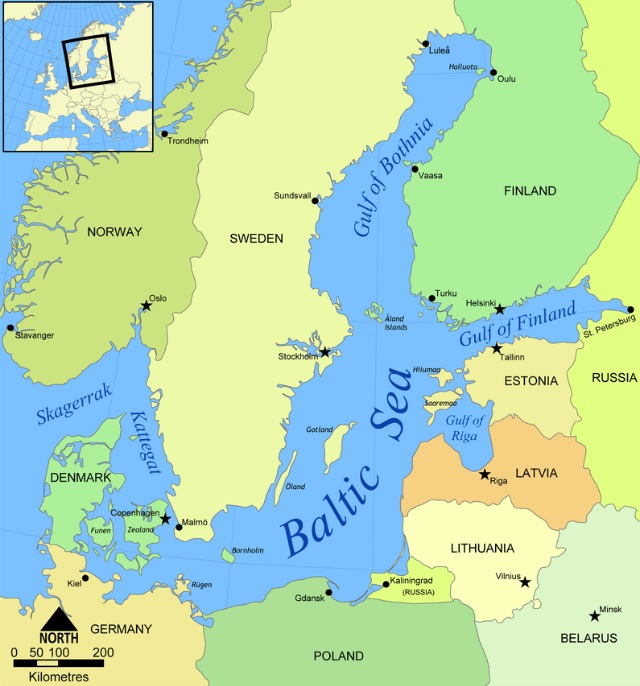

VILNIUS, LITHUANIA — Let’s get this out right away. Civic leaders here want you to know that Lithuania, the tiny country on the Baltic Sea, is part of Northern Europe.

That’s how the United Nations officially categorizes the country of 2.9 million. Last year, a flurry of local news stories in the Baltics — the region that includes Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — focused on how western media continue to nevertheless describe them as Eastern European. It’s a distinction that might not mean much to you, but it means everything to politicians, diplomats and business leaders in a region known as the Baltic Tiger for its rapid growth a decade ago.

To them, Eastern Europe is a clutch of stodgy, repressive, planned economies surrounding Russia. In contrast, Northern Europe is a region known for health and economic dynamism, more culturally West than East.

In many ways, they have that right. Lithuania, like its Baltic neighbors, is a member of the European Union, NATO and sports other signs of modern developed economies. Its two largest cities — capital Vilnius, a city of 550,000, and Kaunas, with 300,000 people — are regarded as genuine cultural and economic hubs. Business community leaders there speak breathlessly of the country’s surging information and communications technology (ICT) and life sciences sectors.

There are problems of course — notably post-EU brain drain, slowing economic growth, holes in its startup sector and the very tiny megaphone it is bringing to an increasingly crowded global innovation economy.

Despite, or perhaps because of that, Lithuania has plenty of lessons for small and mid-sized innovation clusters around the world.

Consider this a case study, sent from the emerging Nordics of Northern Europe.

###

You ever ask a man whose grandfather (and family) was sent to Siberia for owning a farm if he thinks his country has what it takes to make it onto the global entrepreneurship stage?

I managed to ask this of Danas Vaitkevicius inside a bustling coffee shop on German Street in central Vilnius.

Vaitkevicius is 40, ruddy-faced and serious during several conversations I had with him during a week I spent in Lithuania in December. He works in the exports and investments division of the Lithuania Ministry of Foreign Affairs, formerly stationed in Beijing and soon to relocate his family to Washington, D.C.

I was in Lithuania by invitation of his office. At Technical.ly, we’ve shied away from having members of our newsroom take funded reporting trips, for ethical considerations. But in my publisher role, charged with having a broad understanding of tech ecosystems and operating a small news organization with a limited budget, the circumstances felt different. So I accepted an offer from a member of the Lithuanian embassy in D.C.

I didn’t agree to write a story if there was no story. My questions weren’t limited, and I asked plenty of challenging ones. This felt like a novel way to add to our growing list of Technical.ly Postcards, in which we learn about the startup cultures of places we don’t typically cover.

So I traveled to Lithuania, letting the Foreign Ministry manage my flight and accommodations but accepting no direct compensation. In the course of a week, I met with 40 Lithuanians, including economic development and government officials, entrepreneurs and academics, most coordinated by the Foreign Ministry but all by my own request. I did my own research and asked my own questions, adding private time with others. I worked most closely with Diana Zarembienė, a chief public relations officer for the Foreign Ministry who helped coordinate those interviews.

Vaitkevicius was the first person she introduced me to, in a dark, gray, cold conference room of the Foreign Ministry building in Vilnius. It was fewer than 12 hours after I first landed in Lithuania, thanks to three snow-delayed flights. During our first meeting, Vaitkevicius was chockablock with facts and figures, starting our interview as stiff as the cold stone building we were sitting in. Until, that is, I asked him about growing up in Soviet-era Lithuania, before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

“We saw that system, we know what the past holds,” said Vaitkevicius. “That’s why we’re working so hard for what the future will be.”

The Foreign Ministry building is on historic Lukiškės Square, a pretty public green space — near where Soviets led a mass execution of Lithuanian separatists during World War II. Lithuanians, like their Baltic neighbors, have a complicated relationship with Russia. They regard the Soviet era as an illegal occupation that the rest of the advanced world ignored. In 1989, Lithuania declared the 1940 annexation by the USSR as invalid, presaging the looming collapse of the Soviet Union. During my time there, no fewer than four 30-somethings shared with me memories of spending hours in line waiting for the chance at a shipment of bananas in state stores. It’s easy to forget just how recently the U.S. was sending food aid to this beleaguered part of the world. So, no, they don’t take their identity or the future very lightly.

My PR handler Zarembienė and foreign ministry contact Vaitkevicius didn’t mind my asking about the repressive Soviet era. They just asked me for two things in return: make clear Lithuania has a very old, very inclusive history that goes beyond an occupation and, for goodness sake, don’t only focus on the past.

As Lithuania Foreign Ministry Deputy Director Dalia Kreiviene told me over coffee with her colleague: “Lithuania has so much to be excited about for our future.”

Around the world, places with brutal pasts — be it Soviet massacres or post-industrial blight — are looking to brighter futures. Here are some lessons Lithuania has for you.

1. Define your weakness as your strength

Savvy economic development specialists know an age old trick: Take what is perceived as your weakness and make it a strength.

Lithuania is a small, underdeveloped corner of the European Union, sandwiched between the advanced Nordic economies and Eastern Europe. You might think that means it’s easily forgotten. To Julius Norkūnas, that means Lithuania is an accessible, stable, cost-effective home base to access 500 million European Union consumers. It’s a subtle turn of perspective you’d expect from someone like Norkūnas, who is the head of the technology team for Invest Lithuania, a government-backed business attraction unit.

Being a low-cost talent center within the EU is not a dud of a pitch. Among the recent testimonials from foreign companies establishing offices in Lithuania, there’s Uber and Western Union and Wix.com and Barclays, among others. They have all grown offices where talent comes cheaply, and with high rates of multilingualism and education. Norkūnas and others gleefully noted that Lithuania has surged in recent years in global ease of doing business rankings, now better than Ireland and Germany. That’s meant Lithuania has attracted a cross-section of industries (transportation, financial services, media) with a similar tech talent pitch.

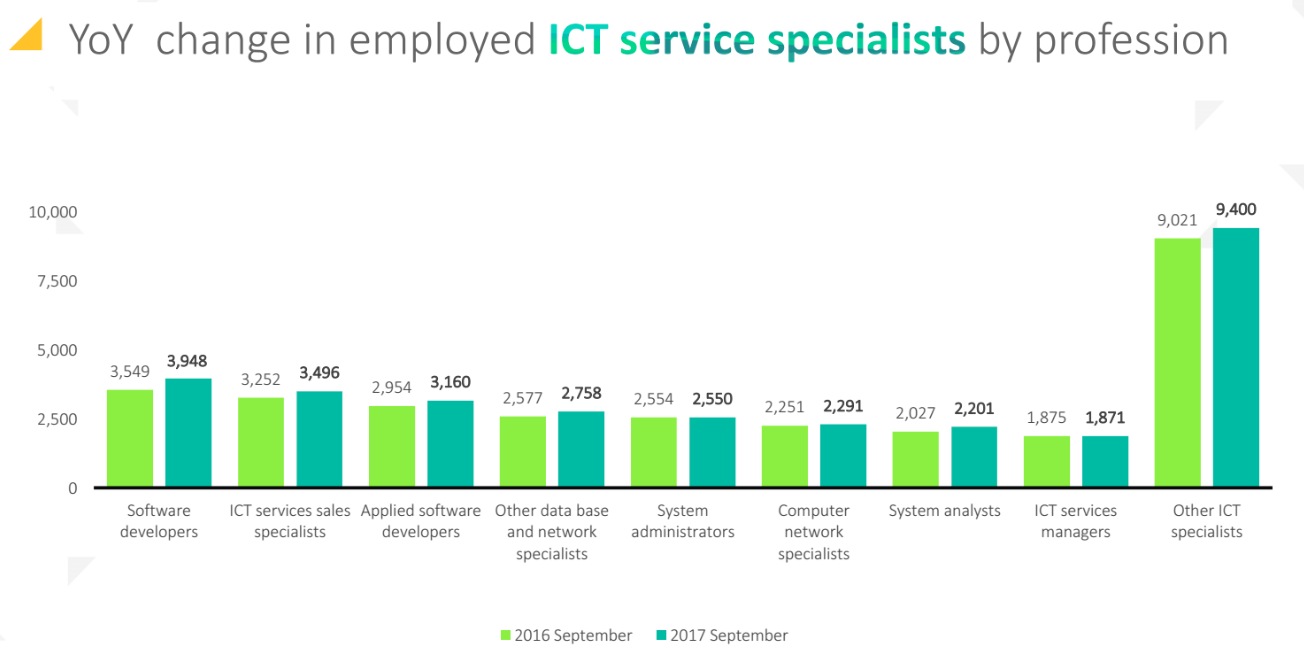

“IT is now officially a horizontal sector that impacts every industry in the economy,” said Paulius Vertelka, the friendly director of INFOBALT Association, a 160-member tech council in Lithuania. He lives in the data of the information and communications technology, or ICT, sector. The sector represented 3.7 percent of Lithuania GDP in 2016, a small but fast growing portion of the economy, particularly the more narrowly defined IT slice of that category, Vertelka said.

Though it’s a smaller percentage than Lithuania’s Baltic neighbors of Estonia and Lativa, his enthusiasm is coming from the speed with which the sector is growing. The $1.6-billion-USD sector in 2016 represented 148 percent growth since 2010. Now 28,000 Lithuanians are in the industry. From the first half of 2016 to the first half of 2017, there was 50 percent growth, the fastest rate in the Baltics, Vertelka said.

The country’s growth for now is being driven by characteristically bit players. Nine of 10 Lithuania tech companies have fewer than 10 employees, and fewer than a dozen have more than 250 employees. There’s a hope for more growth, particularly as Lithuania remains one of Europe’s largest net benefactors of EU spending, just a few years after joining the Euro Zone.

“How do we use that funding for the advancement of our digital economy?” asked Vertelka, noting a need for private-sector, risk-tolerant capital to transition from a long tradition of government reliance. “Right now it’s all in the West or with the oligarchs in the East.”

The attraction of outside capital needs more private-company success, he said. Several years ago, there was enthusiasm for developing a gaming sector, Vertelka said, but “fintech has the best chance of being the flag of Lithuania.”

2. Develop a specialty

If you’re someone who follows the development of tech clusters, you might know Lithuania’s neighbor Estonia.

That country, even smaller than Lithuania, has been hailed as having the most tech-savvy government in the world, for its early push for digital-first citizen engagement. That’s the heart of Estonia’s e-government focus, clustering startups and govtech companies that want to leverage that experiment lab for the future.

Lithuanians have plenty of love for their Baltic neighbors — and plenty of competitiveness, too. So Lithuanians have taken to establishing their own speciality. Lithuanians are throwing their hat in the ring for fintech.

Perhaps nobody is selling harder the idea that smaller is stronger than Marius Jurgilas, the economist and former European Central Bank researcher who became a board member of the Bank of Lithuania in 2013. One founder I spoke to lovingly called Jurgilas — just 38 — serious, self-assured and deeply proud of his accomplishments, “Lithuania’s godfather of fintech.”

For a country this small, the Bank of Lithuania is something like if the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, the SEC, FDIC and other anchors of the American financial system were all housed in one place, Jurgilas proudly notes during an interview in his office. That’s allowing Jurgilas to push forward an idea for Lithuania to become friendlier to financial innovation than anywhere else in the world.

The Lithuania government just closed its open call for feedback on developing its own financial “regulatory sandbox” — a growing global concept of creating exceptions in financial regulation from fines and prosecution. The idea is that a company could release, say, a payment platform that users could opt-in to use, without any risk of fines if the platform would fail.

The idea of “regulatory sandboxes,” are increasingly popular — more than 20 are in the process of being legislated. The United Kingdom (and London specifically) is largely credited with introducing the idea. But Jurgilas thinks Lithuania has exactly what is needed for the most advanced one yet.

Just this month, the Bank of Lithuania announced a blockchain-focused sandbox plan. Jurgilas expects legislation to be finalized this year.

“Basically the banking and financial system here started from zero 25 years ago,” said Ilya Laurs. “There is such thing as the late-mover advantage.”

Like Jurgilas, Laurs, handsome with the beginning traces of gray hair, is among the brightest lights of Lithuania’s innovation economy. So it matters they’re both leading the charge toward fintech.

Laurs founded GetJar.com, an Android app store that was at one time seen as a genuine rival to the Apple App Store for global marketshare of mobile app purchases. The company became the crown jewel of Lithuania’s consumer facing tech crown, before being acquired in 2014.

Laurs now works as the chairman of Nextury Ventures, something like a venture capital company but with a co-building model that appears familiar in Lithuania’s still quite young early stage private equity sector. Over the last 15 years, Laurs has traveled between Silicon Valley, European financial capitals and his native Vilnius. Familiar with the challenges of growing consumer companies in a tiny country, he is now keen to specialize on a wonky sector.

“There is something very different about a large open economy and a large closed economy and a small open economy,” he said. The financial industry will be most transformed in small open economies, like Luxembourg, Singapore, the Scandanavian countries and, yes, he hopes, Lithuania, where experimentation and possible. Sandboxes, after all, are typically rather small places to play.

“The financial industry will never be truly changed inside the United States,” he said. “We’re declaring a fintech innovation priority here.”

3. Get universities to invest in entrepreneurship

When colleges want to show off the employment rate of their graduates, the idea of throwing their students out into entrepreneurial ventures can seem worrisome.

Startups are notoriously volatile, of course, and being an early-stage founder can often sound mysteriously similar to unemployment. But with their hubs of resources, intellectual discovery and collision of ideas, universities have always been anchors of innovation districts. Though Lithuania’s historic Vilnius University, with origins in the 1500s, is a major educator of the country’s elite, second-city and former capital Kaunas has an outsized reputation as a college town with a new wave of arts and culture.

The Kaunas University of Technology, with 10,000 students, including several hundred in Ph.D. programs, is a primary example of that. Around large-scale public art and new research facilities funded in part of by EU cash, a startup cluster is booming.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=acrhvhMqTdU

In last five years, 60 companies have formed at the KTU Startup Space incubator, said Arūnas Lukoševičius, a professor and scientific supervisor at the school.

They include the Food Sniffer, a wireless device to check for freshness of meat based on research from a food science and chemistry professor (and with quite a, uh, colorful marketing campaign), and Parksol, a system to manage parking garages by tracking open spots via sensor system.

The young KTU undergraduates who are building Glucocare, a non-invasive Diabetes monitoring, earned the chance to represent the Baltics at the forthcoming 1776 Challenge Cup in Washington, D.C., this year.

Others are even further down the entrepreneurial journey. KTU research is behind medical device company Vittamed, which raised $10 million in financing in 2015, and Rubbee, which first caught international attention in 2013 for its approach to adapting any bicycle into an electric bike. Last month, it tripled its latest Kickstarter goal, launching a new kit.

“You can buy one now,” Gediminas Nemanis, the smiling, young Rubbee cofounder and CEO, said to me, laughing off his own eagerness to sell. I met him at a startup showcase inside Žalgiris Arena, the home of Kaunas’s celebrated basketball team. Around him were a dozen other founders, in addition to the researchers and economic development leaders who want people like him to thrive. “There is so much support,” Nemanis said.

4. Cluster your early experiments

Beyond universities, any good tech hub has more clusters to share resources and attract more experiments.

The coworking community is nascent here — just a handful of organic gatherings of independent technologists share space so far. But the economic development-minded efforts are there.

“Economically, philosophically, politically, geographically having people with different functions and styles sit in the same place just because who pays their salary doesn’t make sense,” said Laurs of Nextury, who says he’s courting a big global coworking brand to Vilnius to drive forward the density of knowledge workers.

In addition to the Barclays-backed Rise Vilnius fintech-oriented coworking space, the unique Vilnius Tech Park, with some 27,000 square feet of office space across a handful of historic buildings outside of city center, is among the country’s anchors for colocation. Its tenants include an array of consumer brands whose staff interact in the hallways and sidewalks.

Look at Deeper, a fast-growing outdoor-hardware tech company that is focusing on the American market with its first product, a fish-finding sonar device, and plans for more.

“We want to be Apple for the smart outdoor products,” said a Deeper staffer. “This is something we can accomplish from Lithuania.”

Strolling the tree-lined paths of the Vilnius Tech Park, with a gentle snow, conveys the value. Though many there do drive to the Tech Park, others walk, use transit and a few are just beginning to look toward bicycling. Like tech parks elsewhere in the world, resources are shared, events bring people together and the companies feel they are stronger together.

There are 35 employees at CGTrader, a 3D-file marketplace, inside a high-ceilinged, second-floor, three-room office, said the company’s head of marketing Ginvile Ramanauskaite. “This is a place we want to be,” she said.

It certainly makes the talent attraction offering easier, as employees have several dozen growing and interesting companies to choose from.

Lithuania policymakers want to see more examples like Planner 5D, a consumer-friendly architectural drawing and room layout product founded by a pair of Russians. Cofounder Alexey Sheremetyev is using Lithuania and the Vilnius Tech Park as part of his company’s expansion strategy. Half of their 20 person team is there, the rest in Moscow.

Sheremetyev wanted to be closer to the western markets, both Europe and the United States, and saw Lithuania, which has lots of Russian-language speakers and even more with English skills, as an ideal transition point.

“We can get business done here,” he said.

5. Make your cities great places to live

In Kaunas, talk of tech and economic incentives is mixed in effortlessly with public parks and public art.

At least if you speak to Deputy Mayor Simonas Kairys, it does.

He came to Kaunas as a young university student. Now he’s pushing forward an array of cultural strategies that he sees as deeply linked to the future of both his adopted city and his native country. One of his initiatives is Startups of Kaunas, begun in 2015 as an annual grant making strategy to young companies. So far, the program has gifted an average of $20,000 USD without longterm residency requirements for projects at the idea phase.

“After two years, they might collapse, but that’s not our focus,” said Kairys, seeming somewhat shy but not unconfident, in his office. “In Lithuania, we lack a culture of making something big from something that is small.”

In 2018, Kairys, aided by Tadas Stankevičius, the head of the city’s Business Division, hopes to transition the grant program to a startup liaison initiative to match young companies with existing resources. Though he has an interest in the high tech efforts spinning from nearby universities, Kairys notes his city needs a diverse array of businesses, including the cultural amenities that make cities great places to live.

“We are making Kaunas brighter and greener and smarter,” he said.

That sentiment is a major part of Lithuania’s strategy. Like much of the United States, the country’s more rural areas and smaller towns and cities are largely facing economic decline. The country’s successes are largely consolidating, said Inga Romanovskienė, the recently promoted director of Go Vilnius, the city’s tourism and business attraction unit.

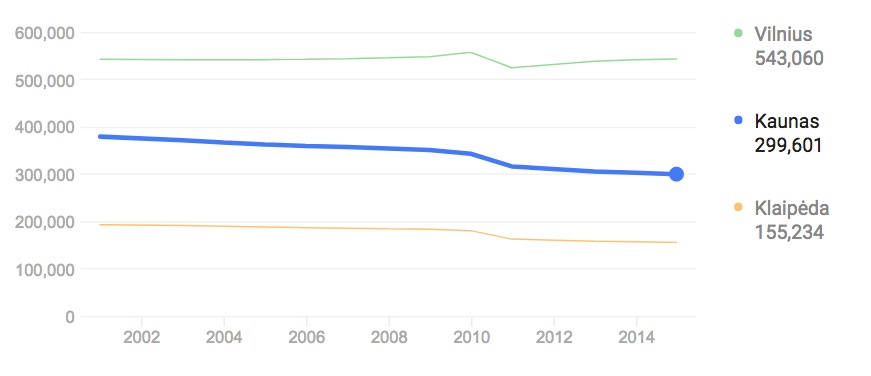

“Where other places in Lithuania may struggle, Vilnius is thriving,” she said. To be clear, for all that is very much working, even Vilnius has only, at best, stabilized its population. Second city Kaunas and the seaside port city of Klaipėda, the country’s third-largest, are both declining in population. Like its Baltic neighbors, Lithuania is about the same population size as it was in 1960 — 2.9 million residents. The country loses residents abroad — more Lithuanians live in the United States than Vilnius — and is aging. That could be a problem.

So like the idea of tech and innovation, most I spoke to say that Lithuania’s future will rise or fall with the fate of its two largest cities. It follows then that there’s considerable attention paid to where its young leaders are headed.

A country as small and educated as Lithuania has a reputation for sending its best and brightest abroad for either university or early work experience. But the aim is to bring them back, particularly now to their two urban centers.

In November, a team of undergraduates from Vilnius University took the top prize in iGEM, a celebrated international synthetic biology research competition. It’s the kind of place where 20-somethings who choose lab work over partying come to compete.

I spoke to four members of Lithuania’s winning team inside the small library of the tony Stikliai Hotel, where American diplomats like Hillary Clinton, Dick Cheney and Joe Biden have stayed. All four represented a trend among brainy elite Lithuanians that many are praying will come true.

All four planned to study abroad and, crucially, also all said they plan to come back home to Lithuania. They all also noted a preference for the academic path, over bringing research to the marketplace but Gabrielius Jakutis, polite, whip smart and handsome, noted he follows word of a growing tech community.

The native of Vilnius said: “What we most want to see is more options for making a life here at home.”

6. Start your local investor community with impact

Like anywhere, the business community here is built on its past.

In 1986, Alvydas Zabolis was in his mid 20s, studying at Vilnius University under Soviet rule. A year prior, then new Soviet Communist Party leader Mikhail Gorbachev announced a series of policies called Perestroika, or “restructuring,” including economic reforms, in response to the planned economy’s stagnant growth. It was the very beginning of a modern entrepreneurial climate, and the Soviets were eager to find a Communist-style high tech commercialized success. Bright young Zabolis was among their bets, charging him and a team of graduate students to sell a laser to the East German government.

“The Germans bought our laser because the Soviets told them to,” said Zabolis, laughing. “But we were all very proud.”

Zabolis became an entrepreneurial star in a new business climate that surged in the 1990s. By 2002, he launched Zabolis Partners, one of Lithuania’s first Western-style private equity firms. Though the company has focused mostly in real estate, younger partners like Algirdas Baltaduonis are eager to see more high growth tech to follow that early photonics example. They see that work both as a way to make a lot of money and have a considerable positive impact on Lithuania.

I met Zabolis, dressed flawlessly in a fine suit and tiny round Euro-style eye glasses, and Baltaduonis, with a big brown bowl cut of hair, over lunch at the Vilnius Club, a once-decaying mansion in the city’s Old Town that is now the start of something different. In recent years, the group’s members have been fixing the mansion up, allowing for the age to show in the building’s gorgeous, if faded, ballroom.

“We have a lot of work to do,” said Zabolis, who is the group’s chairman. “But we want to show the age so we don’t forget the history that brought us here.”

Their cheering for Lithuania will be familiar to any early tech hub’s investor class. Other bright lights are still developing.

There is the blandly named Angel Venture Fund, which has been operating since the mid-1990s. Much of its co-investment activities in recent years have been done in partnership with government funding via the European Union, and the lines between investor and founder are far blurrier than in the United States.

“I’m not a fund manager,” said Arvydas Strumskis, belying his business card, which does, in fact, list him as a fund manager. “We’re building companies.”

As he speaks in his conference room near the Oracle offices here and not far from where a 30-person tech team for Uber sits, he shares highlights from his 29-company portfolio. One of them is an online rent-to-own alternative with a drop-shipping ethos called Be Kredito (“No Credit”) that he said did $700,000 in sales in 2017. Another is micro-laser company Integrated Optics, which boasts De Beers as a customer and is part of a “pocket of resistance” in lasers.

“We even just started using the term of ‘ecosystem’ just four or five years ago,” he said. He says he has a 100-person active angel investment network and that has many as 1,000 people have made investments. “Things are still fragile.”

7. Understand your challenges

Though we set the ground rules before I traveled, knowing its turbulent past, I arrived unsure of how truly open Lithuania would be.

One of the clearest prerequisites for a thriving innovation economy that most Americans take for granted is serious and open intellectual debate.

In the United States, we reserve the most challenging questions for our leaders. Would Lithuania be the same? My first morning in Vilnius was with those Foreign Ministry diplomats inside a government building, seated next to my government-issued handler. I asked them about Lithuania’s slowing rate of growth and declining population. Nobody blinked. If anything, they were more able to articulate their country’s challenges than a foreign journalist with little experience in the Baltics. Crucially, though, they were also able to articulate their country’s vision for something different.

Invest in advanced research and education. Court educated Lithuanians abroad, grow trade partnerships abroad. Push and celebrate entreprenuership and the high-tech sector. No country ever grew by blind desire for long. It takes consensus and culture. To get there, a city, a country, a people need to wrestle honestly with challenges and opportunities.

Let the ideas compete and thrive.

Lithuania wants you to know they’re open for business, that they already have a track record of some very global brands hiring and growing here, that their biggest cities have educated and multilingual and friendly workforces. The country is looking to the best of Europe, wanting to carry the mantle of globalization, though as one government official told me on background “we’re still wrestling with the Soviet bullshit.”

Eating dinner with three tech startup sceneters at buzzy Ertlio Namas restaurant, which specializes in traditional Lithuanian fare through hundreds of years of history, one, Taurimas Valys, who knows American startup communities well notes how early Lithuania still is. Many American cities are still new to the second wave of founder culture born of Silicon Valley, Valys correctly noted, so things like venture capital and an entrepreneurial technical workforce are still rare.

But everything hopeful about Lithuania is in these conversations, he added.

Lithuania’s growing IT tech workforce still remains largely generalists, noted Laurs, the Nextury and GetJar.com entrepreneur. The advantage is that they come at a cheap price, particularly by EU standards, hence the country’s impressive corporate cluster, but growing startups may face “a structural problem” when they aim to build a cohort of technical specialists. There’s a Code Academy in Vilnius and changing university curriculum but their numbers remain slow.

Laurs is instead more excited by early rumors of technical talent that might spinout of those corporate players and launch their own startups. He isn’t anyone who wants to force colocation, he’s a techno-optimist type who wants free movement of people and ideas. But he knows his decision to stay rooted in Vilnius over Silicon Valley is something his country needs more of. His people have been proudly trying to live independently while welcoming and working with others for hundreds of years. A tech cluster won’t just appear without a lot of effort from many people and groups.

Sound familiar?

“Nobody is willing to innovate in a garage anymore,” he said. “Success is way more about the ecosystem than an individual company.”