Few things can make humanity seem as small and defenseless as hurricane season. With all our technology, we can’t stop or reroute a storm. What we can do is monitor the ocean for hurricane activity, using the data to make predictions that can save lives.

Most of us are familiar with using satellite imaging to track storms, but there is another method that’s a bit more Pacific Rim — the ocean is monitored by underwater robots called Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUV), which collect data and help detect potentially disastrous storms (among other things). They look like this:

Delaware is less of a hurricane hotspot than the southern states, but it’s located right in the middle of the most densely populated coast in the country: the ominous-sounding Mid-Atlantic Bight, which stretches from Cape Cod, Mass., to Cape Hatteras, N.C.

The Mid-Atlantic Regional Association Coastal Ocean Observing System, aka MARACOOS, was born in 2004 as one of 11 regional associations in the U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System. Headquartered in Newark, Del., MARACOOS launches UUVs that monitor the entire Mid-Atlantic Bight.

“[It’s] about 600 miles,” said MARACOOS Executive Director Gerhard F. Kuska, “including five urban bay/estuary systems, including Chesapeake Bay, the nation’s largest; the largest naval base in the world, Norfolk Naval Station; a quarter of the U.S. population, and important transportation hubs, fisheries, tourism, and a big offshore wind resource.”

So how do UUVs, commonly called gliders, detect potential hurricanes?

Rob Nicholson of Lewes, a tech entrepreneur and oceanography officer in the Navy Reserve who works on UUV projects for the Office of Naval Research, explains: “They can collect and transmit real time data to forecaster and numerical models to aid in predicting hurricane intensity based off of ocean temps.”

Or, to put it simply, UUVs detects warm ocean water, and “warm ocean water helps fuel hurricanes,” he said.

“The Navy is working to develop a UUV ‘mothership’ that could launch a team of small UUVs,” Nicholson said, adding to the program’s air of science fiction.

But really, UUVs are just another way to use robots to do tasks that are risky for humans. The Delaware State Police has bomb-diffusing robots and uses aerial drones to investigate crimes; DEMA uses drones for environmental mapping and search and rescue; and the Delaware River and Bay Authority uses drones to inspect the Delaware Memorial Bridge.

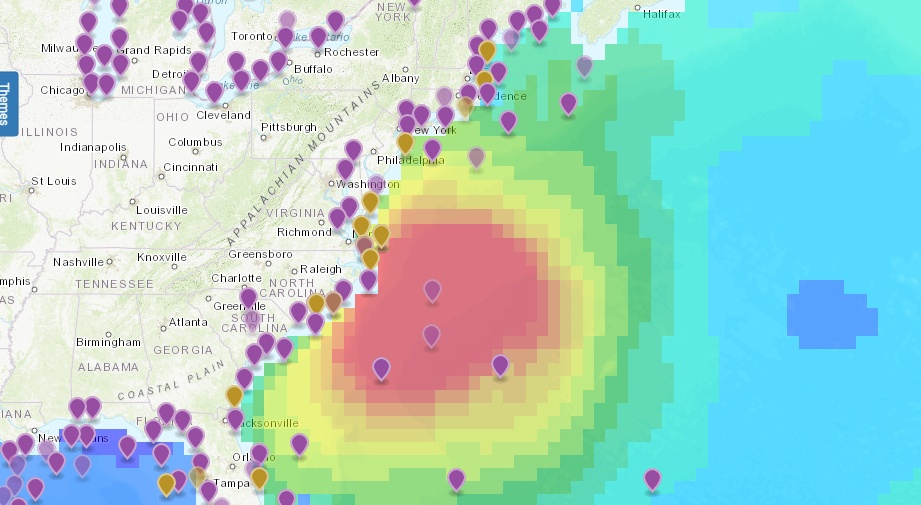

While it’s unlikely you’ll see a glider from the beach, you can follow glider missions online, according to MARACOOS Communications Director Mary Ford.

“Current glider missions can be seen at oceansmap.maracoos.org,” said Ford. “On the left menu select the glider data. You can also toggle through the time selection to see historical data.”

The interactive glider map may be a bit complex for the average person, but Ford says it will become simpler to navigate. “We’re currently working on making the website a bit more user friendly to the regular public.”