Put this in a category of limited ambition that you might call the Philadelphia Settle.

On Tuesday, Philadelphia primary voters will face a ballot question asking whether the city should set in motion a plan to increase its local minimum wage to $15 by 2025. Currently at $7.25, the floor set by the federal government, Pennsylvania is behind every single state you’d visit for a day trip, save for Virginia, which is the same.

When confronted with what raising the minimum wage could do for Philadelphia’s rotten reputation for being a poor big city, the city’s Commerce Director Harold Epps sounds exasperated.

“We don’t have to lead but we at least have to follow,” he said, sporting his native North Carolina drawl.

Plenty is working in Philadelphia’s economy.

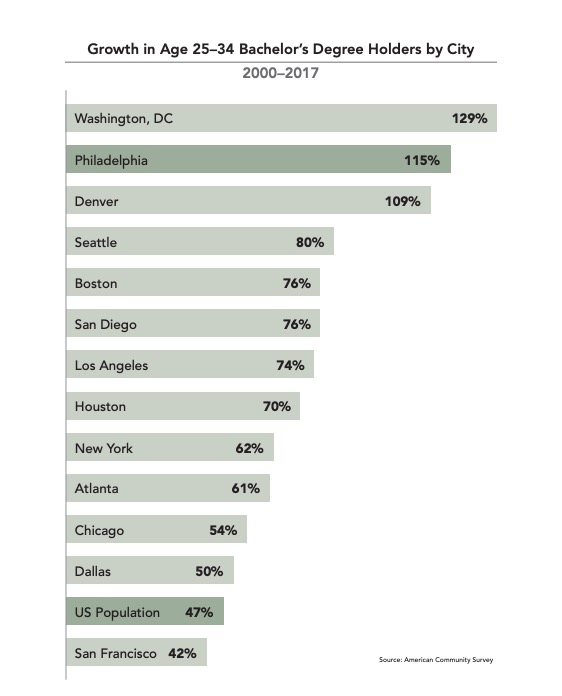

Deborah Diamond is the executive director of Campus Philly, the well-liked economic development nonprofit founded to pay attention to the attraction and retention of college graduates. She has the good fortune to show up and share cheery statistics of what many of us take for granted: In the last 20 years, Philadelphia has become a national success story in retaining college graduates. (Reminder, Philadelphia’s college brain drain stereotype was pronounced dead in 2010.)

Between 2000 and 2017, Philadelphia city gained a remarkable 68,000 residents with college degrees. (Contrast that with the net 3,400 this city lost between 1990 and 2000, Diamond said.)

Still — or maybe, in part, because of it — of big U.S. cities, Philadelphia has the third-highest rate of income inequality, behind only Atlanta and Miami. In recent years, Philadelphia has gotten considerably more unequal, not because a change to its stubborn rates of generational poverty but because pockets of wealth have emerged. (Nonetheless, Philadelphia is notably both poor and “not wealthy.”)

For a class of progressive policy wonks, the most straight forward approach to this ugly label is an increase to the city’s minimum wage. Introduced by City Councilwoman Cherelle Parker, the ballot question is the first step in Philadelphia’s effort to break loose of state policy and follow a national conversation (and changing labor research).

“Poverty is a waste. How can you waste 26% of your people?” asked Richard Florida, perhaps his generation’s best known urbanist.

He was referring to the tortured statistic that more than one in four of Philadelphia residents live below the federal poverty line, a mark that has remained stuck for the last five years, as reported by last month’s annual Pew Research “State of the City.”

Florida was in conversation Thursday at Drexel with the university’s president John Fry. It was part of the year-long inaugural Philadelphia Fellowship Florida is in the midst of, culminating with a report this fall. In the audience was Bruce Katz, a noted public policy intellectual and a Drexel Lindy Institute fellow, and afterward a panel was moderated by the affable Alan Greenberger, a former commerce director under Mayor Michael Nutter as well as a Lindy fellow.

Though no one directly dove into the local policy and politics Thursday, there was no doubt a subtext.

The Pennsylvania Chamber of Business and Industry has been among the most consistent critics of the minimum wage boost effort here. Last fall, the Chamber of Commerce of Greater Philadelphia supported an attempt by Pennsylvania Republicans to squash local attempts to, among other things, grow the minimum wage. But the local Chamber has turned more muted on Tuesday’s specific ballot initiative. Notably Claire Greenwood, the sharp leader of the local Chamber’s CEO Council for Growth, did not voice opposition during the panel conversation that featured multiple calls for minimum wage growth locally.

Amid complicated national politics, Corporate America has been at times a champion of progressive issues — some have begun supporting the push to a $15 minimum wage, which has become a national rallying cry (and favored policy to critique).

In Philadelphia, the unambitious point is that Pennsylvania has fallen so far behind the rest of the region that Tuesday’s vote is no adventurous plight.

In February, New Jersey legislators finalized its five-year plan to raise the minimum wage to $15, following Massachusetts, New York state and Washington D.C. Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont seems likely to sign a bill into law that will raise that state’s minimum wage to $15 by 2023. Of nearby U.S. states, only Virginia has a minimum wage stuck at the $7.25 federal minimum, like Pennsylvania.

Already with the region’s lowest minimum wage and yet remaining a slow-growth state, speakers Thursday couldn’t quite name what economic strength is at risk for Pennsylvania residents. Though he didn’t say so directly, Florida himself seemed to note that Philadelphia’s employment mix in particular made it unlikely to be particularly challenged by a minimum wage increase.

Of the nearly 700,000 jobs in the city, 250,000 of them are in what he defines as the “creative sector” — knowledge and office workers, highly skilled and others associated with college degrees, Florida said. About 117,000 of them are in the so-called “working class,” which includes lingering industrial and manufacturing roles, the building trades and other craft roles.

The remaining 300,000 or so are in the service sector — restaurant, bar and cafe workers, many hospitality and tourism, some in direct-care and your Lyft driver. They earn just $27,000 annually on average and are disproportionately responsible for Philadelphia’s poverty rate.

“Pay service workers more, and you’ll have a more productive cycle,” said Florida.

Research from Florida’s consulting firm, the Creative Class Group, points confidently to it.

“Philadelphia’s income inequality is closer to Colombia” in South America than many U.S. cities, said Steven Pedigo, the firm’s director of cities and research; that comparison comes from the two geographies’ similar Gini coefficients, which measure the distribution of household income among individuals.

In a city with a swelling creative class, but slow to moderate growth and a declining middle class and services sector, Pedigo says research sees no negative net effective on local employment in any statistical scale.

Epps, the commerce director, signaling himself as a clear champion, said increasing the minimum wage would reduce poverty by accelerating wages faster than housing costs.

“This is not going to have an adverse impact on the [local] economy,” he added.

At Thursday’s event, inside from a beautiful spring afternoon, there was one particularly telling exchange. Standing at a podium, Greenberger mentioned to Epps, his successor as commerce director, that his team supported the local expansion of a commercial laundry firm named Atlantic City Linen that pledged to hire citizens with criminal records.

“I’ll tell you exactly what happened,” said Epps: They were $10-an-hour jobs and it was 120 degrees in the Southwest Philadelphia facility on many summer days. Many of those hired quit after their first paycheck, said Epps, “once they found they could make more money on the corner.”