Warren V. Musser, who went by the name Pete, died early last week at 92. He was one of the global giants of venture capital. It is no exaggeration to say that in the pantheon of investing — in startup and early-stage companies — Pete was as big (although not as well known) as his peers such John Doerr, Bill Draper, Don Valentine and other luminaries from Silicon Valley.

Pete’s almost seven-decade record puts him in the conversation as one of the greatest venture capitalists and successful investors in the history of the planet. The case could be made that Pete’s track record was better than any one of those guys without the benefit of the Stanford or Cal Berkley startup machine. He didn’t have a big-time research university focused on turning out commercial companies.

Yet the names of his unicorn companies are household names: Comcast, Franklin Mint, QVC and Novell to name a few. One of his greatest investments is the Internet Capital Group, whose founder, Walter “Buck” Buckley, literally learned the venture investment world by carrying Pete’s briefcase. ICG, which went public right in the middle of the dot.com boom, had boasted three executives whose paper stock was worth $2.5 billion or greater.

Pete lived up to the reputation of the Greatest Generation as he served in the military, went to Lehigh University on the GI Bill, had four children, and with his college roommate, Vincent “Buck” Bell, bought a company called Safeguard Scientifics, which created a flawless bookkeeping program called the “one-write system.” I would know, because as an entrepreneur who had to do his own bookkeeping in the beginning, I was a total disaster until I used that system.

I had always sought out mentors, and when I first started working for Pete, I asked him if he would mentor me. We were at breakfast at one of his favorite locations when he told me that no one had ever asked him to mentor them before. I was as shocked at his response as he was apparently about my request. Although we didn’t meet formally to discuss my thoughts and concerns, Pete managed to mentor me through his actions and my observations.

Here are the 10 things I learned from Pete.

1. Back up the big thinkers.

When the first of five Technology Leader Venture Funds was being launched in early ’90s, the region’s venture capital community laughed at Eastern Technology Council’s (ETC) launching of a $50 million seed fund. At our monthly board meeting, I relayed the sentiments of the community and Pete bent over and quietly said maybe we should start with something like $25 million. Hubert Schoemaker, cofounder of the ETC and a giant in the biotech field, nodded and asked for the phone, then called the managing director at JPMorgan, Clayton Rose. He asked me to repeat what I heard and asked Clayton for his thoughts.

Clayton thought that the climate for raising such a large amount of money was going to be difficult, and on top of that, it is only Pete and his team who had venture experience. Hubert promptly told him he understood their concerns, but surprised everyone by raising the amount to $100 million. Pete said, “Hubert, I know you went to Notre Dame and that you got your Ph.D. from MIT before you were 21, but maybe math isn’t your strong suit, because it turns out: $100 million is more than $50 million.”

Everyone laughed and then Hubert reminded Pete that he was one of the greatest investors of the 20th century and that with the other CEOs around the table, they not only would make it happen but do it in 90 days. Pete tapped Hubert on the shoulder and said he liked Hubert’s audacious goals.

2. Support your people.

When I was being interviewed for the ETC job, I told Pete that one of my missions is to start the country’s first formally organized angel investors group, which turned out to be the Pennsylvania Private Investors Group, now the Private Investors Forum. Pete said he would be and was the first angel. His name was magical and attracted other top tier investors to join.

3. Share the value with your investors.

Under Pete, Safeguard pioneered the “rights offering” where shareholders would get shares of companies Safeguard invested in without tax consequences until they sold the shares. Pete looked at investors’ money as a sacred trust because he knew it was fueling college educations and retirements. Unlike many organizations where only the top executives’ benefit, Pete made sure everyone directly and indirectly got a slice of the pie.

4. Publicly admit when you are wrong.

We have all observed many leaders who will tell a room full of people when they think someone is wrong by embarrassing or humiliating them. One of Pete’s best qualities was his ability to take responsibility and tell the same group he was wrong. This experience happened to me on several occasions.

The first time this happened was when I invited the founder of Data General, Ron Skates, to be one of our “Titans of Technology” speakers. Pete questioned in front of the ETC board why I would choose an old-school technology company, whose best days, in Pete’s view, were behind it. Nevertheless, he didn’t override my decision and hence we hosted Mr. Skates.

The night before Mr. Skates spoke at our quarterly breakfast at the Franklin Institute, we hosted a dinner for him in the Safeguard board room. At the end of the dinner, as I was thanking everyone, Pete asked to say a few words. He told the room, which was comprised of our board and some other CEOs, how he was against inviting Mr. Skates, but after speaking to him about how he started the business and where it was going, Pete told the group how he was glad I stuck to my choice and that from now on he wouldn’t question my judgement on speakers.

That didn’t stop him from questioning other ideas, but when those ideas bore fruit, he was quick to tell the same audience how he was wrong. I never abandon that principle and remind the leaders I work with how much goodwill admitting publicly you’re wrong will buy and that it positively affects one’s overall corporate culture.

5. Loyalty is above all else.

I was sitting in Pete’s office talking about a new venture when his secretary said that a close friend of Pete’s was on the line. Pete said I could stay and just not say a word. He put the entrepreneur on speaker and the entrepreneur told Pete that he never thought his stock would fall so far and now he was upside down to his bankers for a significant amount of money. Pete said he would have it wired right away. He didn’t dodge the call, didn’t chastise the entrepreneur’s strategy nor negotiate the terms.

Pete turned to me and told me that when your friend’s house is on fire, you offer unconditional support and you don’t negotiate the cost of water, because one day your house will be on fire. Pete’s business house had a massive out of control fire and a great number of those he helped jumped in and rescued him.

6. Fortunes are meant to support society.

He was the most generous entrepreneur I have ever met. I was on the board of my hometown library and when they needed money for books, Pete wrote a check for $5,000.

I joined the board of an organization that focused on helping young African American men become leaders and entrepreneurs and asked I Pete to hear their story. Pete listened and left the room, which I assumed meant that the organization’s mission didn’t move him. I shrugged and apologized to the executive director, but two minutes later he handed them a check for $50,000.

7. Set high standards and goals.

One of the greatest learning experiences I had was the semi-annual Safeguard partners meetings that started on a Thursday and ended Friday afternoon. Each leader of a Safeguard company would brief the executive team and board of Safeguard along with outsiders like me and the legendary Philadelphia Eagles Dick Vermeil and Ron Jaworski.

At my very first partners meeting, each of the partner company leaders was sharing why they weren’t succeeding. By the second day, Pete cut it short and put everyone on notice that their performance had to improve, or we wouldn’t be seeing them in six months. The partner meetings were great because you learned about a lot of different industries and how leaders collaborated, but what I learned most was about setting expectations and holding people accountable.

8. Provide people with second chances.

Pete was a collector of talent. He started what he called the “orphans’ program” where discarded leaders could rehabilitate their reputations and careers by finding a venture for Safeguard to invest or running one of the Safeguard companies. Numerous companies and shareholders benefited from this approach because he knew these guys were hungry and had plenty of gas left in the tank.

9. Cultivate diversity.

The very first Safeguard board member I met at the semi-annual partners meetings was Delbert Johnson, an African American man who had worked his way up from the shop floor to owning the manufacturing company he worked for. He later became the first African American to chair a regional Federal Reserve Board. Later, Pete appointed Del’s brother Jerry, a former schoolteacher and COO of US West, as Safeguard’s president and COO. Pete also appointed a Jean Smith, as president, until she left for a different opportunity.

There was no pressure for Pete to add people of color and women to his board at a time when there was even less equitable representation than there is today, and in any case, Pete wasn’t the type of person you could force to do anything. He would do something because it was the right thing to do and it made sense.

10. Live simply.

Pete wasn’t a mansion-Rolex kind of a guy. He did drive old Jaguars because he looked cool in them, but he mostly drove American cars. He didn’t wear expensive clothes. He was more like a midwest Warren Buffet than a sleek Wall Street guy. The only reason you would need a written agreement with Pete is to remember what everyone agreed to. He was a man of high integrity and always shot straight.

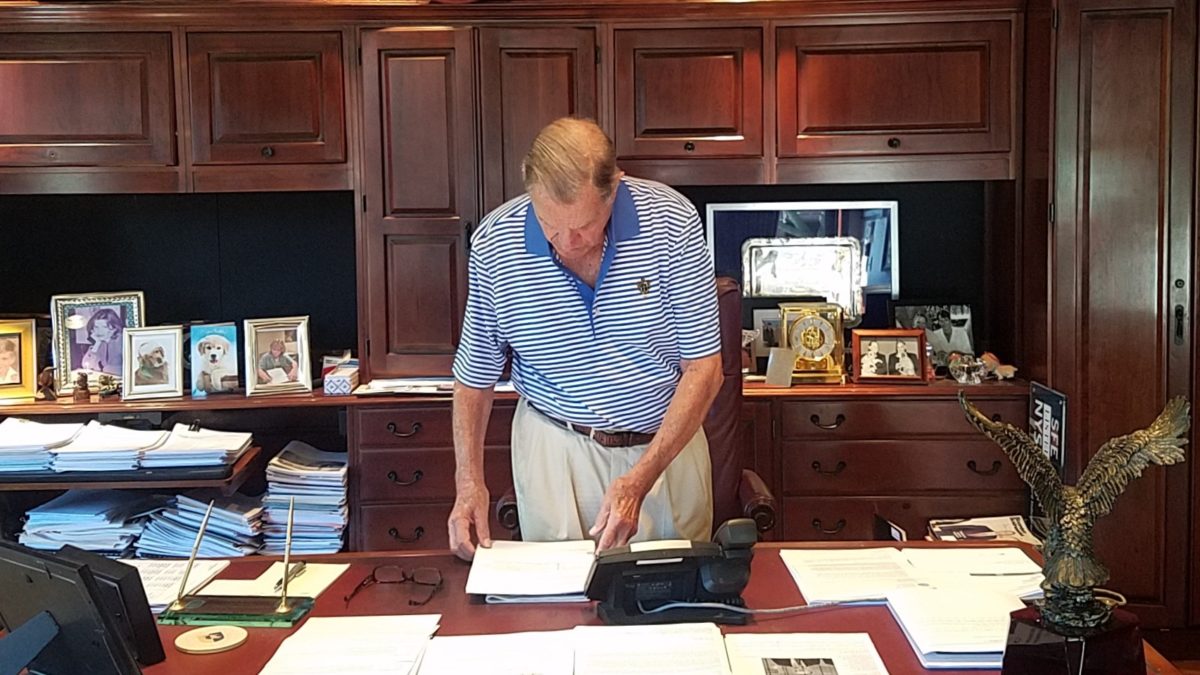

No one who worked with as many companies as Pete had a clean desk. You wondered how this godfather of the venture world could oversee so many enterprises yet never had more than a few pieces of paper. The answer was picking and supporting smart people and letting them worry about the details.