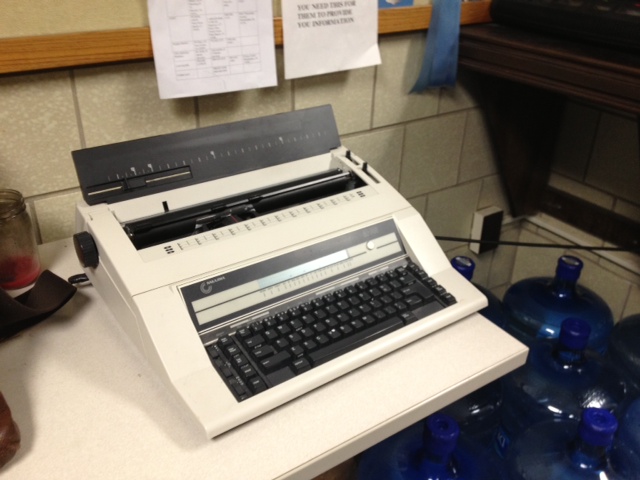

On any given day, you can find a Philadelphia cop clacking away at a typewriter. He might be a detective writing a search warrant, or she could work in the Narcotics Unit and be writing a report about the drugs she just confiscated.

It’s just another part of the job.

Right now, Philadelphia’s cops use typewriters to write two kinds of reports: property receipts, which must be filed when an officer takes any object off someone, and search warrants. Cops have to use typewriters for these tasks because the reports are pre-formatted and numbered to keep track of them and to protect against fake versions. The reports must be fed into the typewriter or handwritten. In simpler terms, the cops just don’t have a system to replace this one.

But not for lack of trying. The cops were supposed to have a new system years ago, a system that would digitize all the typewriter-generated reports and make the department worlds more efficient. The city has been waiting 10 years and has spent more than $7 million on this proposed system, so why are cops still using typewriters?

Philadelphia’s police department isn’t unique in this regard. In 2009, UPI reported that New York City was working on a system to upgrade the NYPD‘s police software but, in the meantime, was spending nearly $1 million on new typewriters.

This also isn’t to say that the Police Department is stuck in the dark ages. It has an electronic system for its arrest warrants, an electronic evidence management system and a brand new GIS mapping and crime analysis system [check back later this month for a story on this]. Technically Philly has regularly covered the department’s use of web communication for earning leads on cases. As the City of Philadelphia goes, the Police Department is often seen as among the most embracing of IT upgrades.

“We’re lagging behind in one small area,” said police spokesman Lt. Ray Evers about police IT.

The department is lagging behind in this area because Philadelphia police officers, like others in the country’s biggest cities, are still doing some of their most common and important administrative tasks on a communication tool that was first innovative in the 19th century.

A brand new system

It all started with the mid-1990s 39th District police scandal, one of the worst police corruption scandals in the city’s history. Several civil rights organizations threatened to sue the city, but the city agreed to several conditions and was able to settle out of court.

One of those conditions was to computerize several types of records, as the Daily News reported in 1996. A federal judge would watch the department closely and make sure it was getting a new, digital system that would increase transparency, according to a Philadelphia Inquirer article from that time. That meant the Police Department was under a lot of pressure to deliver, and quickly, at that.

Some city contracts are stuck in the past

If you want to look at a city contract, you’d better hope the city has an electronic copy of it. Otherwise, you’ve got two options: pay up or head down to the Law Department to look at it yourself.

That’s what happened to Technically Philly when we requested the city’s contract with IBM for the police department’s IT upgrades. The city told us that we either had to pay $72.25 to get a copy of the 289-page document ($0.25/page) or go down to the Law Department to review it. It’s not unusual for the city to only have hard copies of its contracts, said Open Records Officer Jo Rosenberger-Altman.

Following recommendations from an investigative committee, in 2002, IBM won the $4.7 million contract to computerize the department’s records, according to a Technically Philly review of the contract. IBM would develop a system that would automate three kinds of records: investigative reports, filed during every criminal investigation, property receipts and search warrants.

It would mean the end of typewriters for the police. It’d also mean no more wasted time on redundant data entry, no more worrying about paperwork getting lost, no more hoarding stacks of paper reports for court. The whole project was supposed to take 30 months, said Police Department project manager Tom Olson.

The ten-year effort

The trouble started immediately.

IBM hired a subcontractor to carry out the contract, a Salt Lake City, Utah-based company called CRISNET. (Today, another unrelated Salt Lake City firm, named Public Engines, manages the police department’s online crime data map.)

Soon after the contract began, the city realized it bought the wrong product, Olson said. It wasn’t a case management system that would allow police to digitize its records. Instead, it was a crime reporting tool. CRISNET was a small company, so it had a rough time customizing the system on the fly, Olson said.

CRISNET successfully launched one part of the system in 2004, which Olson called a major victory for the department. It digitized the process that the department uses to generate some 250,000 investigation reports filed every year. In 2009, CRISNET also implemented a system that allowed cops to send relevant paperwork to the District Attorney’s office through a digital system. This was another success, Olson said, since before, cops had to hand-deliver paperwork to the District Attorney’s office and worry about important documents getting misplaced in the process [find our story on this system here].

That’s the extent of the contract’s direct success, said those interviewed.

Project manager Olson, his team and global IT consulting firm Ciber, which had also been retained, were unhappy with the rest of CRISNET’s work and never implemented the property receipt system, though it had been finished, he said. The search warrant system was forgotten.

Still, the city renewed this IBM contract multiple times from 2004 to today so the vendors could do maintenance and to push the project forward, said Lt. Fred McQuiggan, who has worked on the project since it began. Since the contract had a fixed price, scrapping it would cost the city more money in the end, McQuiggan said. IBM had also already built parts of the system that would be lost if the city had ended the contract.

The extensions did not cost the city extra money because of the fixed price, but the city did pay consultant Ciber roughly $20,000 per month for its decade’s worth of work on the project, McQuiggan said, putting the total price of the project at roughly $7.1 million. It’s important to note that the city did not pay IBM for any part of the project that it did not complete, Olson said. [Updated, see below]

So, after ten years and $7.1 million, what really went wrong?

Endless back-and-forth between the city and the contractors, on needs assessment, analysis and user testing, among other normal development processes clogged by bureaucracy. Different administrations came and went (Ed Rendell was mayor when the police corruption scandal broke, first pushing forward interest in digital record keeping and greater transparency. John Street was mayor when the contract began, and there have been three police commissioners since that time, not to mention the initial creation of a director of Police IT position in 2006 [find our story on that here] and multiple attempts at consolidating city IT processes. CRISNET was acquired by Motorola halfway through the project, which brought even more decision makers into the process.

When asked for comment, IBM spokesman Michael Rowinski said that IBM is working with the city to “develop and deploy solutions that provide its police department with the modern tools it needs to protect residents and visitors,” adding that IBM is building “additional enhancements which can add value to the [project’s] ongoing success.”

Olson thinks the city and the vendor underestimated the project. The Police Department had no experience doing anything like this, Olson said. He also thinks the pressure from the courts following that corruption scandal didn’t help.

“We were not driven by business needs solely,” he said. “We were driven by what was going to get the judge off our back.”

What’s next

The city is still in negotiations with IBM and cannot comment on the contract, said Deputy Police Commissioner John Gaittens, who has overseen the project. It’s still unclear if the city will implement CRISNET’s property receipt system. As for the search warrants, detectives will have to wait for a new system. For now, the typewriters will stay.

Read the next story in our series here. It’s about how police leadership, specifically one deputy commissioner, changed the way cops do their jobs by introducing new technology tools in the ’80s and ’90s.

Updated 11/12/12 4:37 to clarify that the city did not pay IBM for any part of the project that it did not complete, according to Olson.