Guiding where $100 billion gets invested each year is an enviable task. Yet with great power comes great responsibility.

Most of the half-trillion dollars of donations in the United States last year were made by individuals reflecting their personal interest. The 20% that was distributed by foundations and other professional donors attracts special scrutiny. What’s the highest and best use of philanthropy?

“The need, the demand, will always outstrip supply,” said Jamie Sears, the managing director and co-head of social impact and philanthropy for UBS, which has become one of the world’s largest wealth managers.

Sears, in part, sent me in pursuit of the answer to this question. I met her years back through social impact conferences, and we’ve done projects together — notably, a podcast series called Off the Sidelines focused on bringing underrepresented high net-worth individuals into angel investing. As entrepreneurship surged during the pandemic — led by women and people of color — she took a self-reflective posture: Did a decade of charitable investments into programs and resources for underrepresented business founders actually contribute to that boom?

The result of that question was a landmark analysis by Technical.ly called The Inclusion Edge that UBS helped fund. The short answer is: Yes, probably — years of trials and culture change helped make it easier for Black women in particular to opt-out of traditional work and become self-employed. But stewards of thoughtful capital like Sears are resistant to any celebration. There’s too much work to do, which brought us in conversation to the question at hand. After years of chaotic pandemic devastation and social upheaval, how ought funders reflect on the balance of their priorities?

“The expectations from communities and organizations that we support have shifted,” said Nyra Jordan, the social impact investment director of the American Family Institute. She’s made investments around the country on a range of issues from economic opportunity to the arts.

The Four Traditions of Philanthropy

To understand how expectations have changed, it helps to go back to how we got here.

Philanthropy is an old concept. When wealth concentrates, there’s a longstanding moral imperative to distribute some of it. Historically, this had religious overtones, such as the concept of tithing across many traditions. In modern times, the American tax code has encouraged it. The federal government made donations to charities tax deductible in 1917 and formalized today’s concept of private foundations in 1969. Each philanthropist brings their own priorities, but tax-advantaged status comes with a mandate: Redirect these funds for greater societal good.

Over time, according to one framework popular among community foundations, American philanthropic priorities have followed in three traditions: relief, improvement and social reform.

- Relief: The oldest sense is that of charity urgently responding to crisis now — think, the soup kitchen feeding the hungry, or distributing water and medical supplies after a natural disaster.

- Improvement: After the Industrial Revolution, more prioritized root-cause obstacles of individual development — think merit scholarships, early workforce programs and Carnegie’s libraries.

- Social Reform: The last half century turned on the systems underpinning social inequities — think research and policy change, program development and a focus on data-informed and repeatable systems.

Now “there’s a trend in the past 20 years of going from this top-down approach of ‘we know what you need over there’ to designing with community, and hopefully, we’re evolving into a place where we’re designing by community,” said Caroline Barlerin, the CEO of Platypus Advisors. She founded the philanthropic consulting firm after stints leading corporate philanthropy at Twitter and Eventbrite.

This fourth tradition is civic engagement, in which funders invest as close to communities they serve as they can.

“Build ‘with’ design ‘by’ — not ‘for,’” Barlerin says — putting her prepositions to work. The pandemic era didn’t create this trend, but it could be remembered as a defining part of it, as Barlerin predicted back in 2020. Invest in on-the-ground efforts with proximity.

Effective altruism and ‘longtermism’

Investing locally may sound like an unquestioned good, but there are criticisms — including among certain modern moral philosophers and ethicists challenging philanthropy today.

Most cases of what philosophers call “reciprocity,” in which one person feels compelled to advantage someone who is geographically nearer over someone else who is farther, is an outdated line of thinking, said Brian Berkey. He’s a business ethics professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and was part of a Technical.ly special report last year on international hiring.

Better yet for philanthropists to focus on wherever their dollars can improve the most lives. This is the heart of what is called “effective altruism,” an emerging research field focused on identifying the world’s most pressing problems and most efficient solutions. A popular example is that mosquito nets are one of the world’s most cost-effective tools for improving quality of life by reducing malaria contraction. It doesn’t cost much to relieve that pain in low-wealth parts of the world, which can help people live longer, happier lives — often boosting incomes and the likelihood of having children themselves, creating ripples across generations.

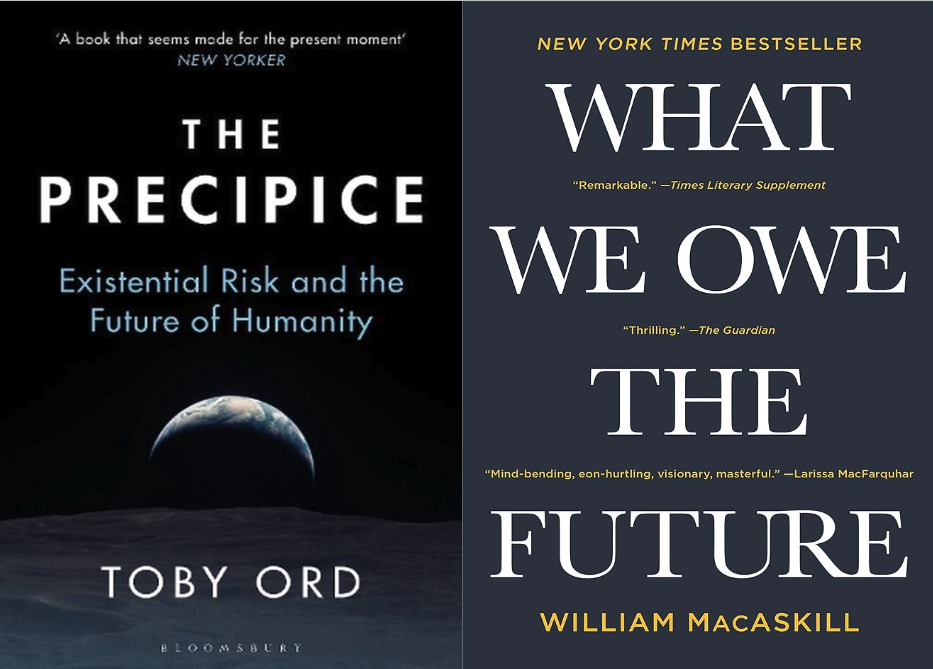

One theme of effective altruism that considers these multi-generational effects is the concept of “longtermism.” The term has been popularized in recent years by books like Toby Orb’s 2020 book “The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity” and William MacAskill’s 2022 book “What We Owe the Future.”

Longtermism argues that there is no moral difference between caring about a stranger 150 miles away and a stranger who is 150 years away — or thousands of years for that matter. This is not so different from the famous Seventh Generation Principle credited to the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois, people, in which decisions today should be in alignment with our ancestors from several generations before us and our descendants who will live seven generations from today, which could be 150 years hence.

Effective altruism and longtermism are among the most en vogue challenges to contemporary standards on morally responsible philanthropy. Where do we go next?

Follow your expertise and “be in community”

When compared with malaria nets in Malawi, supporting, say, a pro-entrepreneurship program in Milwaukee (or storytelling about it) will seem especially expensive and indirect. Why not drop everything and redirect all funding toward the most cost-effective interventions?

Effective altruism asks important questions, but Barlerin doubts whether it’s desirable (let alone even possible) to coordinate all the world’s philanthropic dollars around one problem at a time. Social issues are deeply entwined — malaria exposure with housing and education, like entrepreneurial access is with awareness and network effects.

“Through diversity of philanthropic approaches — from short-, middle- and long-term views — we’re going to get more innovation and we’re going to unlock more intersectional solutions that are required for the complexity of the problems that we’re tackling today,” Barlerin said.

As individuals and foundations, donors should scrutinize their investments and make them across “the capital stack.” Relief forms of philanthropy are increasingly left to government and religious groups, but when the hurricane hits, there is a very real and urgent need for others to contribute.

When the storm subsides, attack root causes. There, professional philanthropy can go beyond just dollars, and incorporate expertise. Regulations govern private foundations and corporate philanthropy, especially from financial institutions, which contributes to their geographical and topical focus. Helpfully, this can align with a funder’s expertise and network.

“Instead of just mailing a check to the best-known nonprofit, find those closest to a problem and ask them what they need,” Barlerin said. Invest where you have other resources to give, too, she advised.

As a wealth management firm, UBS, for example, has identified that growing business ownership among women and people of color addresses wealth inequality — that’s a philanthropic goal that benefits from the expertise the firm has. That’s why Sears has developed a portfolio of programs, organizations and investments that drive at the goal of increasing the skills, network and stories of underrepresented entrepreneurs.

“The need for more sustainable investment is so important,” Sears said. “And it’s something that we can all do from a process standpoint.”

Or as Jordan from American Family Insurance put it: Trust, try, learn and listen.

Sears added: “The answers come in partnership and in community.”