Deb Diamond told me it’d be a damn shame if Philadelphia added 68,000 college-educated young people and remained what it has been: a poor city tortured by shadows.

Between 2000 and 2017, Philadelphia city’s population of bachelor’s degree-holding 25-to-34-year-olds surged by 115%, eclipsed only by Washington D.C. — and beating places like Seattle, Boston, Los Angeles, New York and San Francisco.

Way back in 2010, Campus Philly, the regional research and retention nonprofit that Diamond leads, noted that brain drain was no longer a problem for Philadelphia. For college students who took classes between 2010 and 2014, more than half stayed in Philadelphia, outperforming Boston for the last decade.

Diamond doesn’t even seem to name the old, dead “brain drain” curse anymore. In truth, I suspect she finds the phrase rather tiresome — she’s been talking about it for years, after all.

“We call it the Philadelphia Renaissance,” said Diamond. She was sharing the highlights from Campus Philly’s annual report at an event on Thursday evening. But it speaks to Diamond’s outlook of this place. That outlook is a bright and sunny one. But now that we keep around plenty of educated, young people, we need to do something important with them.

See the report

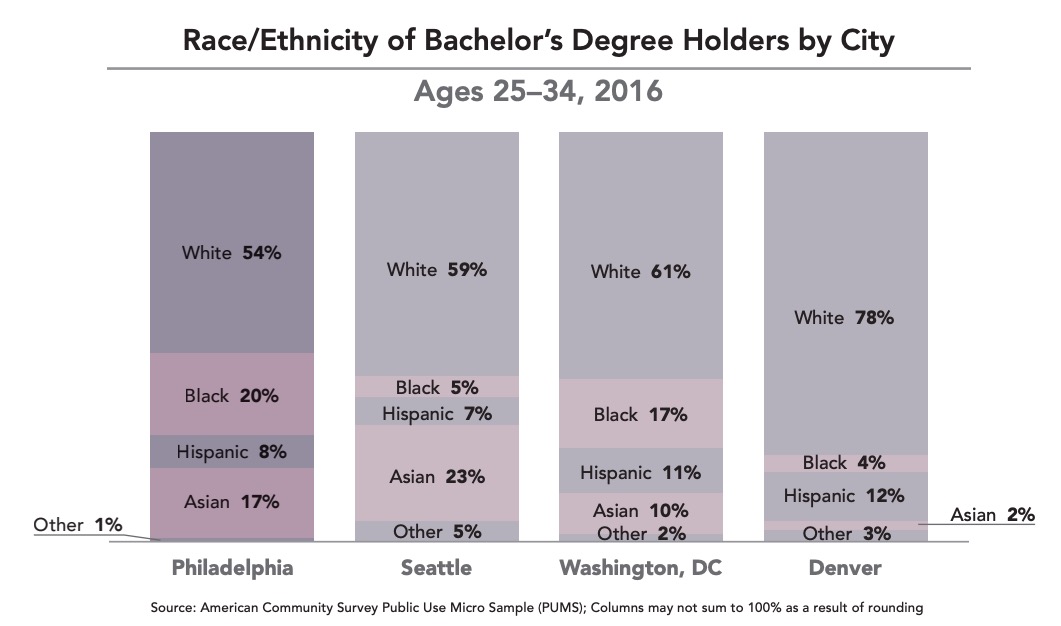

The graduates here are also more diverse than those from other cities, as 46% of them are people of color, compared to 41% in Seattle, 39% in D.C. and, well, 22% in Denver.

But for the lives of many Philadelphians, things haven’t gotten better. Philadelphia is still the country’s poorest big city. Income inequality is now worse than any other, save for Miami and Atlanta, thanks in part to scattered pockets of wealth creation.

“How can everybody benefit?” asked Will Toms. He’s the energized cofounder of REC Philly, an organization for creatives that brings together education, community and services for paying members who might be filmmakers, DJs, podcasters and the like.

Toms was part of an on-stage discussion that followed Diamond’s remarks and was moderated by this reporter; the conversation was meant to bring to life that data and research Diamond’s nonprofit gathers annually. Raised in Germantown and Bucks County, Toms aims to represent hundreds of these Philadelphia millennials who might otherwise sink into today’s service-sector poverty.

“Artists want to know how to be truly independent,” he said.

Toms was joined by Dominic Salerno, a tenured professor at the Community College of Philadelphia. Salerno is part of the Biomedical Technician Training Program that CCP is running with The Wistar Institute, to give a different-profile student a shot at a highly technical, high-paying career.

Civil service is still a powerful, effective and “cool” upwardly mobile employment opportunity, especially for women and people of color, noted Sara Hall, a product manager with the City of Philadelphia working on phila.gov.

Independent creatives, lab technicians and eager civil servants are, indeed, collectively powerful tools for helping to make a better educated Philadelphia more equitable. But economic development executives and policymakers tend to look for new, growing employers to have outsized impact.

It’s why the highly scalable tech sector is so much discussed. And that’s why goPuff, the on-demand delivery service, is thought to be an important part of this story too. With thousands of just-in-time drivers and distribution centers around the country, it’s perhaps Philadelphia’s only truly consumer-facing tech startup at a national scale.

“We’re committed to Philadelphia,” said Rafael Ilishayev, one of the Drexel University students turned goPuff cofounder.

Last fall, the team announced they had bought and were making a more than 30,000-square-foot headquarters out of the former Finnegan’s Wake bar at Third and Spring Garden streets. Ilishayev said the company will have 250 employees there when they expand there this summer; it currently has staff working out of the reception area of its over-stuffed headquarters in Callowhill.

Backed by a $400,000 state grant, that announcement included distribution centers and jobs elsewhere in Pennsylvania. But Ilishayev said the company had to look away from other states trying to lure them away with cash. For example, New Jersey successfully sold goPuff on expanding with a 300,000-square-foot facility with the help of a $39.1 million tax incentive package. That much we knew. But Ilishayev added that New Jersey officials had also offered a $50 million package to relocate their entire headquarters to the Garden State.

Between city and state officials here, Ilishayev said goPuff was offered a package closer to $2 million — “that’s not even 5%” of the New Jersey offer. He said he wasn’t even expecting to be offered the same, just surprised by the disparity.

Lots of research shows offering tax breaks to companies is, at best, complicated policy. But Ilishayev isn’t a policymaker. He’s a cofounder of a company with decisions to make — “and $50 million is a lot of money,” he said.

Deep inside the Campus Philly report is one foreboding chart. It’s a simplified look at which degrees are most likely to be in that 54% of graduates who stayed, and who might be most likely to leave.

Those who stay tend to be quite vocational: nursing, accounting, criminal justice and, heaven help us, journalism. Outside of mechanical and electrical engineering, there are few degrees that might lead you to believe they’d predict a surge in new economic activity. In contrast, graduates more likely to leave include those who studied things like entrepreneurship, project management, business, IT and computer science — degrees that, at least for now, are more associated with higher-growth possibilities.

“Maybe we’re still losing some of our best,” said Ilishayev. (We also can turn our attention to mid-career losses.)

Philadelphia has already changed. It’s growing. It’s smarter. It’s important to name that as a true success. But we’re still quite poor, and those who are most likely to change that the quickest are those who are the most likely to leave.

In Diamond’s remarks, she noted that though one in 10 of Philadelphia’s graduates still end up in New York, that number is likely smaller than many would predict, and there simply aren’t any other cities that draw that many more from Philadelphia than anywhere else. The data show that Philadelphia doesn’t have some outsized adversary that is keeping us poor and violent and stigmatized.

“Our competition isn’t one or two superstar cities,” Diamond said. “It’s ourselves.”