Wilmington startup Desikant Technologies had pretty much flown under the radar in the Delaware startup scene before the Startup 302 competition. That’s where founder Kwaku Temeng’s pitch for the company’s thermoregulation “smart garments” earned him the top $75,000 prize in the Delaware Innovation Award Category, funded by the Delaware Division of Small Business.

Temeng, a longtime DuPont engineer, began working in the field of innovative apparel in 2013, when he moved on from DuPont and became director of innovation for Under Armour. DuPont first brought him to Delaware; he’d also earned his Ph.D. in chemical engineering from Georgia Tech, as well as an MBA from The Wharton School.

At Under Armour, he learned how heat stress gets in the way of performance, both athletic and in people’s jobs.

“Your body is working hard, it’s sweating to cool itself, but the sweat won’t evaporate enough to cool you off,” Temeng told Technical.ly. “[Under Armour] is where I became educated about the phenomenon and the impact.”

In 2017, he moved on again to an early-stage startup in New York City called Dropel Fabrics, which aimed to make performance fabrics from all-natural materials. He commuted from Wilmington for his position of chief innovation officer.

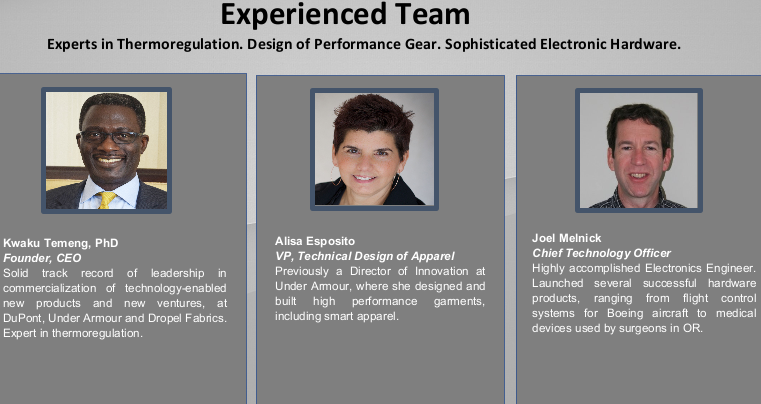

Then, in mid-2020, at the height of the pandemic, Temeng decided to start a startup of his own. He connected with a former Under Armour colleague, Alisa Esposito, who had built high-performance garments for Olympic athletes and electronic-integrated apparel, and brought her in as VP of technical design. Joel Melnick, an electrical engineer who had previously built flight control systems for Boeing and started his own company designing sophisticated devices for surgeons, was brought in as CTO, completing the core team.

Temeng, the visionary behind the company, drew inspiration from the autonomous vehicle sector.

“One day I had been thinking about the problem of how the sweat doesn’t evaporate, and how people are using all kinds of approaches that don’t work really well,” he said. “I was looking at each development and thought, you know, cars can drive themselves now, literally. You get in and the car is equipped with sensors and some intelligence, it can navigate around. So I asked myself, why can’t we do the equivalent for garments where we embed some sensors to monitor humidity and temperature?”

It took a couple of years to design a proprietary technology that fit with the vision of autonomous smart apparel.

The key, at its most basic, is to dehumidify the inside of the garment.

“Imagine wearing a jacket,” Temeng said. “If it’s fully zipped up and you’re active in the sun, before you know it, the inside of the jacket is really humid because the air inside is stagnant. We’ve built this little device with the dimensions of a smartphone that you connect with the jacket. The device is able to pull air from the inside and dump it out. Then what happens is, the ambient air around you will naturally flow in to fill the space. We’re pulling out the warm humid air to maintain a lower humidity on the inside of the jacket so your body’s natural sweat mechanism can work. You don’t feel anything, you don’t hear anything. You put it in and you don’t even have to think about it.”

Desikant got off the ground with Temeng’s own funds.

“I had to do that to get us to the point where we had something to show,” he said. “Luckily we were connected with the Army labs in Natick, Massachusetts, and they bought a couple of prototype units. Being able to fund that was important.”

The smart garments can be worn in lots of different situations, with surgeons, who often perform long, grueling surgeries that leave them drenched in sweat, being a major target market.

Everything the Desikant team has done so far, they’ve done virtually. Now, with the Startup 302 funds — the first major funding they’ve received so far — they plan to lease a space, as COVID-19 restrictions have been reduced.

The plan is to remain in Delaware.

“When the opportunity came to start this company, I thought, I’m already here, so why not [start it here],” Temeng said. “There are certain things that Delaware doesn’t have at this point in time. Delaware is loaded with companies in the chemicals and materials spaces. The thing we’re trying to do, there’s no strong presences, but my goal is to try and change that.”