A court hearing in an armed carjacking case ended up producing major revelations about how the Baltimore Police Department uses secret technology to track suspects’ cellphones — and in turn also intercept the cellphone data of people who just happen to be in the area.

According to reports from the Associated Press and the Baltimore Sun, Baltimore Police Detective Emmanuel Cabreja testified Wednesday about how often BPD uses the Stingray, and for the first time publicly revealed an agreement between law enforcement agencies that prevents police from talking about it publicly.

It's staggering that the FBI is telling law enforcement to lie, which is basically what's happening.

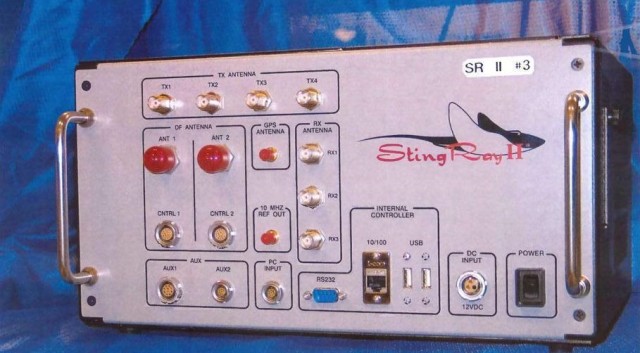

The Baltimore Sun’s Justin Fenton reports that, according to Cabreja, BPD has the latest Stingray model made by the Harris Corporation, known as the “Hailstorm.” Baltimore Police have used the device 4,300 times since 2007. Cabreja estimated he has used it 600-800 times in the last two years alone.

According to the AP’s Jack Gillum and Juliet Linderman, the FBI and BPD signed a nondisclosure agreement in 2011 which prevents any public disclosure about the Stingray — including in court and to other law enforcement agencies. Under the agreement, the FBI can even step in and ask for a dismissal of a case if agents suspect that word might get out about the Stingray in a court hearing.

Given the agreement, Cabreja’s testimony represented an about-face for BPD.

In November, prosecutors pulled evidence in a case out of fear that it would divulge information about the Stingray. This time, however, the detective detailed how police tracked a cellphone by tapping into Verizon’s network, entered the home where the phone was and used the Hailstorm to make the phone ring. The Sun’s report states the FBI briefed Cabreja prior to the hearing.

With his testimony, Cabreja revealed that using the Stingray is pretty common in Baltimore. Stingray use was also revealed by the New York Civil Liberties Union in Erie County this week, according to Wired. In that department, the device was used 46 times since 2010. Compare that with the 4,300 uses since 2007 in Baltimore.

And that doesn’t mean that cellphone data for 4,300 cellphones. The device acts like a cellphone tower, intercepting data from all of the cellphones in the radius of roughly a city block. To ACLU of Maryland Staff Attorney David Rocah, that means the number of people whose cellphone data was intercepted is “orders of magnitude larger than the number that we know.”

“Given how widely used cellphones are in a dense urban environment like Baltimore, the numbers are staggering,” said Rocah, whose organization is working to get the word about the use of the Stingray and the secrecy surrounding it. Additionally, details about what kind of cellphone data the Stingrays intercept still aren’t fully known.

Beyond the numbers, however, Rocah is even more troubled by the nondisclosure agreement. In the November case, the nondisclosure agreement may have sounded like a police officer’s excuse. But Cabreja proved that it exists.

The document states that it is necessary for the FBI to keep the Stingray a secret so that suspects can’t figure out ways to avoid tracking. In doing so, the agreement instructs Baltimore police and prosecutors to essentially ignore court orders to produce evidence of how evidence was obtained. That strikes Roach as a violation of the Fourth Amendment, since it prevents courts from proper legal analysis.

“It’s staggering that the FBI is telling law enforcement to lie, which is basically what’s happening,” he said.

Just like in the larger national privacy debate over the NSA’s domestic wiretapping, the methods used by police to obtain permission to use the devices are also at issue. Maryland law requires police to get a court order to use a device such as a Stingray, but Rocah argues that the orders BPD obtain are also essentially misleading.

It was previously disclosed that police secure a court order to use a pen register device. Those devices only track calls in and calls out, rather than data from a whole block of cellphones.

“A Stingray is not a pen register,” Rocah said. “By seeking to cloak the use of the device … that is intentionally misleading the court. That should be sanctionable conduct.”

For those keeping score at home, “sanctionable conduct” means “people ought to be going to jail for this.”