Right in the geographic center of Baltimore, a group of Reservoir Hill neighbors have grown fond of the area’s historic homes and its proximity to Druid Hill Park. But the community of people from all walks of life has proven to be the real draw. After spending several years convening residents in the wider Central West Baltimore area, they learned that their own pocket isn’t unique.

“It became very clear that the creative class and innovation economy was really our core competency here in this part of the city and what could really generate the biggest outcome for our future,” said Dale Terrill, who is vice president of the board of the Mount Royal Community Development Corporation (MRCDC), a group formed by the neighbors to put a strategy behind that insight.

Now MRCDC is sponsoring a framework for economic development that puts startups and small businesses at the center of revitalization.

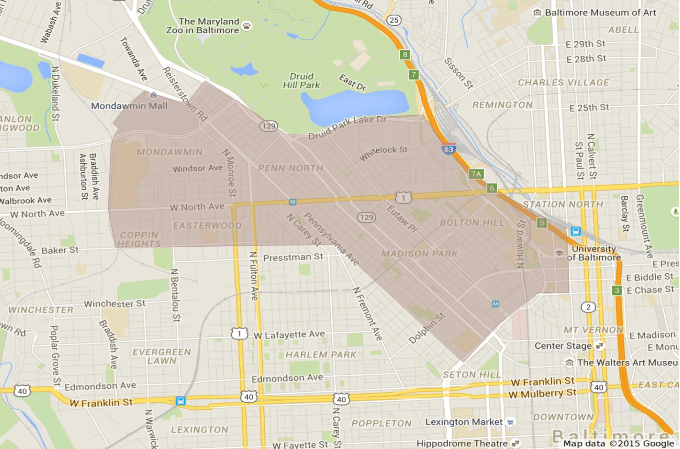

Innovation Village is set to encompass 6.8 square miles across the central section of West Baltimore, spanning from Mondawmin to Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. A Monday morning announcement with city leaders at Penn and North marks the public launch of the effort. Details on specific projects within the area are expected in the coming weeks and months, but the designation of the area is a thing in itself.

“It’s a framework that allows for input from community organizations, from anchor institutions, entrepreneurs, from every sector of the community,” said Richard May, an MRCDC cofounder.

Drawing on the innovation district model that has been applied in areas like downtown and midtown Detroit, Boston’s Seaport and Philadelphia’s University City, the framework looks to bring startups and entrepreneurs close to anchor institutions and large firms. Instead of the sprawl that spawned Silicon Valley, innovation districts focus on tightly packed areas where the high concentration of companies and entrepreneurs with access to big institutions, transportation, parks and other urban assets gives way to an elevated quality of life throughout the area.

“Innovation is heavily dependent on proximity,” May said. “How close are you to others that can make that idea come to life?”

It’s a model that has resulted in explosive growth in those other cities, with lots of new companies created and more of those big firms moving in. (Witness: Just last week, GE announced that it would move its headquarters from suburban Connecticut to Boston’s Seaport.)

The Innovation Village team wants to bring that same kind of growth to Central West Baltimore. Along with new jobs and businesses, the effort also has a built-in goal of improving life for residents in an area of the city where Baltimore’s decades-old inequalities come into sharpest relief, and have been most visible in national news coverage. Echoing similar themes we’ve heard from AOL cofounder Steve Case and White House officials, there is a core belief that extending startup and entrepreneurship resources to low-income communities can be a new solution to decades-old inequalities.

MRCDC Executive Director Andre Robinson said the millennial generation driving that entrepreneurship realizes that the future doesn’t look bright if inequality continues. Equally important on the neighborhood level is a willingness to cross old boundaries.

“They’re much more comfortable crossing over and blurring all of those lines,” he said. “The disruption mentality that comes from the innovation and tech sector … they can bring the same sensibility to, ‘Why does our neighborhood look that way?'”

The team members we spoke with acknowledged that bringing the vision to fruition will involve hard work that spans technology, business development, real estate, community organizing and more.

“If you just focus on one, you’re not going to find the results that you want,” said Terrill.

There was also acknowledgement that past plans in West Baltimore, like James Rouse’s $130 million investment in Sandtown-Winchester, have little to show. But the core of residents spearheading the project believe this effort is different because it seeks to take advantage of assets West Baltimore already has, and comes directly from the community.

Before they were members of MRCDC, they were neighbors.

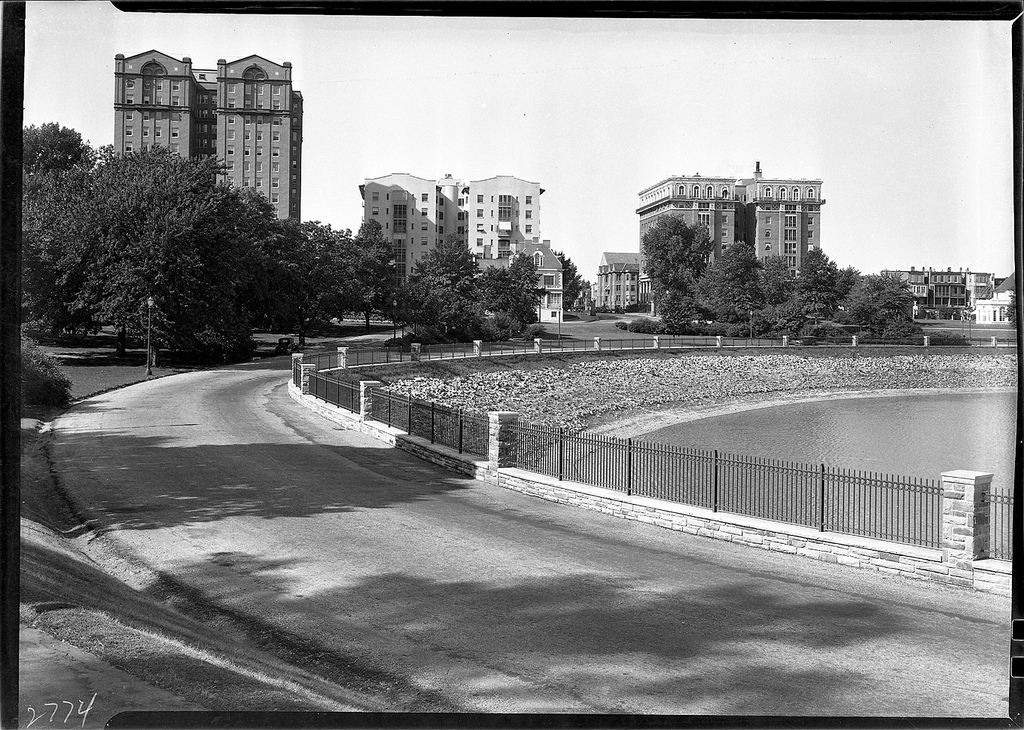

May, who moved to the neighborhood in 2010, was working on a TV film project called Good Fellas of Baltimore with Andre Robinson. May soon met Kevin Apperson at the annual New Year’s Day party. Terrill moved there in 2011, and loved the neighborhood so much he wrote a book about its history the next year. Another neighbor is Jacob Green, a Johns Hopkins grad who moved to the area in 2005 and built a company in the Emerging Technology Centers. Between their varied pursuits, they chatted in kitchens and got together at events.

As they worked on the projects that brought them into contact with more people and got involved with community groups, the neighbors saw that their group wasn’t just a pocket of West Baltimore. As they came to see it, the area’s well-known poverty was a question of resources, not talent.

“The MRCDC grew out of looking at the area and realizing there were a lot of great organizations doing great work, but there was really a need for a community development corporation that could weave together all the assets,” May said.

Formally cofounded by May and Apperson in 2013, the organization became the vehicle to lay out economic development plans. “It was a true startup,” said Terrill, who acknowledged that he never thought of himself as an entrepreneur. Team members invested their own money. The core members now have board officer titles, but they each do a little bit of everything.

As the focus has shifted toward a larger vision, more members of the community joined the process.

There was a lot of research involved, but another big focus was on building community and allowing folks to make connections, and weigh in on what they thought the plans should be for the future. That’s where events came in. Neighborhood meetings in Reservoir Hill gave way to collaborative meetings with other groups where hundreds of residents showed up. At happy hours and resident gatherings, they would drill down on specific topics, like the future of North Avenue.

“There’s been since Day 1 a very serious effort and sincere effort to make sure this includes everyone, no matter what walk of life you are,” Terrill said.

Through the meetings, more residents came forward and offered their talents. That’s how MRCDC envisions further growth. The mayor’s office is also now involved. Talent attraction is part of the goal. But another big focus of the long process for MRCDC was to keep the focus on retaining people who are already in the area.

“The people that are going to staff these companies can come from the community at large, as well as the universities. That’s the kind of talent that we’re looking for and we’re looking to hold onto it,” said Green.

Currently the president of the MRCDC board, Green moved to Baltimore from Detroit attend Hopkins, then worked on a startup called D-Fusion that grew out of his graduate research. After starting another distributed systems and networking tech company called SpreadConcepts, he is currently director of engineering at LTN Global.

“Startups are looking for good talent, connections and capital. They need access to transit and a friendly environment. We have those ingredients,” Green said.

The team believes many of those assets are already there.

The ingredients include three forms of transit nearby, from four subway stops to light rail to Penn Station close to the eastern edge. There is also direct access to I-83. Universities have been key partners in Innovation Districts in Philly and Atlanta, among others. In Innovation Village, MICA — whose community involvement in Station North is well-documented — and Coppin State are already partners, and MRCDC members point out that the University of Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University and Morgan State surround the neighborhood.

In a statement, MICA President Sammy Hoi said the Innovation Village is “the kind of multi-sector partnership initiative that we need to nurture a next wave of innovation-based enterprises to help create jobs, increase city revenues, provide equitable access to opportunities, and transform neighborhoods.”

Druid Hill Park is also nearby, along with retail at Mondawmin Mall, which is in the footprint. Another piece of the puzzle in other cities has been available land to develop.

By aligning these elements, the goal is to develop a community where entrepreneurs can live and work, just like what’s happening in downtown and Port Covington. The general idea goes that the entrepreneurs can bring growth to new areas as they seek options like retail, recreation and, of course, places to hang out. Along with looking down the road at how their company can change a marketplace in five years, entrepreneurs are also seen as more likely to look at a neighborhood in the same fashion.

One early aim is getting entrepreneurs from other parts of the city involved. To that end, Startup Soiree is set to host its January edition at Arch Social Club, located at Penn and North, on Jan. 27. Yet Analytics cofounders Shelly Blake-Plock and Margaret Roth will be talking about raising a seed round.

To Soiree cofounder Patrick Rife, bringing together a diverse set of entrepreneurs involves people from different backgrounds as well as what category the company operates in.

“I’m interested in opportunities and resources that are being produced for the majority of the city,” Rife said.

One early example of a gathering point already in the neighborhood is happening a few blocks from Druid Hill Park on Madison Avenue. A new neighborhood spot called Dovecote Cafe is becoming a gathering point. It’s one spot where B. Cole is working to connect a network of innovators of color from around the country through the Brioxy Innovation Network. In less than half of a year in Baltimore, Cole said she has already connected with hundreds of entrepreneurs who are ready to get their business or idea off the ground.

“We have an opportunity to put a generation of young black people on the path to success,” she said.