OK, but what is 3D printing good for besides prototyping?

It’s a question that’s increasingly important for Brooklyn’s tech scene, which continues to rally around additive manufacturing. It’s also a question I asked this summer to Elias Bakken. Bakken is a Williamsburg-based technologist who invented a “cape” that allows desktop 3D printers to be retrofitted to interact with a network rather than be tethered to a computer.

“Probably more localized manufacturing of goods,” he replied. “It depends on what perspective you have. My factory is in China. It’s a lot of work, you have no idea. Half my day I spend writing emails to China. Logistics is hell, man.”

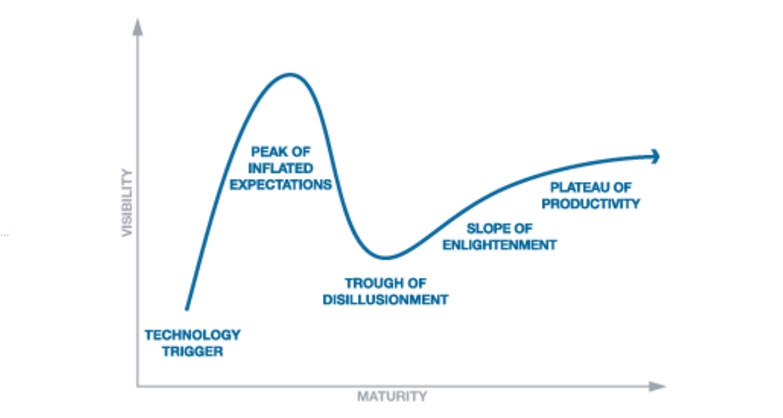

Bakken said he thought 3D printing was in the trough of disillusionment on the Gartner Curve.

What’s that, you ask?

The Gartner Curve, or the Gartner Hype Cycle, is a concept for emerging technologies which predicts they’ll go through five stages: it starts with technology trigger, soars up to peak of inflated expectations, crashes down to the trough of disillusionment, then glides back up to the slope of enlightenment, and continues on to the plateau of productivity.

This psychology is naturally different for different products in their own markets, and the timeline for these events will be different accordingly, but Gartner believes each technology will go through the cycle at one time or another.

There is plenty of reason to believe that Bakken (and Gartner) may be right, or at least mostly right. There has been plenty of bad news in 3D printing this year. MakerBot seemed to be floundering earlier in the year, hiring its fourth CEO in two years and firing 20 percent of its staff.

“Today, we at MakerBot are re-organizing our business in order to focus on what matters most to our customers,” the company said in April. “As part of this, we have implemented expense reductions, downsized our staff and closed our three MakerBot retail locations.”

In June, Time magazine published an article titled, “Was 3D Printing Just a Passing Fad?” In the article, the author noted that heady valuations of public 3D tech companies were crashing:

Since early 2014, most of the stocks in the 3D printing industry have collapsed. Stratasys, 3D Systems, ExOne and VoxelJet have lost between 71% and 80% of their market value in the past 17 months. The reasons why are nothing new to investors who have speculated too early in promising technologies: Profits can be hard to come by, and revenue can fall short of expectations.

In an interview with Technical.ly Brooklyn, 3D printing company Matter.io’s CEO Dylan Reid expressed his dissatisfaction with the limitations on 3D printing.

“People would talk about all the innovation happening in 3D printing then pull a 3D-printed Yoda head out of their pocket,” Reid said. “But that technology is useless without an application.”

So if we are in the trough of disillusionment, then the next phase would be the gradual increase of reformed expectations into the slope of enlightenment. This period would be marked by excitement over modest but meaningful advancements. And this is something we’re seeing.

Last month, Technical.ly alumnus Andrew Zaleski wrote in Fortune about doctors using a 3D-printed prototype of a 5-year-old girl’s heart.

Earlier in the year, MakerBot’s parent company, Stratasys, announced that it would enter into a partnership with Airbus to make more than 1,000 3D-printed end-use parts for Airbus planes.

Matter.io, for its part, is leaving Brooklyn for Manhattan because it’s doing well enough to expand, hire employees and pay a higher rent, Reid said.

And on top of all that, former MakerBot engineers split from the company and set up a 3D printing studio called Voodoo Manufacturing in East Williamsburg this fall. As you might expect, its founder, Max Freifeld, is tremendously optimistic about the industry, but also realistic about expectations.

“3D printing as an industry has had a lot of hype,” he said in an interview on the opening of his company’s new office. “I think the next 10 years is going to be 3D printing realizing a lot of that hype.”

He said that 3D printing for small-batch items wins not just on novelty. but also on price and service, as compared with injection molding.

“We want to make manufacturing just stupid simple. Because we’re using desktop 3D printers, this is becoming viable,” he said.

And Bakken, too, is unflagging about the future of 3D printing.

“Further in the future, you’ll be able to use every material on the periodic table, and then you’ll be able to make anything,” Bakken said at the end of our interview. “That would be the holy grail.”

OK, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Plenty of curve still lies ahead.