On the morning of her son’s 29th birthday party, LyVette Byrd woke up, and for the first time, she couldn’t see.

LyVette Byrd: At first I didn’t know it. I just thought I was a little groggy. So I just went into the bathroom.

She washed her face and was surprised that her eyes hadn’t opened yet. LyVette eventually raised her hand to open her eyelids herself.

LyVette Byrd: And then when I realized my eyes were open, but I saw nothing, then I realized “LyVette, girl, you blind.” That’s exactly what I said.

It was 2017 and LyVette was 48 years old. She didn’t want to call the hospital or doctor’s office. She wanted her son, Jonathan, to enjoy his birthday party. So, when her son’s godparents arrived that morning, Lyvette pulled them aside. She told them to stick by her side and describe everything to her.

LyVette Byrd: Nobody knew I was blind.

After the party, LyVette went to see her eye doctor. She’d had 20/20 vision, but doctors kept careful watch because she has type 2 diabetes. At this appointment, her doctor found that all of the blood vessels in Lyvette’s eyes had ruptured. That’s why she couldn’t see. The doctors gave her two potential scenarios. There was a small possibility that some of her vision would return, if they could go in surgically. The other possibility was that her vision would slowly, but surely fade away.

Nichole Currie: And were you working at the time?

LyVette Byrd: I was

Nichole Currie: Tell me about that.

LyVette Byrd: I was a liaison between community college and a program here in Philly called YouthBuild.

Her work consisted of helping students access resources at the Community College of Philadelphia. She was passionate about it — Lyvette had needed that kind of help when she went to college in her 40s. A lot of her work required a computer. After she lost her vision …

LyVette Byrd: What would take me minutes, took days because my vision was not getting better to the point that I can see to navigate the computer.

LyVette tried to complete most of her work on paper, and she often kept quiet about her vision. She was hoping it would magically return. After a little over a year and two surgeries, LyVettes’s vision did partially return to her right eye. But she could only see shadows and large figures. And doctors warned her that the return wouldn’t be permanent. Meanwhile, the sight in her left eye was completely gone. She was diagnosed as legally blind in 2019, when she was 50. It’s been a life-changing adjustment.

LyVette Byrd: So if I was born blind and my community is blind, everything is inside this blind world. And so everything I learned is inside of that. But for a suddenly blind person, they’re sitting on the side of the curb somewhere rocking, trying to figure out the rest of their life before they even get to that point.

Lyvette immediately applied for services through the Pennsylvania Bureau of Blindness and Visual Services, or BBVS. It helps visually impaired people in Pennsylvania get the resources they need to work — things like job placements, and assistive technologies like a special software that helps people use computer screens despite not being able to see them. But she was waitlisted.

LyVette Byrd: And then that was another trauma. And so when I realized I just could not do it anymore, then I had to have a sit down with one of my managers.

Without special accommodations, or the right tech, Lyvette didn’t think she could keep doing her job.

LyVette Byrd: What he wanted to do is to give it 30 days. I didn’t think I needed 30 days. I was kind of clear at that point when I, I can’t do this. He said, “Give it 30 days, see how it looks, ’cause you might be able to figure it out.” And we gave it 30 days and I couldn’t figure it out, so I had to leave it. So for a while I just sat like, “Hmm, what am I gonna do now?”

###

I’m Nichole Currie, and this is Thriving — an audio documentary about our economic future together. I’ve been following 10 Philadelphians for a year to learn what it takes to make it in America. After a pandemic and so much social upheaval: What are the obstacles and opportunities we all face to economically thrive in the United States? Each person we’re following tells us something different about our collective future.

In this episode, disabled residents.

We’re following LyVette Byrd, a 53-year-old in Philadelphia’s West Oak Lane who was diagnosed as legally blind and lost her ability to work.

Suddenly, she found herself encountering the barriers that many disabled people face in the workforce: low pay, a lack of quality jobs or the accommodations to do them, long waits for limited government assistance, and rising medical costs that can leave some living check to check.

“If I was born blind and my community is blind, everything is inside this blind world. And so everything I learned is inside of that. But for a suddenly blind person, they’re sitting on the side of the curb somewhere rocking, trying to figure out the rest of their life before they even get to that point.”

LyVette Byrd

LyVette Byrd: My family knows me as the caretaker.

For most of her adult life, LyVette has been the person her family depends on.

LyVette Byrd: I am a mother of many. I gave birth to four, but I’ve inherited a lot.

LyVette takes care of her oldest son, Jonathan, who is severely autistic. You can hear him in the background while we talk.

LyVette Byrd: And then I take care of my parents and two of my uncles.

So when LyVette was diagnosed as legally blind in 2019, it was unsettling for the roles to reverse.

LyVette Byrd: Because it’s not easy. It’s not easy. Being the person that I am in my family. When I lost my sight, my family did not know how to cope with that because I am still the go-to person. So it was like, OK, let’s hurry up and get you past this because you got to help the rest of the house. Like you have to help the rest of this family. Like we can’t picture you sick, we can’t have you this way. And in a sense, um, I had to get it together to do it.

LyVette was already living with her parents, and they chipped in a lot. There were the big things, like her father driving LyVette to her doctor appointments, which sometimes involve long and invasive procedures. The treatments can leave her without even her limited vision.

LyVette Byrd: A lot of times my dad is there, and I have to go back in the waiting room, like, “OK, Dad, it’s one of them times where I won’t be able to see you when I come out.” And they’re like, “OK, Boop, I got you.” And then I’ll come out, and … he’ll get me to the car somehow and he’ll get me in the house somehow.

Sometimes it was the small things, like her mother reading her favorite magazine to her.

LyVette Byrd: She’ll say, “Hey LyVette, you want me to read you The Daily Bread? This is what it says today.” And, At first it was like, “Nah, I’m good.” But she really wanted to do something for me. Something she knew I liked doing.

###

LyVette eventually sought financial support from the state. She applied for Medicaid from the Department of Public Welfare, and cash assistance, and SNAP benefits from the Social Security Administration.

LyVette Byrd: I didn’t wanna do that because if I did that, then somewhere in my mentals I was admitting that I’m not gonna get my sight back ever. And I was still in denial.

Nichole Currie: So what pushed you to do it?

LyVette Byrd: Money. Money. I was living with my parents, wonderful parents I have, but they were seniors and because they’re good in money, you know, we never lacked for anything. But I wanted to contribute to the household and I couldn’t do that without that money. I needed to be able to pay them some rent from where I was living. I needed to have just more than just nothing.

LyVette Byrd: Because the other thing that I was thinking at the time, um, is that if I stay where I am, then I’m not gonna progress. This is where depression will set in. And I saw myself heading that way.

When I meet LyVette in the summer of 2022 — three years after she was diagnosed as legally blind — it’s clear that she’s benefitted from some public resources. She moved out of her parents home and into an apartment under the Philadelphia Housing Authority Housing Choice Voucher program, in which the PHA subsidizes a portion of rent payments. LyVette was also issued food stamps and $1,193 a month in cash assistance from the Social Security Administration. Realistically, all of this is just enough to keep LyVette sheltered and alive.

LyVette Byrd: $1,200 or less is what most people get and they have to navigate life outside of that. Even with that, we’re still below the poverty line. So what keeps us from — and I say us as a collective — as a grouping of people that are disabled, how can we get above the poverty line?

As of 2023, the poverty line in Philadelphia is just $14,500 for a one-person household. That $1,200 a month from the state barely gets LyVette there. But she’s grateful, and she’s found ways to make the best of her situation.

LyVette Byrd: Thrift stores are my favorite things. Oh my God, I like thrift shopping.

And she finds different ways to stretch her money.

LyVette Byrd: OK, well this month I’ll put $25 away. Won’t touch that $25. Next month I’ll do it again. And then $50, I can buy a pair of shoes. But it’s hard. It’s really, really hard. But I can’t see how yet I can go out and work a 9 to 5 or 10 to 6, or however it is, right? Um, gain that money to do what I need to do.

###

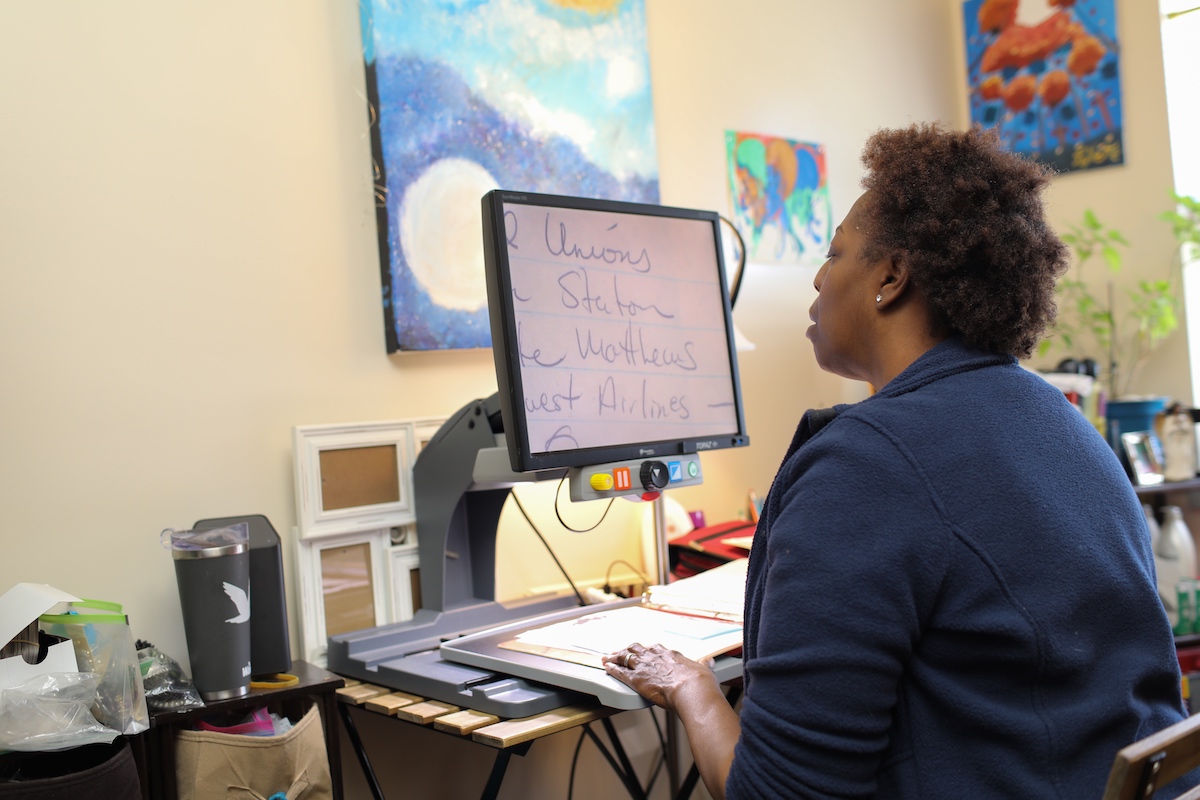

Lyvette would love to go back to work, and back to doing something she’s really passionate about. But doing so has become incredibly complicated. Lyvette is still waiting for help from the Bureau of Blindness and Visual Services — including access to software that would allow her to work on a computer. There’s a program called Job Access with Speech, or JAWS, that will read the computer screen for LyVette. It will tell her what to type or if she’s made a mistake in her typing. She’d need to take a three-week class to learn how to use it — and BBVS can make that happen by paying for the software and offering the class free of charge. But it’s been three years now since she first applied.

LyVette Byrd: One year, I had an interview. They did my application. I was accepted, but the money wasn’t there.

Nichole Currie: The money for the program?

LyVette Byrd: The money for the program. So then they waitlist you. You are on a wait list. Then when money goes into the pool, they send you a letter and say, OK, you’re off the waiting list. What do you need again? And then they gotta go through, oh yeah, this still applies. This doesn’t apply. Da da da da da, da da. And then there’s supposed to be counselors that’s reaching out to you to say, OK, now let’s set you up for these classes and trainings so that you can get all the stuff that you need.

But LyVette hasn’t received a call yet. All of this has prompted her to get into advocacy work. She joined the National Federation of the Blind of Pennsylvania. It’s an organization that advocates for the rights of visually disabled people. She’s met lots of people who are waiting for the same resources she is from BBVS. People who are at a loss for how to stay financially secure without the resources they need to work.

Nichole Currie: So what now …

LyVette Byrd: You know what I found? A lot of us, we create our own organization and business opportunities and we market ourselves just that way.

She’s found many disabled people get around these barriers by finding ways to employ themselves — like being an independent contractor or opening a business. It can help people avoid the scrutiny and skepticism that they might face with a traditional employer.

LyVette Byrd: It’s easier. When I market myself and you even read on paper all that I do, right? And I do it as an independent contractor offering my services. They say, “Oh, you can do what?” And then they just hired you to do it. They don’t ask you how you doing it. So in the meantime, what do I do? I start breathing life into this business that I’ve had so that I can manage.

Lyvette had registered a business in 2003 — For the Byrds Consulting — but she left it on the backburner. After she lost her vision, she revived it. She wants to use the business to help people organize and plan community events, and to help entrepreneurs set goals.

LyVette Byrd: And that’s easier for me in a sense because I’m in control of that. But here’s the thing. I still need those resources.

Like that computer screen reader from BBVS. It would help LyVette, for example, type her own meeting notes versus needing a sighted person to type them for her.

LyVette Byrd: Because I was already told to me that my eyesight’s not going to get any better. It’s going to get worse. And I’m still going to need those tools to run my own business, if I’m going to keep it.

LyVette has a team of two volunteers helping her — her daughter and a close friend who is also legally blind. So far, the company isn’t bringing in much money. Lyvette thinks if she keeps working at it, in three years, it could be profitable. It feels like that’s one of the only options she has right now, especially without the assistance she’s been waiting for.

“My eyesight’s not going to get any better. It’s going to get worse. And I’m still going to need those tools to run my own business, if I’m going to keep it.”

LyVette Byrd

Julie Zeglen: Philadelphia is a hard place to need services.

This is Julie Zeglen, Technical.ly’s managing editor.

Julie Zeglen: It’s an especially poor city. It has a lot of people to take care of. And there are a quarter-million disabled residents in Philadelphia. So there’s an access gap, there’s a services gap.

For many disabled people across the country, it’s hard to find a job that’s both accommodating and well paid. This especially rings true for people with visual impairments.

Julie Zeglen: Because a lot of jobs are set up for seeing people, for instance, if you’re blind. But good jobs are also needed to be able to afford some of the upgraded technology that they need.

And when disabled people seek out resources for work, they are often left on the backburner.

Julie Zeglen: So even though there are programs to support them, sometimes it can take a long time to get access to that funding or get access, access to the technology in the first place, and then they need to learn how to use it.

Waiting for access and funding can wreak havoc on their lives. People often have to live off of Social Security or welfare until resources are available.

Julie Zeglen: One person we spoke to mentioned that she lives off of $800 a month in Social Security income. She also works part-time as a massage therapist. She feels that she’s unable to earn enough money in her job that she can’t survive without this Social Security income. Both, however, aren’t enough even put together.

That’s where LyVette is — trying her best to put her new business and state resources together to push her a little closer to being self-sufficient again. But even put together, she’s barely scraping by.

###

In late October, I attend a For the Byrds Consulting event. It’s at a church in Germantown.

It’s a women’s empowerment conference, and in the end, LyVette says it was a success. The tickets for the conference were priced at about $80, and she sold out the night before. But the sales she made covered exactly what she had to pay speakers, caterers and entertainment. Basically, she broke even. Either way, she’s happy about the turnout and hopes her business will keep growing into a sustainable source of income.

LyVette Byrd: And it made me feel like it was worth everything that I went through, and I went through a lot. It was worth it. There was so many times that I was supposed to quit in my mind. // Like, that’s like, I cannot. Oh, I almost gave it up a lot of different times.

Nichole Currie: And when you say you went through a lot, that was about, you know, trying to quit?

LyVette Byrd: Yeah, but I wanted to quit because of other events that was happening.

###

LyVette Byrd: John David, look at mommy…

Even though LyVette’s happy her business is picking up, her life didn’t stop at home. There were a lot challenges happening in the background. First, her son Jonathan began to have issues with his hearing. That meant scheduling additional doctor appointments and finding someone to drive them. Fortunately, Jonathan’s hearing was restored, just in time for another roadblock. Medical bills.

LyVette Byrd: One of the things that’s ridiculous is this: my health insurance. If I have Medicare and insurance bill, why am I paying for stuff? Why am I paying for? Why I gotta pay almost $500 for a bill?

Nichole Currie: $500?

LyVette Byrd: $500. Maybe you can see. I know you can see better than I can. I think it’s $580-something.

Nichole Currie: Yeah, $582.

LyVette is showing me some of her recent medical bills. After almost four years of being on Medicaid through the Pennsylvania Department of Public Welfare, she is being forced to switch to Medicare through the Social Security Office. With Medicare, LyVette pays a copay for all doctor visits, procedures and prescription medicines. On Medicaid she didn’t pay ANYTHING. It’s an adjustment.

LyVette is unsure about why the switch happened, but her case manager says that sometimes DPW will make a case that you no longer need Medicaid based on the cash assistance you’re getting from the Social Security Office. For example, they may think $1,200 a month in cash is enough for LyVette to pay a copay for a doctor’s appointment or surgery. But new costs are affecting her ability to get what she needs — like new glasses for her right eye, the one she still has partial vision in.

LyVette Byrd: Because of my level of blindness, I need two separate pairs.

With Medicare, she has a $300 allowance for glasses, but only one pair is covered.

I said, “But that doesn’t make sense.” They said, “Would you like to file a grievance?” And I said, “I surely would.”

The grievance didn’t work. LyVette was forced to pay for the second pair herself. The reality of her medical bills has forced her to rethink her relationship with doctor visits.

LyVette Byrd: Now I understand my seniors that don’t go to the hospital, even when they’re sick, cause they don’t want that bill. They make a choice. So I have to make a choice. Annual visits are a must. Mammos, a physical, my eyes, a must. But outside of those things, it’s limiting my times going to the doctor’s.

But she has one medical issue that has to be taken care of now — a surgery on May 15 to remove a cyst on her right ovary that doctors are worried could become cancerous. She tells me the procedure is simple, not too invasive. She expects to stay in the hospital for only one night.

###

But on May 28, I get a text from LyVette. She’s still in the hospital. I quickly do the math. That’s 12 days more than she had planned.

She says to call her.

Nichole Currie: What’s going on?

LyVette Byrd: Um they’re still trying to figure it out. I was supposed to come in here for a one-day procedure that turned into whatever day it is. And it is a bit overwhelming, is challenging for me right now.

When LyVette’s doctors opened her up for the simple procedure, they noticed a few issues that were life-threatening. That led to an additional 10-hour long procedure that extended her hospital stay. But then, LyVette didn’t fully recover. She couldn’t keep most of her food down. And soon doctors discovered that she had an internal bleed — which led to a third surgery.

LyVette Byrd: And what I found out is that my insurance coverage with the Medicare um, covers up to 80% and the 20% I have to cover still.

After 28 days, LyVette went home. But a few days later, when she told doctors she didn’t feel well, they urged her to come back. There, they discovered that she had blood clots. That turned into another week in the hospital.

###

While LyVette was gone, her other three children took turns taking care of her son, Jonathan, who often asked for his mother when he couldn’t find her at home. So when LyVette was finally dismissed, she was excited to come home and see him. But there was something else waiting for her.

It was a letter from the Bureau of Blind and Visual Services.

Before LyVette had her surgery, she’d gone to a conference for the National Federation of the Blind. She ran into a woman who used to work for BBVS. Over small talk, LyVette told her about her situation. The woman said she’d help. It was a quick conversation. LyVette didn’t think much of it or that anything would come of it. But it did.

LyVette Byrd: Monday, people were calling me. They called me about this class. // I don’t know who she called, who she talked to. But by Monday, things started to move.

And now that LyVette was back from the hospital and recovering, it was time to respond to BBVS. They paid for her to take courses at the Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired in Chester, Pennsylvania. She signed up for a three-week course in September to learn how to use JAWS, the screen-reading program.

The class is hard. Lyvette has to operate a computer with just the keyboard. That means using arrow keys to move the pointer on the screen, and memorizing shortcuts like CTRL + 4 to complete a task. The JAWS software can notify her if she’s made a mistake by saying it, or it can tell her what to type for training purposes.

LyVette’s taking a test to measure whether or not she can type out a passage that is being spoken to her.

“Not everybody has that resilience. So after a few times of getting knocked down, they just stay down. They just stay down.”

LyVette Byrd

LyVette says she’s quite lucky to get to this point in her journey, but she can’t help to think about others in the suddenly blind community. People who are still waiting for help, who can barely live off government assistance, AND those who aren’t fortunate to run into the right people at the right time, like LyVette did.

LyVette Byrd: I do believe I fell through the cracks. But I don’t think I’m the only one. I’m not the only one and I think unfortunately what happens is we all fall through the cracks, right? And we try and we push and then we get tired of pushing and then we settle and we accept. ‘Cause the fight is out of us at this point. And I don’t think the system takes in consideration, especially for those that are suddenly blind, suddenly going through this whole process. So we’ve never been blind before. We don’t know of a blind system. You know what I mean? We don’t know how things are supposed to be.

LyVette says she has her family, friends, and faith to thank for her perseverance.

LyVette Byrd: But what makes me sad is not everybody has that resilience. So after a few times of getting knocked down, they just stay down. They just stay down.

She gives me an example.

LyVette Byrd: There’s a woman who was in a class with me, this very class. And she’s so overwhelmed by it all, and she’s still in the grieving part of her sight, that it’s hard. So while she still wants to be connected to me, and I just met her through the class, she bowed out of the class. She gave up.

Nichole Currie: Why?

LyVette Byrd: It’s too hard. It’s too hard learning how to live another life when you’ve lived the life you have. 40 and 50 years is too hard. That in itself is too hard. And then when you have a system that doesn’t support you, then I gotta fight that, too? I’m fighting myself. And then I gotta fight that, too?

Nichole Currie: Do you ever feel that way?

LyVette Byrd: Yeah, every now and then I get the, like, “Oh my God,” you know, I get the blast-its. And it, but it doesn’t stay long. It doesn’t stay long because God is amazing, but my circle, my support will remind me, this is who you are.

Nichole Currie: In your own words, when you say people remind you of who you are. Who is LyVette Byrd?

LyVette Byrd: From a very humble place, I know that I’m a leader. I know I’m a teacher. I am a world changer.

For Thriving, I’m Nichole Currie.

Thriving is brought to you by Technical.ly and Rowhome Productions with support from the William Penn Foundation, Pew Charitable Trusts and the Knight Foundation.

Learn more about Thriving at Technical.ly.

Thriving’s executive producer is Technical.ly CEO Christopher Wink.

The series is reported, produced, and hosted by me, Nichole Currie.

Our story editor is Jen Kinney. Managing producer is Alex Lewis. Mix and sound design by John Myers.

Special thanks to Technical.ly editors Sameer Rao and Julie Zeglen.

This episode features music from Blue Dot Sessions and Philippe Bronchtein.

Our theme music is by Flat Mary Road.

Thanks for listening.