We like stories of rags to riches, and believe our children ought to end up better off than we are. John Steinbeck famously wrote that socialism never took root in the United States because we’re all “temporarily embarrassed” millionaires.

Hence our unease with stories of inequality — which stormed into public consciousness after the Great Recession, as memorialized by the Occupy Wall Street movement. French economist Thomas Piketty’s landmark 2013 book “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” argued that inequality was worsening. His methodology informs many of the charts, facts and figures that tell us more income and wealth is concentrating in fewer hands.

The concern is widespread. Two-thirds of Americans see economic inequality as a major problem, rivaling climate change and gun violence, per 2020 Pew research. A majority of both Republicans and Democrats say businesses have a responsibility to reduce it — and believe worker upskilling is the best tool to do that.

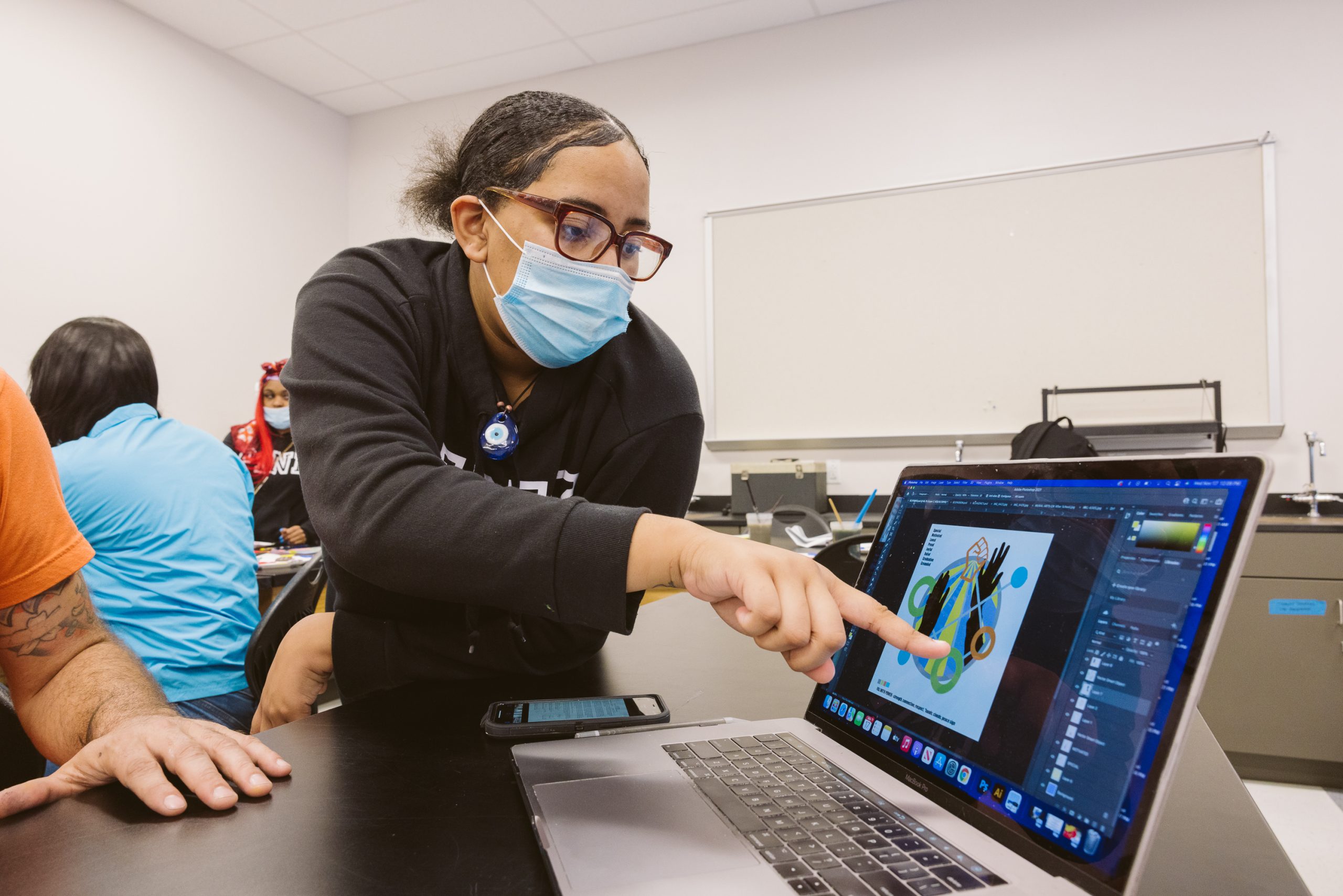

And so, in the late 2010s, local policymakers prized programs that made tech careers and entrepreneurship more accessible, especially for underrepresented Black and Hispanic residents. (Technical.ly detailed this transition last year in our report on inclusive entrepreneurship.)

If inequality is worsening, the strategy went, then we better close this gap by getting the right people into high-paying tech careers and wealth-generating business ownership.

But what if inequality isn’t the problem we think it is?

Is inequality really getting worse in the United States?

A paper by two respected economists accepted by the prestigious Journal of Political Economy last fall argued something very different: That income inequality is half as bad as Piketty put it.

Top incomes have grown less since 1980, they argued, and government transfers have boosted incomes at the lower level. This is now one of today’s hottest debates among economists.

Why is inequality so tricky to confirm? For one, a mess of related concepts get conflated. Income inequality compares how much people earn in a given year, whereas wealth inequality measures the combined net worth of people’s assets.

Both vary from year to year. As Technical.ly has reported, elite income earners see take-home pay spike (via bonuses and big profits) one year and sag the next. That volatility makes comparisons murkier than might be assumed.

Wealth is more durable than income, but has its own inconsistencies. Ask any entrepreneur about their private business’s valuation, or what a rich boss’s art collection is worth, and you’ll see why wealth tracking is tricky too. Plus, as much as a third of national income doesn’t appear on tax returns, including some employer-provided benefits, government welfare and the informal economy — i.e. cash payments and other exchanges. Researchers have to make assumptions, and how they do matters.

This new paper suggests the top 1% highest-earning Americans today take about 9% of all earnings, almost half as much as Piketty and team propose. And while Piketty argues the disparity is getting worse, the newer research says it’s been essentially flat.

The gaps between the highest and lowest earners and the people with the most and least wealth may still be too high. The bigger point: calculating inequality is not always clear cut.

It’s a less satisfying economic goal than we want it to be. What’s a better measure?

How is economic mobility different from inequality?

Economist Tyler Cowen has argued for years that inequality is less important than economic mobility — how likely is it that someone can earn more in their lifetime. Here, too, there is debate.

An influential 2016 paper argued the likelihood of an American to earn more than her parents has been declining since World War II, a point echoed by Brookings reporting. In contrast, Cowen has argued, mobility has remained essentially flat for decades. Framing the question differently, the conservative Cato Institute has argued the American Dream is alive and well: About 6% of the children born into the poorest households made it to among the richest as adults. (Note: The Cato analysis averaged a trio of studies comparing people born in the 1960s and 1970s, or Gen X. A lagging indicator by definition, it’s possible these numbers will shift for millennials or others that follow.)

The difference between these three again comes from the assumptions researchers have to make.

But whereas combating economic inequality is most associated with taking from the rich, economic mobility is characterized as boosting the poor. Given that a disproportionate share of poor Americans are Black or Hispanic, improving economic mobility disproportionately benefits people of color.

Helpfully, the last few years may have begun a new golden age for workers.

That’s because the American economy isn’t as bad as Americans say it is. Just 1 in 10 say we’re better off than a year ago, even though a great many demonstrably are.

Contrary to the aftertaste left by the pandemic, the 2020s has started off as a good decade for employees. Government stimulus was historically generous, and unemployment remains low. Suppressed immigration, declining fertility rates and the retiring Baby Boomers contribute to structural workforce shortages. Racial wealth and employment gaps have shrunk in recent years, including the unemployment and labor-force participation rates between Black and white Americans.

This is all especially true for lower wage work that requires in-person contact. Earnings are soaring for people in the building trades.

Will AI worsen inequality and mobility?

Many fear automation will wreck that good start. The buzziest technology of the moment is artificial intelligence, which is expected to transform work. Once again we’re being told the robots are coming for our jobs — worsening inequality as tech barons get richer and the rest of us fall further behind.

Maybe someday. To date, though, investments in AI are more aligned with worker gains.

Using US patent data from 1990 and 2018, Carnegie Mellon University’s Dean Alderucci and co-authors demonstrated that firms that invested in early AI grew revenue and employment far faster than peer companies.

Interestingly, more recent research seems to suggest AI will affect different roles in different ways and at different rates.

For some roles, ranging from call-center operators to software writing, AI appears to close the gap between the lowest and highest performers. In contrast, AI assistants appear to make high performing sellers even more effective than others — boosting some earnings above others.

It’s not entirely clear which is more common. More generally, technology investments do tend to benefit workers. Firms that added more robots between 2009 and 2020 boosted the wages of employees, who became more productive, according to a 2023 paper from MIT economist Daron Acemoglu. Moreover, Acemoglu’s research has shown that between 1980-2010, half of all employment growth came from entirely new jobs created by new technology.

This backs the argument that AI won’t replace workers, but rather workers who don’t use AI will be replaced by workers who do use AI.

What should local leaders do?

Many of the tactics policymakers cite to address inequality can be repurposed to support economic mobility.

For better or worse, the federal government is investing heavily into advanced manufacturing, research and development and workforce programs — whether to combat climate change or economically decouple from emerging rival China. A freshly announced $5 billion investment in semiconductor manufacturing from the White House is just the most recent.

Local economic development leaders are scrambling to attract funding like that, or the hotly contested federal Tech Hubs program. The workforce side of these programs can contribute to economic mobility.

Education and workforce development are vital. If you want to boost economic opportunity then get workers comfortable with robotics and AI, and the career pathways alongside them. Technical.ly’s recommendations for tech policy and supporting entrepreneurs are good places to start.

Social and cultural factors appear to help more than we might assume. Friendships across income levels boosts wages and benefits everyone, according to 2022 research on economic mobility. And amusingly enough, as a much heralded paper from last year demonstrated, “The most socio-economically diverse places in America are not public institutions, like schools and parks, but affordable, chain restaurants.”

That means any chance to encourage wealth integration — from mentorship programs, mixed-income housing or happy hours at Applebees — is a tool that benefits all of us.