Still, the popularity is leaving many wondering how, exactly, an NFT works, so Technical.ly spoke with a couple of Baltimore pros who have experience with NFTs to learn more about the technology, and why it’s having economic impact now.

In essence, a nonfungible token is digital verification that an item is authentic and unique. This is powered by the Ethereum blockchain, which is the same kind of technology underlying a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin or Dogecoin.

Essentially, NFTs are digital baseball cards and the Ethereum blockchain is the manufacturing plant to print the cards.

Software engineer Sunny Sanwar, who now runs the Baltimore startup Dynamhex and is a professor at the University of Baltimore, used NFTs with his team in 2018 to track solar energy production from individual homes. Again, NFTs are really more of a certificate of authentication using a digital currency. In Sanwar’s example, the blockchain code verified that a certain amount of solar energy was produced on a specific day, and went to a specific place. Users of Sanwar’s blockchain code weren’t buying solar energy, they were buying the verification that they had produced a certain amount of solar energy.

“If you get your bill from BGE, it gives you the total kilowatt hours. It doesn’t tell you exactly what electrons came from where,” said Sanwar. The blockchain code Sanwar created allowed users to track when, where and how it was produced, then track to who consumed it.

What’s the value in proof of authenticity?

Theoretical user Brian can’t take his crypto token made as verification of his solar energy and buy something at a store, like one could with Bitcoin. But if someone wanted to buy ownership of that solar from him or an energy company wanted to buy the energy produced from his home because he could verify the production of solar energy, that’s a different story.

Once the NFT is made, it’s up to Brian to find a market for it. Making an NFT doesn’t automatically equate to value.

“It has no meaning. If someone wants to buy it and pay four bucks for it, that’s up to them and I’ll sell it, but it doesn’t have a relevance in the real world,” said Sanwar.

Buy blockchain verification/equity/make NFT → ???→ profit.

2021 is where the missing link to profit from an NFT became more widely known.

Sanwar compared the whole thing on a theoretical level to the sale price of the house from the movie Home Alone. It’s built with the same wood as any other house, but it was sold for $1.5 million, while the house of Old Man Marley in the film across the street sold for $3 million.

“It’s significantly higher in price because of that uniqueness, and emotional connection to the history of the house,” said Sanwar. “People are willing to pay because now [with NFTs] you can verify that it is in fact that item that is in fact that house.”

To translate that into the modern-day, there’s a boom in digital art being sold using NFTs. The buying and selling of digital art sits nicely in that “???” between making an NFT and profit. It also helps that these days you don’t have to code the whole blockchain to make a token.

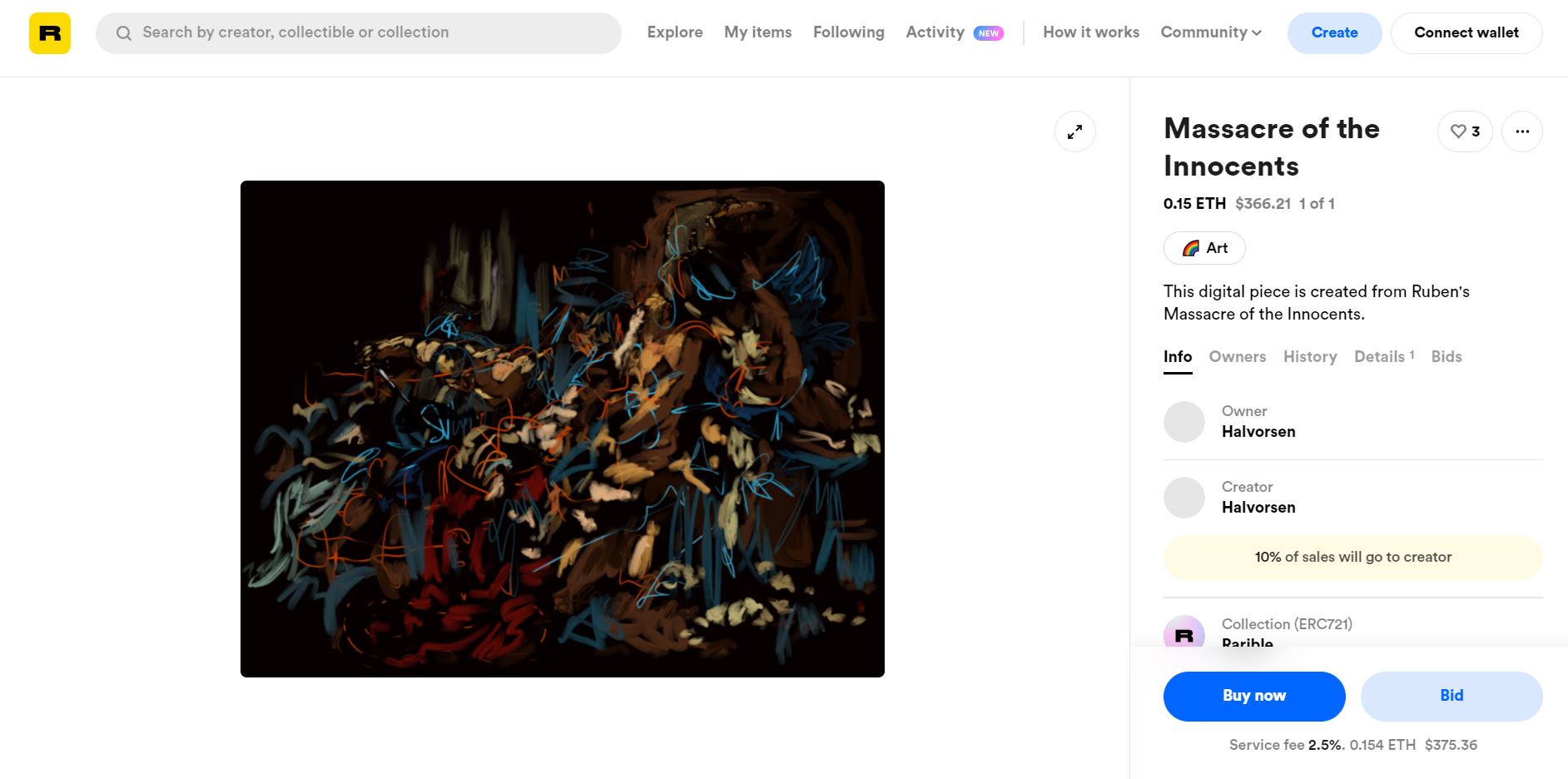

For Baltimore artist Tracey Halvorsen, the process of making an NFT involved about $100 worth of Ethereum coin, connecting her Coinbase wallet, then uploading her digital art to Rarible.

“They call [buying the Ethereum cryptocurrency] paying for the gas it takes to create the unique token associated with the piece,” said Halvorsen. “That price varies wildly depending on what the currency is trading for on that particular day.”

Now it’s possible to buy Halvorsen’s art for $366 or .15ETH.

It’s letting a lot of artists add value to their work in a way that still gives them ownership.

You might think you could acquire that art by right clicking and hitting “save image as,” or that she could send a copy of the JPEG on her iPad. But those options wouldn’t be worth anything. They’d be prints, as compared to the authentic, digital version, that’s verified by blockchain on Rarible for sale right now. I could download the digital version of her piece, called “Massacre of the Innocents,” a million times, and never be able to make a cent off it. But the NFT version will sell in perpetuity, and Halvorsen will get 10% of every sale that happens.

“It’s letting a lot of artists add value to their work in a way that still gives them ownership,” said Halvorsen. “[An NFT] authenticates that it’s a piece created by them, tracks the provenance, and really ties value to the piece in an interesting way.”