The founder of Femly, a creator of tech-incorporating natural feminine hygiene products and bathroom dispenser systems (and our Baltimore winner for last year’s Tech Company of the Year award), has worked hard to garner capital investment from Baltimore investors — and come up short. She said she’s giving the city until August of 2023 before she pulls up stakes and moves the headquarters of her $1 million company to greener pastures.

“I tell people that Baltimore is a city where you almost have to be in some circles to have access to capital,” Long said. “You just do. You have to go with the flow. And I think a founder like myself — who says what she wants, is unapologetically herself — I’m questioning if I can have success here.”

Long added that someone in the investment ecosystem told her that she had turned over about every stone possible in Baltimore’s investment environment. It’s not that she’s been unsuccessful; she has won three different venture competitions, with investment totaling at least $100,000.

But now, she needs more investment, and it just hasn’t happened locally. She’s not the only one feeling frozen out.

On a group video call, four other Black Baltimore-area entrepreneurs — three women and one man — also expressed frustration with the regional investment environment. The thoughts they shared offer insight into a problem at the intersection of Baltimore’s long-standing capital availability issues and its even more historic legacy of discriminatory policies against the Black people that constitute most of its population.

Adulation without investment

“I think there is a racism issue, and I think there is sometimes an ageism issue, both on the younger side and the older side,” said 24-year-old CEO Adeola Ajani of Fem Equity, a software platform and app that provides education and real-time information on pay gaps affecting women and minorities.

“I’m young, but I have an advisory board of people ages 35 to 50,” she noted. “I think it is a goal post moving. We’re talking about high-level professionals building great things. I’m not really understanding the money issue.”

The millennial entrepreneur believes her business is definitely successful enough to have garnered more attention. Within nine months, a Fem Equity pilot program resulted in all 10 female participants receiving salary raises. They also leveraged government aid located by Fem Equity, which Ajani said resulted in $25,000 worth of student loan and consumer debt being canceled.

The company has raised tens of thousands of dollars in funding, including $45,000 in non-diluted funds. But Ajani believes the mechanisms local investors use to qualify startups for investments should be more straightforward and reliable.

She noted being encouraged by investment firms during Fem Equity’s search for capital, only to be told later that she didn’t qualify.

“It’s really a time-suck, because I am a high-growth startup,” Ajani said. “I am a tech startup. We’re trying to scale. We have a lot of things going on, and time is just something I can’t get back.”

Long agreed that adulation can be easy to acquire in the Baltimore tech startup landscape, but infusions of cash could be a lot harder to come by.

“Even if you look at my support here in the city, everyone claps, everyone supports, everyone shares posts, but no one writes checks,” she said.

Systemic barriers risk endemic flight

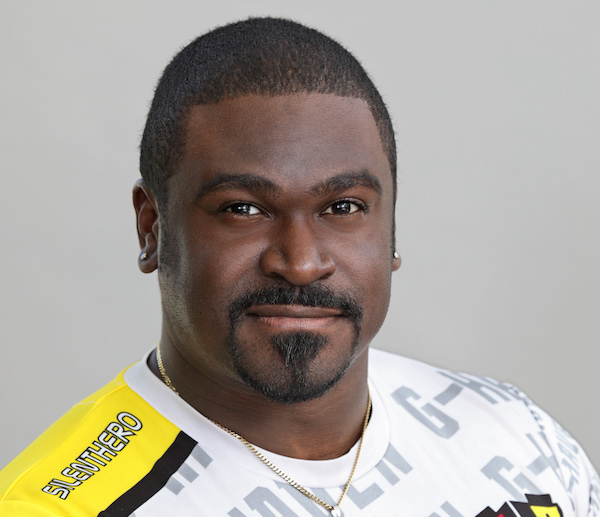

Dexter Carr Jr. is the founder and leader of Game4Good and the related 2022 RealLIST Startups honoree G-Haven eSports, which use esports as a vehicle to support social causes. He has also run into challenges when requesting local investment that he attributes to entrenched biases among investors.

“I definitely think it’s based on bias,” he said. “I definitely believe they choose the level of due diligence they do based on certain demographics.”

He noted that the level of vetting investors have required him to do before investing in Game4Good is out of proportion to the level of community support his platform has already received.

“I’ve lost a lot of opportunities for rapid growth because of the lack of belief, or the difficulty of trying to get money within the city,” he said. “Even though what I’m doing benefits the city, and we’re working with big organizations in the city who want to use my platform.”

Ana Rodney is the founder and CEO of MOMCares, an organization that helps women with high-risk pregnancies or NICU needs. She also thinks that the barriers to investment in local startups will cause founders to seek communities more willing to fund their work.

“The culture that that created was this really high bar before you get the go-ahead or the green light,” she said. “It permeates through all the institutions: funding, education, everything you could think of.”

Entrepreneur Tammira Lucas, who described her The Cube Cowork in Hamilton-Lauraville as the country’s largest Black woman-owned coworking space, noted that she’s not even looking to her hometown for funding The Cube’s expansion.

“Historically, the power in our city doesn’t look like me,” Lucas said. “There may be the face of what is seen to be power, but it’s not who actually holds the power.”

“That’s part of the problem,” she added. “I don’t know if that will ever be fixed. But that’s the reality and that’s the thing that people don’t say.”

For Long, her investment problem may have a solution she doesn’t want to take: moving Femly from Baltimore. She initially brought the company here from DC because she saw potential in the city. She had already gotten an opportunity for a $1 million grant outside of the area at the beginning of her journey with Charm City, she said – and didn’t take it.

Now, her clock is ticking.

“I’m not expecting it to be easy,” she said. “Any business is an uphill battle by far. But I didn’t anticipate some of the obstacles that I have come up against recently. And it’s sad.”

Are you experiencing similar challenges as a Black founder in Baltimore? Feel free to share your thoughts at baltimore@technical.ly.