It’s early evening on a rainy spring Wednesday, and situated around a table in a meeting room downtown, the voices of civic tech in Pittsburgh have gathered to discuss the current state and possible futures of their work.

There are software developers working closely with companies to incorporate new tech into their systems. There are city planners who envision a Pittsburgh built on a foundation of free and open data. There are curious citizens coding for a better community, county employees who carry with them the weight of the big picture, and funders with an eye for innovation.

And, of course, there are staff from the public library.

Ten years ago, this might have warranted confused looks and cocked eyebrows. Now, however, the library taking a seat at this table seems obvious; more and more, libraries are a powerful voice in these conversations. Literacy, as we continually realize, reaches far beyond the pages of a book.

Where my work at the intersection of libraries and civic tech began is hard to pinpoint, because my suspicion is that I interacted with these systems far before I had a name for them. Whether in pursuit of research or curiosity, government and municipal data was not totally unfamiliar to me; a project here, a project there.

However, it was not until I began my graduate work in information science at the University of Pittsburgh that I started to understand the library’s role in the realm of civic tech. During this time, I was lucky enough to be a research assistant on the Youth Data Literacy Project with Leanne Bowler and Amelia Acker. Through a collaboration with The Labs @ CLP [Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh], we investigated approaches to data literacy under the umbrella of youth programming at the public library.

With a group of teens and librarians, we explored data from all directions. We disassembled old cell phones, mapped our library’s data access points and took a deep dive into the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center’s dog license data. Throughout this process, we asked these essential questions: What do teens know about their data? What do librarians know about teens and their data? What can public library programming do to address data issues and inquiries?

The pursuit of these questions sparked in me a profound interest in examining and expanding upon data literacy in the library. So, naturally, when the opportunity appeared to serve a civic information services internship at the Carnegie Library, I pounced.

Our team, led by Open Data and Knowledge Manager Eleanor Tutt, also addressed data literacy within the library. This time, though, the lens had shifted. What we hoped to find — and what we knew the library was uniquely positioned to provide — were enticing entry points where our community could engage in conversations about civic data.

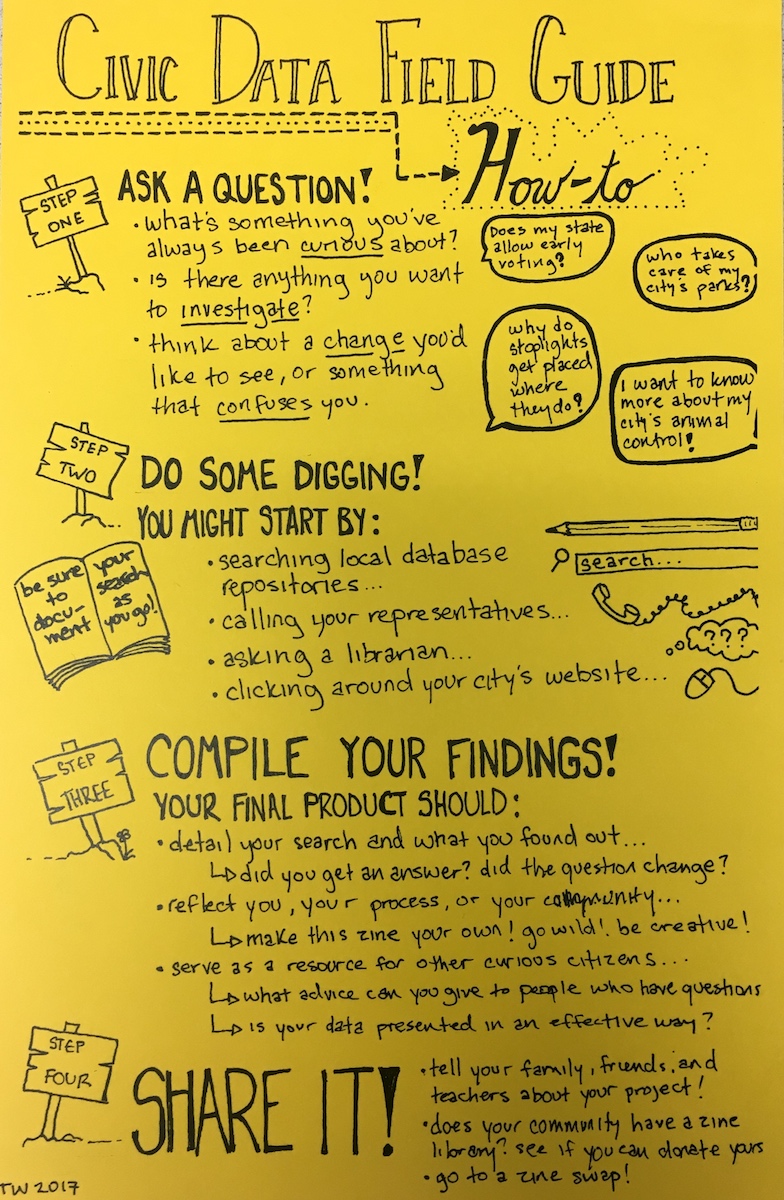

One of the most exciting parts of this position was the chance to continue my work with young people in Pittsburgh. In fact, I often use our Civic Data Zine Camp, which took place in the summer of 2017, as a starting point when answering questions about what exactly libraries have to do with civic tech.

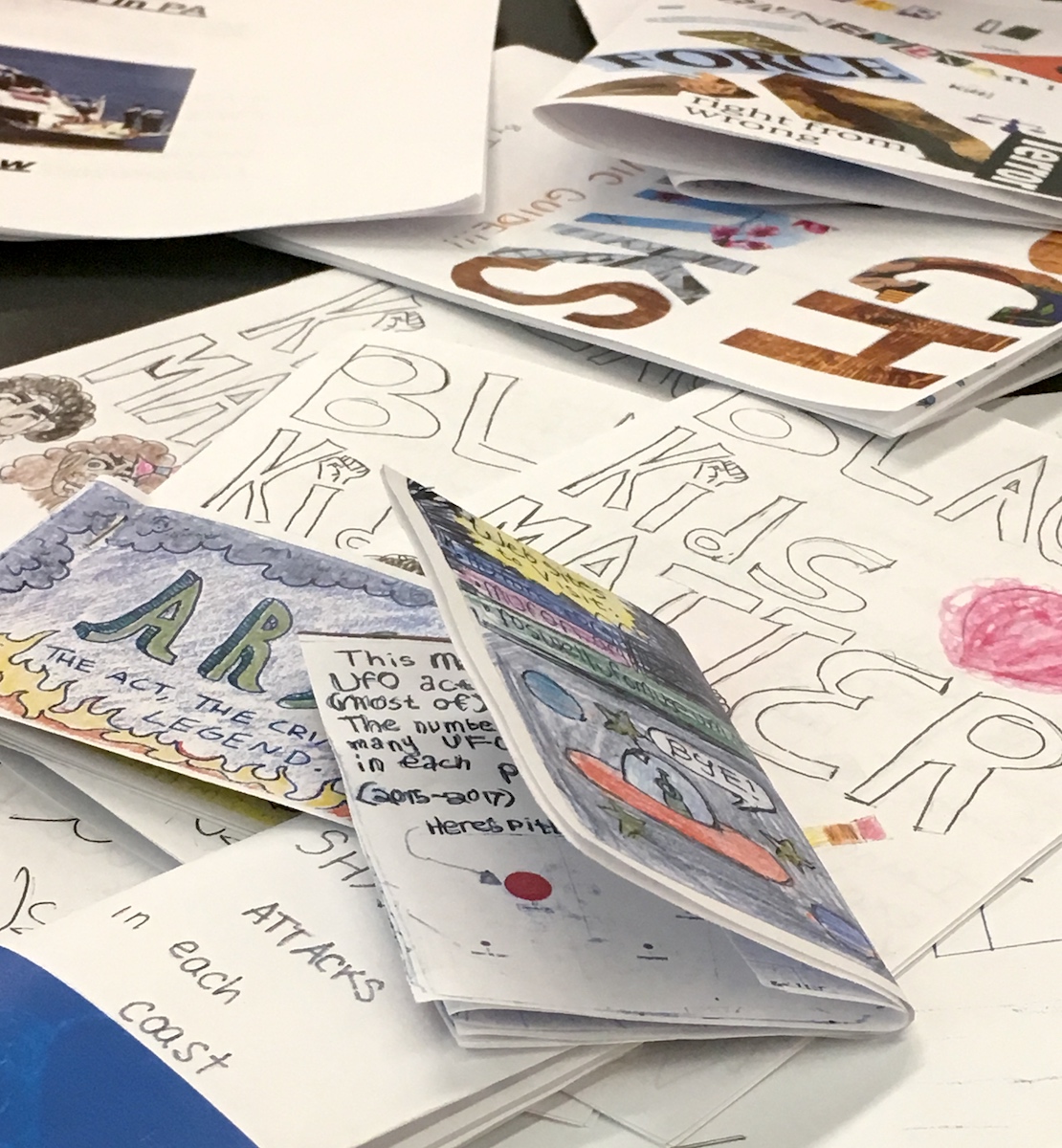

During this week-long workshop, teens examined an issue by employing open data and civic information resources. They then compiled their approach and findings into hand-crafted zines, which were shared with the group and now reside in the zine collection at the library.

This process, for me, is at the crux of what makes engaging with civic data so thrilling — the opportunity to use open data and civic tech as tools for civic change. Because when I talk about open data, I talk about opportunity and agency — the opportunity to investigate and the agency to disrupt. And this becomes especially vital when we consider who the public library serves.

Naturally, there are scholars researching and professionals analyzing. But there are also attentive parents wanting to know more about school trends, active commuters seeking out transit statistics, concerned citizens looking for crime data and curious children hunting for dog license registrations. By including folks who we might refer to as “non-technologists” in this dialogue, we help to encourage a more holistic and approachable conversation.

As a space built and sustained by collaborative community efforts, the library has the chance to serve as conduit between users and technologies. With this approach, we can begin the civic tech processes with inquiry, then employ innovation.

This is why the library has found its place at the table in conversations like the one on that rainy Wednesday — our work is inextricably tied to both parts of the whole, as we are eternally civic-minded and increasingly technology-driven.

Get Pittsburgh civic tech stories in your inbox weekly