For the immigrants served by the Southwest Philadelphia-headquartered Coalition of African and Caribbean Communities (AFRICOM), health inequity doesn’t just look like the false stigmatization of immigrants as COVID-19 super spreaders or lessened access to food benefits programs — though it looks like those, too.

There’s also a cultural barrier to accessing care, especially during the pandemic, when in-person service is limited and telehealth has become the norm.

“Culturally, people continue to love one-on-one conversations and seeing the face of a medical doctor” in person, said Eric Edi, Ph.D., the executive director of AFRICOM.

These are among the social determinants that have led to disparities in healthcare for communities of color amid COVID-19.

Health equity — the state in which all people can achieve their “full health potential” regardless of “social position or other socially determined circumstances,” per the Centers for Disease Control — is not a buzzword, but a common goal for those working at the intersection of healthcare and technology. That’s especially true for communities of color who are more likely to live in poverty and see unequal healthcare outcomes. (For instance, according to Penn Medicine research, the maternal morbidity rate in Philly neighborhoods increased by 2.4% with each 10% increase in the percentage of Black or African American people in a census tract.)

The pandemic has forced people of all backgrounds to assess their relationships with the healthcare system. For Americans with health insurance and access to a smartphone, shifting from in-person doctor appointments to virtual telehealth meetings was relatively easy. But for those lacking digital tools and resources, it has made seeing a physician vastly more difficult.

Individuals living 100% below the poverty line have significantly worse health outcomes and lower life expectancies than those living 200% above the poverty line. They are more likely to develop coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, stroke and other ailments.

At the same time, access to digital tools can be more limited — which means access to healthcare resources like telehealth is also limited, at a time when 87% of Americans have considered the internet to be important or essential.

They’re issues local founders and institutions are working on. Cayaba Care’s Dr. Olan Soremekun, for instance, is using tech to bring healthcare to communities with low access in an effort to improve mortality rates among Black women giving birth. LucasPye Bio’s Tia Lyles-Williams noted the systemic inequities in biotech and is looking to remedy the issue by helping more Black people enter the industry, while also advocating for pay for diverse medical research participants with the forthcoming HelaPlex. Center City-headquartered insurance giant Independence Blue Cross just hired its first-ever executive director of health equity in Dr. Seun O. Ross, and Johnson & Johnson is funding entrepreneurs with solutions in health equity via its new Health Equity Innovation Challenge.

Over the past few months, Technical.ly has spoken to more than a dozen experts ranging from physicians to researchers to startup founders about the factors that have led to health inequity for marginalized communities, as well as what can be done to fix it. For this first of a multi-part series on the intersection of health equity and technology, Technical.ly spoke to health-minded leaders about the ways in which they’ve seen vulnerable populations impacted by health inequity, and possible solutions moving forward.

One big barrier: According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 47% of non-citizens living in America do not have insurance. That means immigrants, in particular, may have a harder time accessing healthcare than other groups.

AFRICOM is a 20-year-old coalition that supports African and Caribbean immigrants through the likes of immigration policy advocacy, health literacy programs and leadership training. Many immigrant families Edi works with deal with a language barrier that keeps them from accessing health resources, as do concerns about saving money out of necessity versus going to the doctor. Mental health is a concern, too, as they may be hesitant to pursue therapy due to not having done it before moving to the U.S.

“With the immigrant community, we talk more about trauma and mental health,” he told Technical.ly. “The ways in which mental health is defined over here is not the way it’s defined by African immigrants and they’re seeing it under a different light and that may lead them to not seek services that exist.”

Edi opposed former President Donald Trump’s Public Charge rule, which kept many immigrants interested in emigrating to the United States from attaining healthcare resources before being repealed by President Joe Biden. Many immigrants Edi served during the Trump presidency who would have otherwise been eligible for public benefits like Medicaid or food stamps were limited by the policy.

“The system we operate in is another dimension [in terms of] racism, white supremacy and [a barrier to] access to services,” he said.

Research on job access and insurance rates in the United States reflects Edi’s experiences. Low labor force participation and a lack of career-sustaining job opportunities puts many people of lower socioeconomic status, including immigrants, on a dangerous trajectory in managing their health.

“Largely, healthcare in the United States is employer-based, so if you have a good full-time job, you have access to healthcare,” Economy League of Greater Philadelphia researcher Michael Shields said. In Shields’ work, he uses data and research to clarify why certain issues matter or in which ways they affect communities.

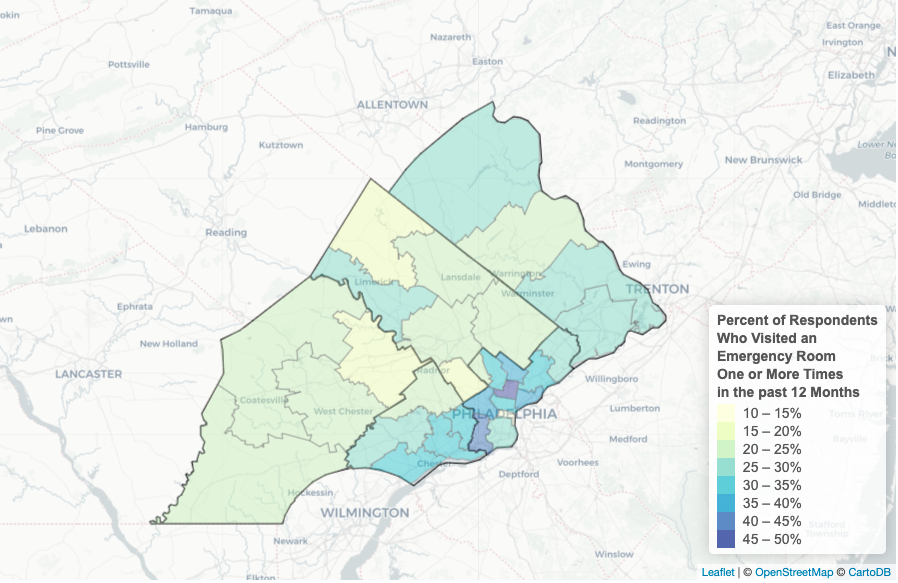

According to Shields, increased emergency room visits correlate with levels of low employment in communities. Shields finds that people who lack access to affordable healthcare — because their jobs don’t offer it — may only prioritize healthcare when they’re facing a medical emergency. And without insurance, they may need to pick between paying for the medication they need or recurring expenses like rent.

Shields has noticed a greater emphasis in preventive healthcare over the last decade. For families in which asthma is prevalent, being able to track it earlier can bode well for a healthier lifestyle. But prevention still cannot compensate for fundamental barriers to access.

“Understanding family health history is preventative care,” he said. “The problem that remains is still a gap in equity and inclusivity for Black and brown populations. Eventually, someone has to pay the bill. Closing the gap would be offering free or public services.”

Unless the system is rebuilt, Shields believes that people will continue to suffer if they don’t have jobs that provide access to adequate healthcare.

“The way the system is set up, you need a job to get good healthcare,” Shields said. “If we have to play the game this way, you have to offer quality employment opportunities. To change that would be upending the [current] structure.”

Dr. Ruth Perry agrees with Shields. When she began her medical career, the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion didn’t exist — and if someone did have Medicaid, access to healthcare was still limited, and there was no access to affordable mental health resources at all. While the healthcare system has improved since then, she said, she still believes gaps in access prevent certain communities from gaining the healthcare they need.

Perry, a Swarthmore College alum and member of Ben Franklin Technology Partners’ Healthcare Investment Group external review committee, worked as a physician in Central Harlem during the pandemic and saw the impact of COVID-19 on communities of color firsthand. Black people of backgrounds ranging from African to Caribbean descent lined up blocks around the corner from the clinic where she worked each day, she told Technical.ly. Multiple access issues converged during that time to create an even bigger obstacle for the communities she worked to treat and serve.

“The other thing you saw concentrated in New York [was] there was so much congregate and multigenerational living with people in duplexes or in small apartments,” she said. “It was hard for people to isolate because of the housing infrastructure. That made it easier for the virus to spread [because of] the density of people in NYC and housing availability. Early on, it was difficult to get people to isolate. It increased the disease burden in NYC.”

Public transportation was often the only means lower-income people of color had to get from outer boroughs to their testing sites, she said, which underscored the need for another way for patients to get treatment during a time when people were asked to socially distance.

For individuals who do have broadband access, telehealth can connect community members who may not be able to get to physicians or clinics to those resources. She believes it works along with other social health determinants as a way to facilitate patient and physician communication.

Telehealth “worked in big teaching centers and some in communities,” she said. Due to the new costs of operating telehealth, many clinics serving under-resourced committees did not provide it as an option, forcing patients to make difficult decisions, Perry said. “It’s expensive to set up telehealth. That drove those patients to urgent care because they were too afraid to go to hospital emergency rooms.”

Providers also need technology on their side to execute, Perry explained, and when made available, she has found it to be helpful for community members more in tune with current tech trends. She is concerned that older members of the community, particularly ones with less education, won’t be as adept at using telehealth.

Back in Philadelphia, what we commonly call Southwest Philly encompasses neighborhoods such as Kingsessing, Paschall, Bartram Village, and Angora, as well as Grays Ferry. The area is majority Black — both African American and African immigrant — and the rowhome-lined neighborhoods are underserved when it comes to healthcare. In Kingsessing-Paschall, for example, there are 3,590 residents for every physician; the city average is 1,460 per physician, according to Generocity’s reporting.

And then there’s the digital divide, and lack of digital literacy, that have also long been issues in the Southwest. The CDC says that restricted access to technological devices such as cell phones, tablets, and computers may make the practice of telehealth challenging.

Meanwhile, in Paschall Kingsessing, according to a map of broadband subscriptions compiled by Comcast in 2019, 39% of households do not have broadband internet. And it’s worse in other parts of the Southwest: In Kingsessing it’s 42%; in Grays Ferry, 46%; in Bartram Village, 52%.

“In addition to the lack of basic computers for many, there is the culture of ‘in-person’ appointments with doctors, which makes people feel more secure and cared for,” Edi told Generocity last year. “But, still, I do not think that we should shy away from telehealth completely. Digital literacy is a must-have skill. The same as we invest in language and English classes, we should invest much more in digital literacy classes.”

While Edi appreciates the access telehealth has provided some users, he’s found that for many immigrant families without access to broadband internet — and those who are more comfortable with in-person conversations — the method is not effective.

As Biden continues to champion the infrastructure bill aiming to drastically expand broadband access, Perry is hopeful that health equity and its relationship with tech will be prioritized in policy moving forward.

“If the infrastructure bill from the federal government goes through, President Biden wants to put in wireless hotspots, but being able to tie broadband tech to health and health equity would be really important,” she said. “I think that we need tech to play a role in helping promote true health literacy in our society because we don’t have it. Even the things we learn in health [class] in school, that’s not enough.”

Health equity for people of all backgrounds means universal access to resources ranging from high-quality internet to jobs providing health benefits. It also means supporting immigrants with different cultural traditions as they find a new life in America. Without changes to our healthcare system, these experts say, the equity gap will only get larger instead of getting smaller.

_

The next parts of this series will take a look at how Philly startups are tackling the health equity gap for Black and brown communities in need of healthcare, and what the future of health equity solutions could look like.