The City of Philadelphia had a full week of citywide curfews, ending Sunday. A rep from Mayor Jim Kenney says: “The City is hopeful that curfews will no longer be needed in the very near future.”

To confirm your suspicions: This is not normal.

In a week of emails, conversations and outreach, this reporter hasn’t found a citywide curfew set by the City of Philadelphia since 1964, following the historic Columbia Avenue Riots — which marked a damning turning point in the city’s history. (If you know a curfew I’ve overlooked, please email me.)

The curfews, first set Saturday, May 30 (like two dozen other cities) after protests in response to the police killing of George Floyd fell to widespread looting and vandalism, were technically declarations of emergency “related [to] imminent danger of civil disturbance, disorder or riot in Philadelphia.” (Find Saturday’s executive order here.)

“The City experienced unprecedented levels of vandalism, violence, and looting over the past week. Criminal activity was significant at night,” wrote Kenney spokesperson Mike Dunn in an email to Technical.ly; indeed, there were at least 150 explosions. “Curfews were needed to keep people safe at home and protect property throughout the City, and to prevent and discourage further criminal activity.”

To contrast the widespread destruction of last weekend — from Center City to Kensington to West Philadelphia — most protests have proved peaceful. In describing the size, scale and longevity of these protests, one historian said in response to the tens of thousands out in Philadelphia Saturday: “The breadth of the Floyd protests is staggering.” Across the country, voters by a two-to-one margin are more troubled by the police who killed George Floyd than by violence at some protests. As the week wore on, criticism grew that the rare curfew tool was being misused.

https://twitter.com/tomsugrue/status/1269383576245743618?s=12

As of Thursday, nearly 500 of the city’s 755 civil-unrest-related arrests were due to code violations, primarily people who were still outside after the city’s curfews and protesters who failed to disperse when ordered to, according to reporting by WHYY — one of them was Pulitzer Prize-winning Inquirer reporter Kristen Graham. Some restauranteurs saw the curfews as another economic hit on top of the swirling pandemic.

The ACLU of Pennsylvania sent on Friday a letter to Kenney and other officials questioning whether the curfews were being used not to to quell “crime and disorder” but to constrain “overwhelmingly peaceful and orderly protest activity,” according to NBC Philadelphia. Citizens challenged the legality of curfews around the country, including suburban Los Angeles and in Palo Alto.

Dunn said city officials consulted daily with the Office of the City Solicitor to review their legal authority to proceed, balancing daily criminal activity data and real-time threats to public safety: “While looting has decreased since last Saturday and Sunday, recent levels remained significantly higher than what the City typically experiences,” Dunn said.

The curfews come at an already extraordinary time. The Floyd protests have brought forth a new national reckoning with the country’s lack of racial equity. Inequality has played out damningly during the pandemic, which rages on and was already the subject of states of emergency nationwide.

More than 40 states and territories have used states of emergency to control the flow of citizens in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. But Pennsylvania’s stay-at-home order for the pandemic is something else entirely than these curfews for civil unrest.

When the curfew was first enacted May 30, this reporter felt an unease — ought government restrict the free-flow of people during such a pivotal and raw movement? It’s no question rare.

The City of Baltimore used citywide curfews in 2015 in response to riots that followed the killing of Freddie Gray. In Philadelphia in 2011, the Nutter administration deployed youth-only curfews in response to flash mobs — despite public outcry. (Find here the Philadelphia Police Department enforcement ordinance for those “flashmob” youth curfews.)

Citywide curfews appear to not have been enacted when the Republication National Convention was held here in 2000 or during violent standoffs between Philadelphia Police and MOVE or other moments of widespread tension. In messages, multiple historians or city watchers pointed back to the 1830s and 1840s for other periods when curfews were likely used.

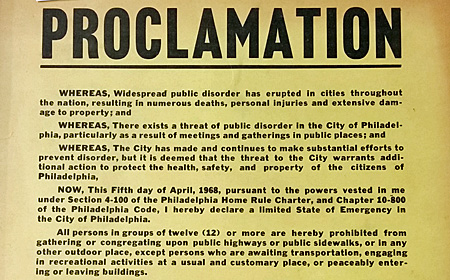

In April 1968, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., then Mayor James H. Tate and his Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo issued a heavy-handed state of emergency, making gatherings of 12 people or more illegal. But even that doesn’t appear to be a curfew, according to an original archive of that order, which is depicted below courtesy of a local history collector.

It’s one of the reasons why 1964 stands out as so memorable in Philadelphia, where the summer of 1968 was more muted than in other U.S. cities.

In addition to official city communications channels and through local media, the curfews were broadcast to participating citizens via text message (see above). These “wireless emergency alerts,” which the federal and state governments offer too, were similar to the text message system the city has maintained for its COVID-19 response.

Dunn says the Kenney administration hopes this will have been the one and only time they use the extraordinary power.