A lot of that backlash has to do not just with the social media platform’s ubiquity, but its country of origin — and that worries people who see history repeating itself.

The global cultural phenomenon is owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, which has alarmed US lawmakers who fear alleged security concerns. Congress passed and President Joe Biden in April signed a bill that would ban the social media app nationwide unless it’s sold to a non-Chinese parent company.

California resident Cynthia Choi, 57, is not interested in defending tech companies. But in this bill, which was signed right before the US commemoration of Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, she sees an insidious undercurrent.

“The singling out of TikTok makes Asian Americans feel they have a target on their backs,” said Choi, who is co-executive director of the advocacy group Chinese for Affirmative Action.

“We do believe that there are legitimate national security and economic concerns,” she added. “What we are concerned about is the tone and manner in which these issues are brought up. How racist the Senate was in terms of their line of questioning of the TikTok CEO after he repeatedly said he was Singaporean.”

Cynthia Choi (Courtesy Stop AAPI Hate)

This is not the US government’s first attempt to ban TikTok. The Trump administration tried in 2020, alleging data transfers to the Chinese Communist Party. No evidence was found, and federal courts blocked the sanction.

Choi stressed that this action toward TikTok must be viewed within the broader context of foreign policy and immigration fears. Fearmongering by politicians opens the door, she said, for discriminatory policies and hate toward Asian Americans. She pointed to examples such as land bans and wording in the National Defense Authorization Act, which she said allows racial profiling and spying on Chinese Americans.

“We should be investigating all social media companies about privacy issues and bad state actors abusing platforms,” Choi said. “Not just TikTok.”

The ban’s legitimacy is being challenged with two lawsuits — one from TikTok itself and another from eight TikTok creators, both arguing that the law violates First Amendment rights.

As the legal battle plays out, many stakeholders share Choi’s concerns over what the law could mean for their communities, with some noting it reeks of the paranoia that anything Asian is a threat to the US.

A modern-day ‘red scare’

One of the criticisms of the TikTok ban is its potentially chilling impact on community and political engagement, particularly for Asian Americans.

Maria Javier, chief information officer for voting advocacy organization Public Wise, worries the legal and political battles will negatively affect Asian Americans who rely on social media for communication and advocacy.

“The voter effort was happening over WhatsApp, TikTok and Facebook,” Javier said. “Through research, our focus groups and some polling, we found that Asian Americans trust their local community more than official translated documents.”

A 37-year-old Filipino American living in New York, Javier believes TikTok is no more a security threat than any other platform, and that the current scrutiny reflects xenophobia and ongoing racism toward Asian peoples, as well as the censorship of certain perspectives.

“TikTok gives Gen Z a voice for strong causes,” she said, “like climate change and the war in Gaza.”

Maria Javier (Courtesy)

Kiera Spann, 23, shares Javier’s concerns about censorship. The Charlotte, North Carolina, resident is a plaintiff in the lawsuit against the government.

Spann, who uses TikTok to make civic engagement more accessible, sees the focus on the platform as a contemporary “red scare,” the anti-communist paranoia that led to US repression and persecution of suspected leftists in the 20th century.

“Unlike Meta, which censors political content and allows politicians to pay for ads, TikTok is driven by user-generated content and genuine public engagement,” Spann said.

“Politicians are shooting themselves in the foot if they get rid of TikTok,” she added. “That’s the number one social media site that young people are getting their news from.”

Rhetoric with real-world repercussions

These trepidations bear historical precedent. Will Schick, a mixed-race Korean American and US Marine Corps veteran, recognized the longstanding “fear of anything Asian.”

Schick, the 39-year-old director of programs and partnerships for the Asian American Journalists Association, drew parallels to past United States xenophobic policies, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Immigration Exclusion Acts.

“Part of the issue that Congress has with TikTok is its origin, being from Asia,” he said. “It’s about this nebulous tie to use this data in a way that would be unsafe for American citizens, but what I’m unclear about is how.”

Will Schick (Courtesy Asian American Journalists Association)

He urged the government to share information about threats to help the public understand the TikTok ban’s rationale.

“The US government may know something I don’t know,” Schick said. “As a US citizen, I would like to know what they know that I don’t. People deserve to know why.”

Harry Budisidharta, a 40-year-old attorney in Aurora, Colorado, similarly acknowledged the need for data privacy while criticizing the focus on TikTok alone.

Harry Budisidharta (Courtesy)

Arguing that the same issues exist for Facebook and Instagram, he called for a more comprehensive approach across all social media platforms — one that can hopefully avoid real harm for those perceived as Asian, like the spike in violence after the COVID-19 outbreak.

“Racist rhetoric leads to attacks based on appearance,” said Budisidharta, who emigrated from China to Indonesia before settling in the US. “We’ve seen anti-Japanese sentiment that led to the killing of Vincent Chin, even though he wasn’t Japanese. But his attacker didn’t ask that.”

‘Political football’ that could lead to a ‘dangerous precedent’

Talia Cadet, a 34-year-old content creator who works as chief digital officer at a DC lobbying firm, joined the lawsuit against the US government because she views freedom of expression as a universal right.

She also partly attributes the apprehension about TikTok to perceptions about its Chinese ownership.

“This ban was a political football,” Cadet said, “because other unrelated policy legislation, like the $95 billion of aid for Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, was included in the bill.”

Talia Cadet (Courtesy)

Christopher “Topher” Townsend of Philadelphia, Mississippi, sees his participation in the lawsuit as an extension of his commitment to defending American freedoms.

The US Air Force veteran, 33, believes the ban is “a dangerous precedent for freedom of expression.” He pointed to hypocrisy in the US government’s fears that the platform allows Chinese subversion.

“If all social media has to be controlled by an American company, we’re looking at a communist point of view,” said Townsend. “That’s not free market capitalism.”

Christopher “Topher” Townsend (Courtesy)

A marketplace for Asian American entrepreneurs

TikTok’s ban and the attendant criticism involve not only the principles of free market economics and expression, but also its unique qualities.

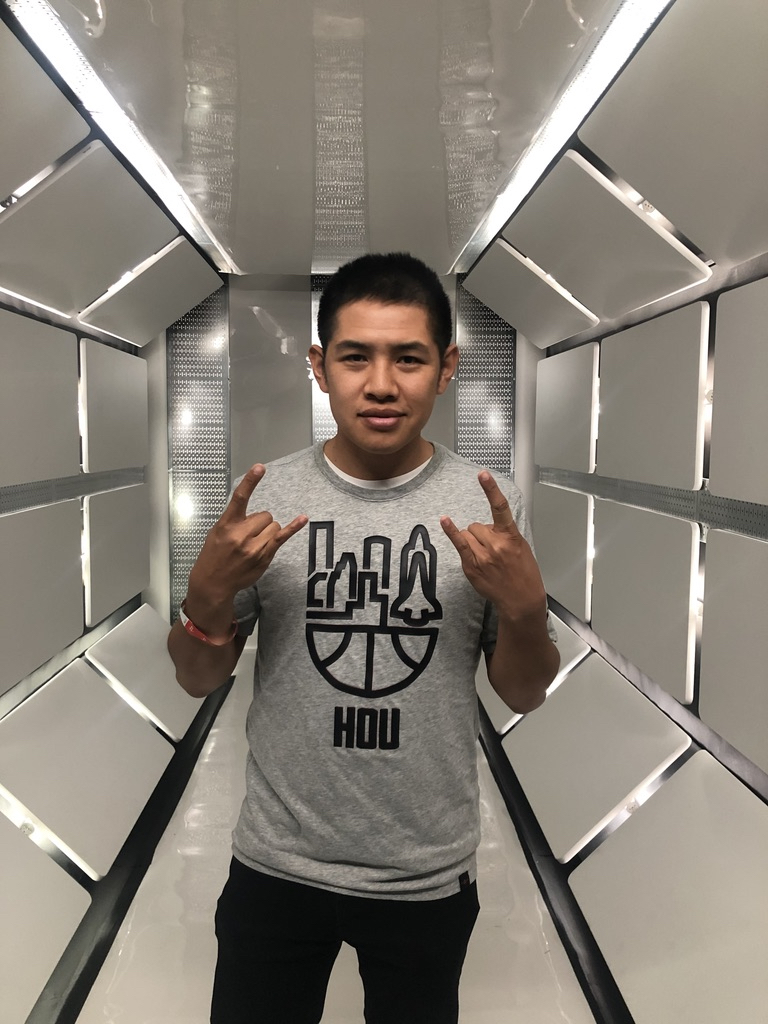

Matt Tape, a 40-year-old media integration specialist, praised TikTok for its authenticity. Sitting in front of a wall with basketball memorabilia, he recalled creating content for his hometown Houston Rockets.

Matt Tape (Courtesy)

“One of the first TikTok things we did was onboard the Houston dance team,” Tape said. “I followed them and then suddenly, my ‘For You’ page was full of dancers. It showed how accurate the algorithm is. TikTok’s ‘For You‘ page was its secret sauce.”

Tape, who is Chinese American, said this and other features appealed to many seeking a safe space from anti-Asian sentiments.

Vietnamese American entrepreneur Paul Tran feels TikTok provides an accepting community for fellow Asian American founders. The creator of the skincare company Love & Pebble attributed 90% of his skincare brand’s sales to the platform and its intimacy.

“There’s a huge human element that politicians don’t understand,” said Tran, 43.

Paul Tran. (Courtesy)

Matthew Kim, a New Jersey native of Filipino and Korean descent, agreed that a TikTok ban would hurt small businesses. The marketer noted that while Facebook, Instagram and YouTube are trying to replicate TikTok’s shopping capabilities, they lack TikTok’s community aspect.

Kim was especially annoyed by Sen. Tom Cotton’s questioning of TikTok CEO Shou Chew’s nationality and alleged affiliation with the Chinese Communist Party. The 30-year-old also highlighted the hypocrisy of politicians banning TikTok while promoting their campaigns on the platform.

“Do a Google search — you know, Google, a US company,” Kim quipped. “You’ll see that Chew is Singaporean.”

Despite the news of TikTok layoffs, Kim doesn’t see the platform declining: “It has over a billion users.”

Fighting anti-Asian scapegoating

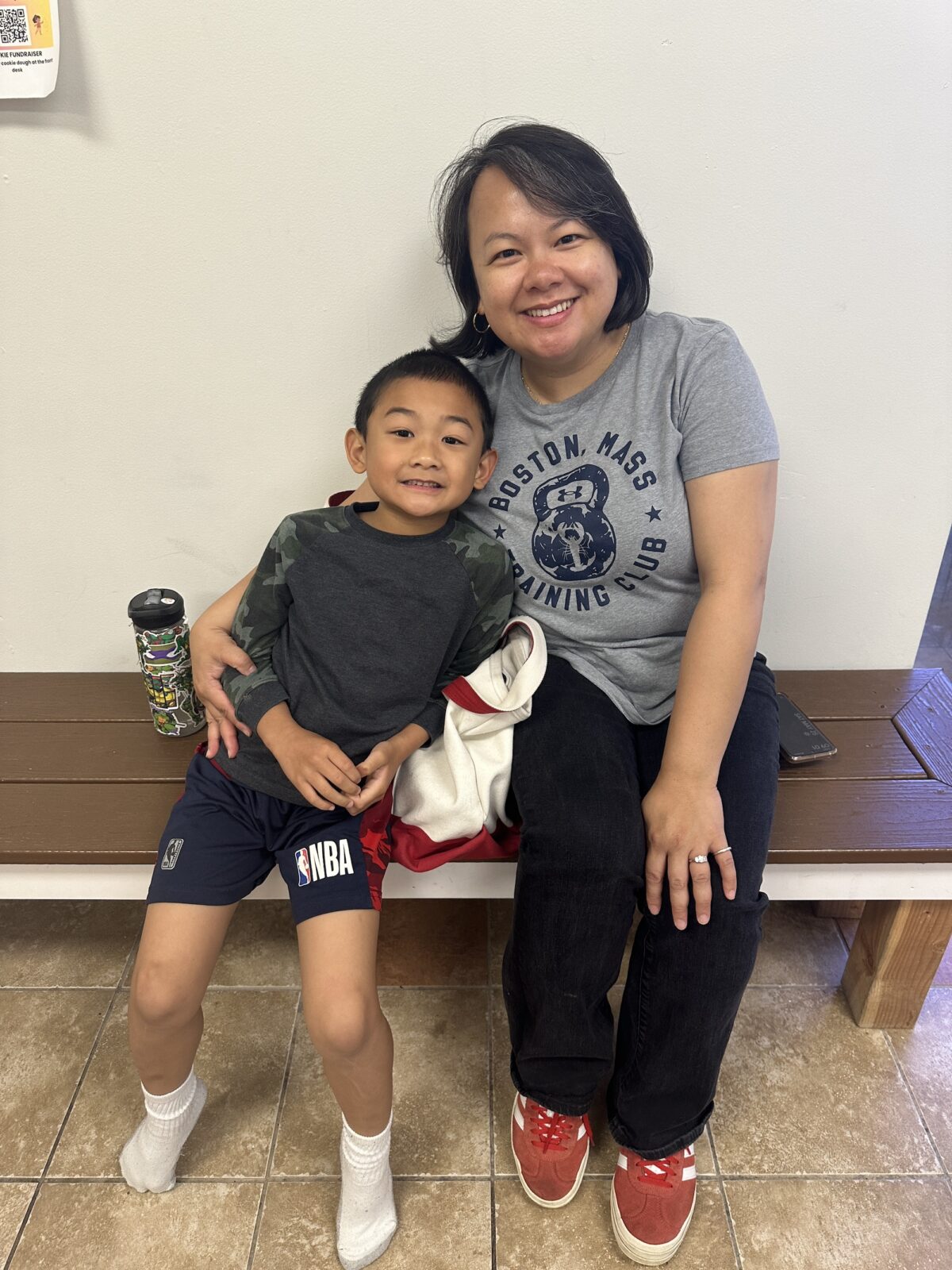

Mercyanne Publico, a Chinese-Filipino American from Chelmsford, Massachusetts, shared Kim’s optimism and frustration. She found irony in President Biden contributing to TikTok’s prominence despite trying to ban the app, as his campaign is using it to support his re-election. Challenger Donald Trump also recently joined TikTok to connect with voters.

“It’s two-faced,” Publico said. “It’s contradictory to the message they’re sending that TikTok is not safe.”

Matthew Kim with his father, Woody. (Courtesy)

Publico, 43, who leads global regulatory affairs at Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, proposes a strategic plan for TikTok to flourish despite the intense scrutiny from public officials. She drew parallels to her field, in which she balances benefits and risks.

“Patients are protected by informed consent. There are disclaimers they need to review and click on before we move on to the clinical studies,” she said. “There’s an investigator and an ethics review board. We need to collect private data, but we only have access to it as long as the study runs. Then after that, we don’t have access to their data anymore.”

Publico suggested the government require all social media platforms to adopt a similar methodology around data collection.

“This way, they’re not discriminating against TikTok,” she reasoned. “This way, they’re not discriminating against one group of people — Chinese people.”

Recalling a personal incident at McDonald’s where another customer made racist remarks toward her, Publico reiterated her resolve against discrimination.

Mercyanne Publico with her son, Aidan.

“I have a very kind personality, but do not cross me because I don’t let anyone disrespect me,” she said.

Similarly, Choi, also the cofounder of the Stop AAPI Hate coalition, highlighted the importance of validating Asian American experiences. Her organization leverages social media to educate the public and push for change. She pointed toward its Stop The Blame campaign, which seeks to hold officials accountable and counter these racist narratives.

For Choi, the TikTok ban controversy represents a key galvanizing moment for Asian Americans, highlighting underlying issues of racism and xenophobia. Social media platforms like TikTok are not just tools for entertainment — they are crucial for democracy.

“Our call to action is to call out when political leaders cross the line with fearmongering tactics and disinformation that ends up harming our community,” Choi said. “We want Asians, not just Chinese, to also speak out, because this is an issue that affects all of us.”

Before you go...

Please consider supporting Technical.ly to keep our independent journalism strong. Unlike most business-focused media outlets, we don’t have a paywall. Instead, we count on your personal and organizational support.

3 ways to support our work:- Contribute to the Journalism Fund. Charitable giving ensures our information remains free and accessible for residents to discover workforce programs and entrepreneurship pathways. This includes philanthropic grants and individual tax-deductible donations from readers like you.

- Use our Preferred Partners. Our directory of vetted providers offers high-quality recommendations for services our readers need, and each referral supports our journalism.

- Use our services. If you need entrepreneurs and tech leaders to buy your services, are seeking technologists to hire or want more professionals to know about your ecosystem, Technical.ly has the biggest and most engaged audience in the mid-Atlantic. We help companies tell their stories and answer big questions to meet and serve our community.

Join our growing Slack community

Join 5,000 tech professionals and entrepreneurs in our community Slack today!