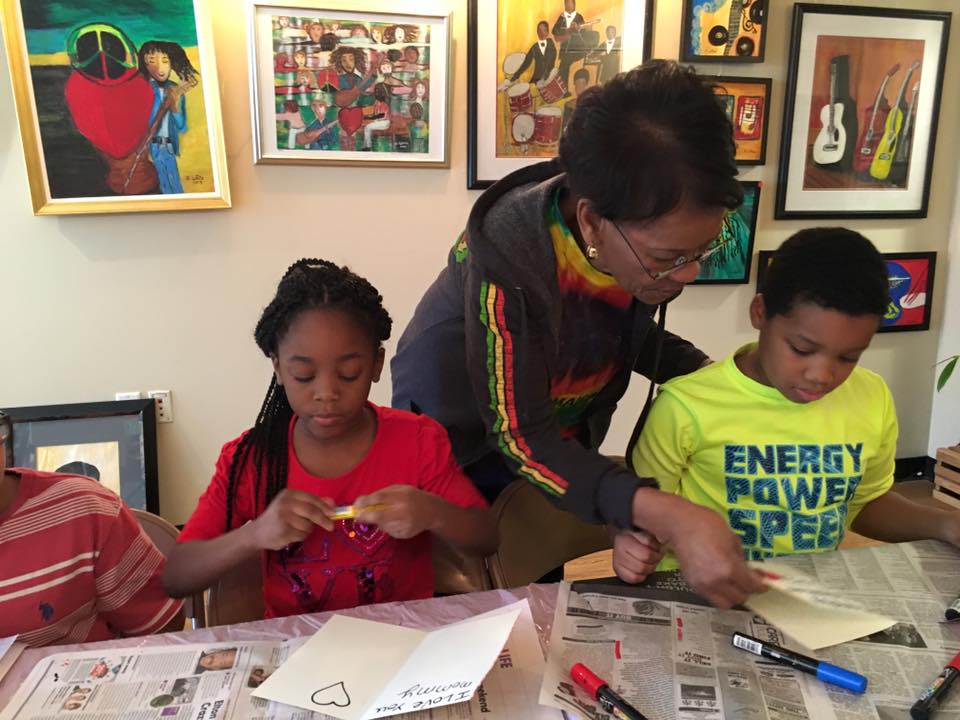

A lot happened between that first meeting with her husband in the early ’80s and the launch of her brick-and-mortar LaFate Gallery, which she calls her “Vision Center,” a place for the community, with its art classes for children and workshops such as “The Heart of Caregiving” and “The Art of Business.”

When she first moved to Wilmington in 1983, she took a job as a teacher at St. Peter Cathedral School. When she was pregnant with her son, who was born in 1984, she found that she couldn’t take the smell of paint. She put down her paintbrush and wouldn’t paint again for another eight years.

She got a corporate bank job. At the same time, she started volunteering for the Walnut Street YMCA.

“I was tapped to be captain for a fundraiser,” she said. “And I told my colleague that I don’t beg, where I’m from we don’t beg. She kept prodding me and I said, ‘OK give me time, let me pray about it. If I get a vision, I’ll help you raise the money.’ And that’s when I got the vision to start painting again after eight years. It was a vision which said if you have something tangible to offer people, you won’t have a problem raising the money.”

LaFate found that, as part of corporate America, her art had become a coping mechanism: “It was a means of coping with a culture that was defined by racism. We can use that word now. A culture shock defined by racism that I experienced while working in corporate.”

The biggest catalyst to her career as an artist came not long after, she said, when her artwork was displayed at a YMCA annual banquet, and Out & About magazine commissioned her to do a cover.

“A friend of mine saw the magazine and said, ‘Who’s your manager?'” LaFate, who saw her art as a hobby at the time, wasn’t thinking about growing her professional art career. “She said, ‘With this cover, you’re going to go places. I’ll go and pick up the [business] license for you.'”

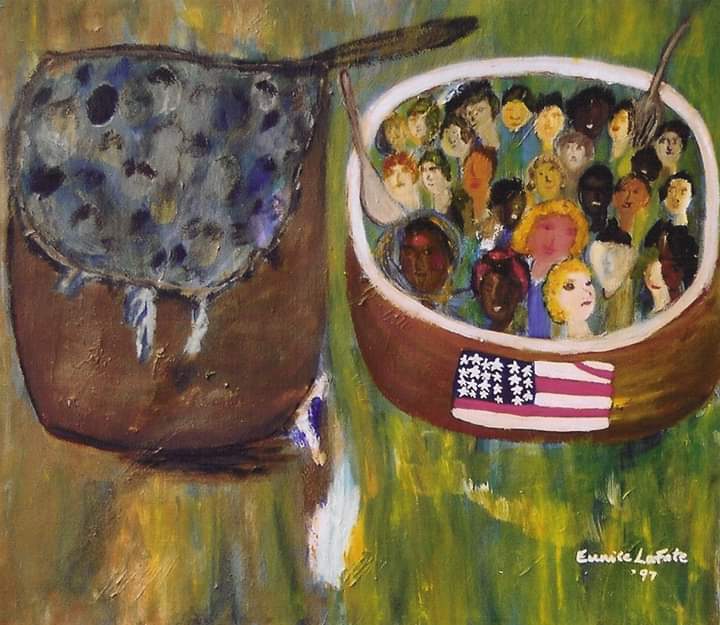

LaFate Gallery was officially born as a home-based sole proprietorship in 1993. She sold her art through big events and art exhibitions. In in 1998, her piece “Melting Pot vs. Salad Bowl” became her highest-priced piece; a print of it hangs in the President Bill Clinton Library in Little Rock (LaFate attended the opening), and it was used as the cover of a YWCA manual. In 2003, she was selected as a speaker on folk art with the Delaware Humanities Forum.

“I had a lot of exhibitions and shows during those years,” she said.

Back then, her studio was the kitchen of her East Side Wilmington home. In the summer she worked in her basement, which she opened up to her son and his friends, who she called her East Side Village Children, as a place to create art.

“Some of his friends were musicians, we would play music, rap, paint, and that kept them off the streets,” she said. The kids who stuck with it, including music producer Kevin Frazier, graduated from high school and went to college. There’s a Film Brothers short documentary about it, called “Arts as Prevention“:

In 2013, Blue Ball Barn on Alapocas Run State Park — the current home to the Delaware Folk Art Collection — held a 20 year retrospective of LaFate’s work.

But Blue Ball Barn, which purchased some of her art for its collection, was more of an exception than a rule when it came to local museums, organizations and companies buying her art for their collections.

Another, Phillips and Cohen Associates on the Riverfront, took down 18 pieces of their corporate art and replaced them with a display of 18 pieces of LaFate’s art, and they purchased a piece for the company’s collection.

“When I came to pick up my pieces, the employees were asking questions,” she said. “There’s a yearning to enjoy local art.”

It’s a yearning that’s not being fulfilled by many companies, she said.

“When I go to other cities I see the local art on the walls in the hallways of companies and corporations. Here in this city we have this ‘political correctness’ of what goes on the wall,” she said. “Our work is not valued to the extent that it’s being acquired. Black artists, we are in famine. We are starving. It’s not a price issue. There’s not diversity, equity and inclusion when it comes to collecting art from Black artists. I forced my way through because of my being forthright, I’ve been able to get some of my diversity in and around the city here and there, but it took me 20 years to break the mold, and I’m still working on it.”

In addition to the income disparity in the city, there’s also a bias in art collection, she said.

“So if you’re not a Brandywine [School] painter, then your art is not good enough to be on the wall in the boardrooms,” she said. “It took Edward Loper forever to get his work recognized. Now that he has passed his work is being recognized. I’ve tried to get my work in local museums and I’ve been rebuffed.”

For a city with a lot of pride in onetime resident Bob Marley, with the popular Peoples Festival and a park in his name, LaFate points out that her own work honoring Marley as a Jamaican-born Delaware artist is not on public display anywhere: “When you go to the museums, do they have an original Bob Marley painting? No. That’s the issue.”

Is there a solution?

“Well, for every solution you come up with they find a problem,” she said. “But let’s talk solutions: We need to establish an economic forum where we lay the issues out and seek some resolutions as to how we can improve — how we can be inclusive and how we can generate income in the Black community. African Americans are contributing a vast amount to the GDP. We should realize some of the wealth. That’s where economic justice comes into play.

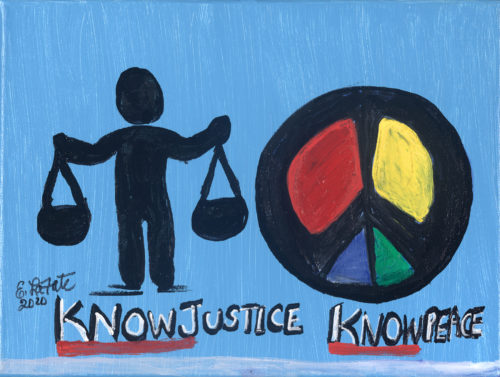

“When we talk about ‘No justice, no peace,’ I focus on K-N-O-W. After the disturbances I put my brush on canvas. My most recent series is KNOW justice KNOW peace.”

The LaFate Gallery Vision Center will hosts its fifth anniversary celebration with the theme “Rebounding From Grief to GROWTH” on Saturday, Sept. 26. Look for her details on the gallery’s events page soon.