The City of Baltimore was a pioneer of civic tech, data and the cross section of the two. As a trailblazer, the city’s government has had a front-row seat as views on how local governments use data morph from luxury to supplementary to necessity over 20 years.

For the city government, a big focus on using data started under the tenure of Mayor Martin O’ Malley 20 years ago with CitiStat. It was also around that time when the nonprofit Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance (BNIA), now housed at the University of Baltimore’s Jacob France Institute, was founded and began releasing civic data publicly with a focus on the community level.

In the years since, the city government went from gotcha stat sessions and charging for access to data to open data portals and CleanStat dashboards. It also became clear that leadership and culture among city agencies had to evolve alongside these tools, according to leaders who have seen Baltimore’s data-based governance initiatives progress through multiple administrations. Throughout, it was clear that the executive power of the mayor shaped the use of public data. With the city approaching a mayoral transition in December, the lessons from recent history offer a reminder that the day a mayor goes into office is the day it’s decided whether the initiative is relevant or not.

An early innovator in civic data

The concept of using data to govern across agencies was still new in the year 2000. When he took office, former mayor Martin O’Malley hit on the concept of collecting and analyzing data to have an informed and strategic approach to reducing the crime rate used by the New York Police Department, and applied it across all agencies of Baltimore’s city government. CitiStat was born.

Under this initiative, data was used to track progress of city agencies toward particular goals. On a regular basis — every month or every other week —agencies were brought to task on whether the benchmarks were achieved or not. It introduced a new measure of accountability for everything from potholes filled to streetlights fixed.

With all of this new data gathered internally, the city didn’t exactly know how to share it publicly. This early 2000s craze for data-based performance management precedes the revolution for open data of recent years. Data was valuable info for making policy and tracking community trends. But just as with some paper-based public records, government charged a fee to others for its use.

“Prior to the ‘open data’ concept, cities like Baltimore treated the data as a service that they would provide to companies or researchers and charge a service fee,” said Seema Iyer, who leads BNIA as the associate director of the Jacob France Institute, and is former chief of research in the Baltimore City Department of Planning. Baltimore wasn’t unique in this. Local governments saw data collection as a resource. CitiStat was an internal use of the data, so external sources needed to pay a premium.

CitiStat and Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance were created simultaneously — one to use data for the government, the other to use and share that data to the public. At this point, it was not quite open data in practice at the government level, but rather in spirit. With BNIA, there was an organization in the city researching and disseminating data with the citizens’ interest at heart.

Moving beyond the ‘gotcha’ moment

As Baltimore was growing the CitiStat model, Stat was taking off around the country. Governments from San Francisco to Somerville, Massachusetts began to adopt data-driven initiatives. Baltimore was a model from which to learn, even as these other municipalities applied their own approaches. After he was elected governor of Maryland in 2007, O’Malley brought the stat concept to the state level. This growth was based on a reputation that the approach was effective when it came to creating efficiency and savings. A 2007 report from the Center for American Progress noted that Baltimore saved $350 million during O’Malley’s tenure due to the program.

Yet inside city government, mixing data and a human workforce had its hurdles. In a 2008 report on these initiatives, Robert Behn, a lecturer in Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, noted that Baltimore’s Citistat meetings were described as “brutal, unsentimental affairs.” In these early years, gotcha stat was all the rage.

“You went before the mayor and you probably didn’t know what the mayor was going to ask you, or what issues were going to be presented during that meeting,” said Tiffany Davis, a senior advisor at John Hopkins University’s Centers for Civic Impact, which works with cities across the nation to improve governance using data. “The department heads were in that ‘gotcha’ phase, thinking on their feet, trying to figure out answers and solutions to satisfy questions.”

It led to a lesson: Applying accountability measures to achieve results isn’t just about numbers.

“It makes them afraid,” Davis said of this approach. “At the end of the day we’re all adults, and if you’re an executive leader or department head, you should be able to answer questions when they are presented to you. But it’s not always about what you’re doing that can put a bad taste in a person’s mouth, it’s important how you do it.”

There was also a question of making the data available. Babila Lima has worked for the city of Baltimore since the administration of former mayor Sheila Dixon, and is now the director of the Baltimore Department of General Services’ Business Process Improvement Office. In his experience, mayoral administrations have been pretty open to collecting and utilizing data. It’s when you go down the chain of command that you start to run into issues with sharing data for review.

With a focus on modernizing government processes, gathering and analyzing performance data is a big part of Lima’s job, but there’s also a human side to enacting change. Lima said one difficult part is overcoming the stigma of a bygone era where data was used to turn up the heat on a government official, and make them squirm.

“I think generally people who have been with the city a long time or have less comfort with where we’re trying to go may initially have a perspective of, ‘I don’t want to expose my operational data or expose myself to these partnerships because of the gotcha moment,’” said Lima.

Lima said when it comes to data, he eases fears of colleagues being called out for incompetence or negligence. After all, if the data you offered is being aimed back at you, it can be hard to feel like anyone is on the same side.

But over the years, there has been an effort to encourage sharing data as a part of collaboration among departments and outside organizations.

“There’s always a growing and evolving level of comfort with sharing operational data by agency. We try to meet them where they are,” said Lima. He aims to “let them know that there’s a lot of partners that are really committed to the city and aren’t looking for the gotcha moment.”

The evolution of the program through future administrations showed the importance of leadership to these programs. Iyer points to the hiring of a younger city chief information officer, Rico J. Singleton, in 2010 during the tenure of former mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake as a shifting point in attitudes on open data and data collection in the city. During this era, in 2011, city government launched an open data portal, Open Baltimore, where public data would be freely available. In this area, too, Baltimore was among the first cities to adopt a data-based approach.

To be sure, reports from these years indicate the effectiveness of these programs suffered amid turnover in leadership, as there were at least three different CIOs and multiple CitiStat directors during the Rawlings-Blake administration from 2010 to 2016. The turnover continued when former Catherine Pugh took office in 2017.

Yet, beneath the top leadership at the agency level in city government, there was a culture shift at play. The CitiStat program was heavily promoted by those two mayors, and attitudes in favor of open data and data-based governance improved, Iyer said. The CIOs got younger, and the management styles changed. Lima is an example of that new guard of department head.

The change brought a management style that is more solutions-oriented. Instead of using stats as a punitive sledgehammer, it’s a guide for better decision making.

“People are scarred,” said Lima. “There are different ways you can approach accountability. There was a gotcha culture. What we’ve been trying to do is work with people who share our values.”

Lima said they’re seeking “[Partners] that aren’t looking to expose failures, but see those challenges as an opportunity to say, ‘Maybe you don’t have the skillset in your organization to make immediate changes and if you don’t, how can we support?'”

‘Demand and opportunity’

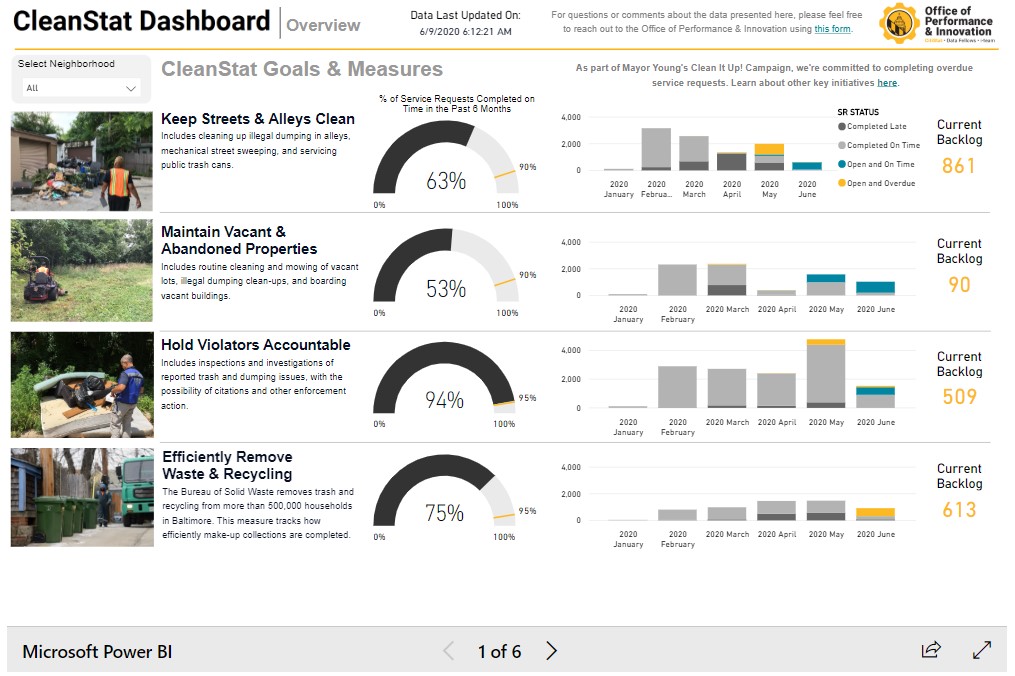

More recently, there’s fresh energy around using data in city government as a new home was created for the city’s internal innovation initiatives under Mayor Bernard C. “Jack” Young. In May 2019, around the time that Young stepped in to the top role after Pugh resigned amid scandal, the city created the Mayor’s Office of Performance and Innovation (OPI). Formed through a merger between CitiStat and the city’s innovation team, which was created in 2017, this created a hub for work on new approaches to tracking, improving and bringing approaches developed in the private sector to priority service areas. With this move, the city also added a data fellowship program, which puts data specialists in local government departments to find inefficiencies and create solutions in collaboration with the agency.

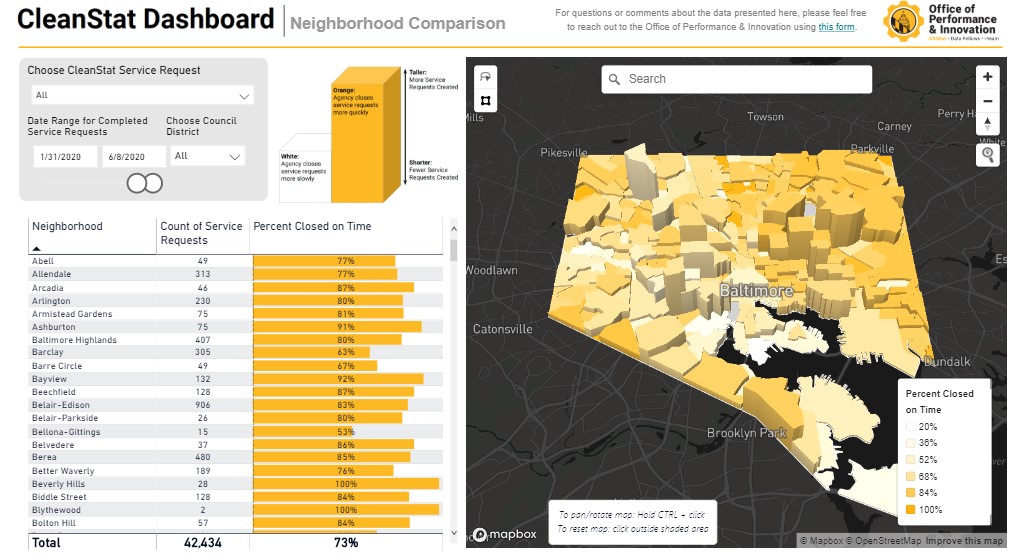

These changes brought new performance-focused initiatives, and tools for agencies. A tool launched earlier in 2020 called CleanStat, for instance, reshaped how the Baltimore Department of Public Works collected trash. The department was credited with turning a backlog of 16,000 orders into a few hundred prior to the pandemic.

OPI Director Dan Hymowitz, who started with the city as director of the innovation team in 2017, noted that the city’s long history with data management and CitiStat gives a lot of agencies a comfort with the process of using data in a systematic way to analyze performance. The culture around data is different, as agencies want data analysis because they see the value in improving performance, he said.

“If anything it’s been striking how folks want to use data more,” said Hymowitz, adding that more than 27 agencies wanted a data fellow. “It was a huge number of applications. There is a huge amount of demand and opportunity,” he said.

These days, individual government agencies take more ownership in the process of data management, and it’s not just coming from the mayor’s office.

Still, that doesn’t change how important the mayor’s office is to the health of CitiStat, or stat-based performance management in the city.

As Iyer put it, Rawings-Blake did a lot to promote the program, but the constant turnover decimated CitiStat’s effectiveness. Young, on the other hand, built a solid team around the program, letting the actions of the department speak louder than the press release.

Now, Young’s tenure is set to end in November, so there’s likely to be another turning point. In response to Technical.ly’s mayoral questionnaire sent to campaigns this year, all three general election candidates —Democrat Brandon Scott, Republican Shannon Wright and Independent Bob Wallace —said they were supportive of “developing plans and strategies for programs that apply data and regular accountability to the delivery of city services and policies, such as CitiStat.”

“Whether CitiStat is relevant is completely dependent on the mayor,” said Iyer. “It doesn’t tend to be why people elect a mayor — are you going to be a data driven mayor? That never comes up. Although, in some ways, it should. Everything that people care about, there is a strategic way to get there. And that’s what data should be used for.”