“We are at war in cyberspace,” said Barbara Mikulski, addressing a crowd gathered in downtown Baltimore last October.

The war cry from the compact Mikulski, all four feet, 11 inches of her, might serve more to stultify a line of troops than provoke them into charging across a grassy plain — or logging into their World of Warcraft accounts. But when the U.S. Senator from Maryland delivered her remarks at the second CyberMaryland Conference, the very words contained an unmistakable sense of urgency.

“We are at war and we can’t forget it,” she said. “The battlefield is real, and the battleships are being built right here in Maryland.”

While it’s an easy charge for a politician to make in 2013, Mikulski gave her cyber pep-talk about three months before hackers took control of the Twitter accounts of the New York Times and Evernote, among others, and a Virginia-based cybersecurity firm traced 115 cyber attacks perpetrated against U.S. targets back to the Chinese army.

Cyber attacks are here to stay, and jobs making products or providing services that protect against phishing, malware, network intrusion, unauthorized access to data, computer viruses and the decryption of computer security codes — especially in regard to business and government — will increase in response. Which means more money pouring into a growing industry.

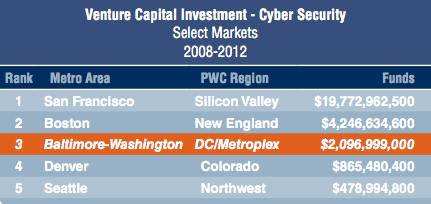

In other words, Mikulski and her comrades know what they’re doing when they call Maryland “Fort Cyber” and the “epicenter” of cybersecurity, which is projected to be a global industry worth $68 billion this year — it’s time for the state’s cybersecurity firms to exercise the benefits of proximity to Washington, D.C.

In 2012, cybersecurity contracts awarded by the federal government totaled $10 billion. By 2017, that number will be $14 billion. No wonder Mikulski and her Maryland colleagues in Congress have spent years shepherding hundreds of millions of dollars in federal money earmarked for cyber spending to home districts.

But what is the economic influence of Maryland’s cybersecurity industry on Baltimore? Do those dollars turn into jobs for city residents? No one would begrudge the Baltimore area’s technology community a regional distinction, especially after Columbia cyber firm Sourcefire was acquired for $2.7 billion last week. For Baltimore to profit, however, it must sell its virtues as a city-based cybersecurity sector — without stifling creativity in its startup scene.

If we narrowed the focus to just within a mile of downtown Baltimore, I’m certain the number of cybersecurity jobs would be way less.

Rick Geritz is probably the perfect pitchman for Maryland’s cybersecurity sector.

He’s part of the organizing board behind the National Cyber Security Hall of Fame, with offices on the campus of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). Geritz is also chair of CyberMaryland, an initiative launched by and funded mainly by the state in 2010 that operates today more like a listening committee, a way for private cybersecurity companies to tell state officials what would help them attract workers and contracts.

But Geritz will tell you that the cybersecurity industry begins in Baltimore, as he did at a press conference one day before a computers-for-guns buy-back in early July.

“Baltimore city is the hub of the world of cybsecurity,” he said, flanked by several high school students aspiring to careers as hackers for the U.S. government, and getting an early start with Ethical Hacker courses at downtown IT training nonprofit Digit All Systems, which hosted the buy-back event.

A quick inspection of the local cyber scene backs up Geritz’s assertion:

- Close to 20,000 open cybersecurity jobs are available in more than 1,800 cybersecurity companies in Maryland, according to the first local Cyber Security Jobs Report published in January, with slightly more than 13,000 of those open positions in the Baltimore region, including the city.

- The annual CyberMaryland Conference, in its third year this October, is held at the Baltimore Convention Center, which asks cybersecurity businesses to set up exhibits and do recruiting in the city for at least a couple days each year.

- The Cybersecurity Investment Incentive Tax Credit, approved by the Maryland General Assembly this year, hands refundable tax credits to startup cybersecurity firms that move to or are founded in Maryland, so long as they’ve secured $25,000 in investment from an investor or investment firm.

- And these developments, if cyber spending is an indication, appear to be good for Baltimore. Cybersecurity spending by private companies will hit $3.8 billion in 2016.

More than 13,000 cybersecurity jobs are in the Baltimore region. Graphic from the Cyber Security Jobs Report.

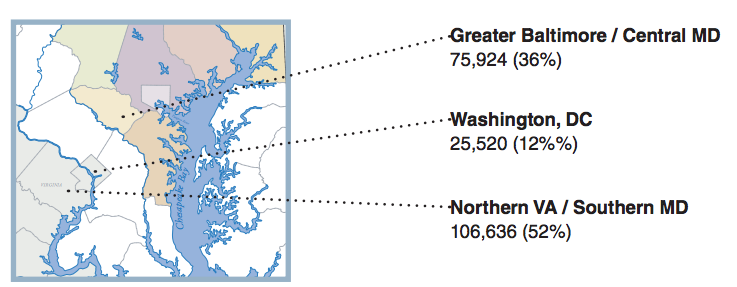

But digging a bit deeper into the data clearly shows just two major trends. The first is that cybersecurity activity is mostly concentrated in the counties south of Baltimore:

- Nearly 76,000 people in the “Central Maryland Region” and “Baltimore region” combined are already employed in cybersecurity jobs, according to a Cyber Security State of the Market Report released this month by the Economic Alliance of Greater Baltimore (EAGB). But counting only the employees in the amorphous “Baltimore region” leaves us with slightly more than 39,000 employees in cybersecurity in the city.

- The National Security Agency and U.S. Cyber Command are both housed in Anne Arundel County County at Fort Meade, the state’s largest employer with almost 60,000 employees.

- Local offices for Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Booz Allen Hamilton and Raytheon, as well as other defense contractors with the federal government, are located in Anne Arundel, Howard and Baltimore counties.

And the second trend? Inconsistencies and imprecision in the data available fail to illustrate a clear picture of how many cybersecurity workers are in Baltimore versus how many are outside of the city.

“If we narrowed the focus to just within a mile of downtown Baltimore, I’m certain the number of cybersecurity jobs would be way less,” said Peter Kilpe, a creative director at CyberPoint International, which put together the Cyber Security Jobs Report.

Click here to view a map of regional cybersecurity firms.

CyberPoint, with offices just off Pratt Street overlooking the Inner Harbor, is one of a handful of cybersecurity destinations in Baltimore. Founded in 2009, it handles both government-contract work and commercial work for private companies, and has grown from four to 130 full-time employees “precisely because of where we’re situated,” Kilpe said.

The battlefield is real, and the battleships are being built right here in Maryland.

But it’s hard to quantify the cybersecurity industry as a whole in the same way. “No job listing says cybersecurity expert,” said Patrick Dougherty, a market and research analyst at the EAGB, which pulled the numbers for its report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and had to dig deeper past job titles to analyze the industry.

Ironically enough, the cybersecurity jobs report that Kilpe and others at CyberPoint International helped assemble—in part designed to answer how many jobs in cybersecurity exist in the Baltimore area—demonstrates the central problem with quantifying the cybersecurity industry: it’s diffuse and oftentimes escapes definition, as systems engineers, cloud administrators and network analysts might be doing pure cybersecurity work as a “cyber security engineer,” or doing more traditional IT work that just happens to have a cyber component.

More than 208,000 cybersecurity employees are divided among Maryland, Northern Virginia and Washington, D.C. Graphic courtesy of EAGB.

“When you try to define cyber, it very quickly becomes other things,” said Patrick Tonui, a program manager for security and IT at the Maryland Department of Business and Economic Development. “Some of that is general IT. Some it goes to software development. It’s difficult to pull out cyber numbers.”

And because much of cybersecurity is “driven by classified work,” Tonui said, “the numbers aren’t released anywhere.”

There’s a legion of Edward Snowdens in Maryland toiling away at cybersecurity contractors like Booz Allen, but there’s no way to definitively count them all. That means it’s a fair bet that cybersecurity workers are “skipping over Baltimore,” as Kilpe put it, to find cybersecurity jobs at firms in other parts of the state.

“Are people moving to Columbia and Annapolis to take some of those jobs? I’m sure they are,” he said.

Kilpe’s observation belies a subtle truth: in talking about cybersecurity, programs and companies outside of Baltimore are often lumped in with the city’s tech ecosystem.

“The nexus of the cyber is sort of Annapolis, Baltimore, Baltimore County, Montgomery County, Prince George’s,” said Richard Forno, the director of UMBC’s graduate program in cybersecurity and an assistant director of UMBC’s Center for Cybersecurity, which launched in late 2012.

Now in its third year, UMBC’s cybersecurity grad program has at any one time about 150 students enrolled, Forno said. Most of those students are already working at places like Fort Meade, either at the National Security Agency or U.S. Cyber Command, or at private contractors like Raytheon and Northrop Grumman.

“Students come to us because it’s a hot field,” said Forno.

In addition to students, UMBC attracts its fair share of startup cybersecurity companies thanks to its Cyber Incubator at the university’s Research and Technology Park. More than 20 startups are affiliated with the Cyber Incubator, either by leasing space directly or through the Cync Program, a partnership with Northrop Grumman to help early-stage startups bring their cybersecurity technology to market.

Of course, people running startups at UMBC’s Cyber Incubator or working cybersecurity jobs at firms in the counties could be Baltimore residents.

But what’s potentially overlooked by the development of cybersecurity startups at a Baltimore County university, or promoting job opportunities at Fort Meade, or politicians cheerleading cybersecurity as a natural focus for Maryland’s collective tech efforts, is a focus on the general technology scene in Baltimore, whose desire to be more respected as a startup hub on a national level is particularly acute.

Here’s where the focus on developing a statewide cybersecurity industry collides with the needs of a city’s nascent startup ecosystem. To be appealing for startups, a city needs talented developers, venture capital and aggressive potential founders, not to mention staff that enjoy the culture within Baltimore’s limits.

Betting big on an industry driven by government defense — well, that’s one way to grow the state, but also an expedient way to stifle technological creativity in a local tech community that thinks it can hang with the likes of Boston and New York City.

Suppose, though, that Baltimore could become a terminus for cybersecurity firms. A cybersecurity-themed conference can’t be the one distinguishing marker if the city is to share in the bounty of Maryland’s overall cyber riches. Granted, large cybersecurity contracting companies are a bit constrained in where they can locate.

“The government has certain qualifications for distance,” said CyberPoint’s Peter Kilpe. “Some contracts you have to be within a certain radius.”

Smaller cybersecurity startups, though, could follow the path that CyberPoint has tread, with the right backing and support. For instance, the Maryland Technology Development Corporation routinely makes investments in Baltimore-based startups — its Propel Baltimore fund makes being in Baltimore a condition for funding — but how much of the $20 million in its forthcoming Orange Knocks Cyber Fund will go to city-based cybersecurity startups? How many more cybersecurity startups like Riskive, which is located in Federal Hill, can count on setting up in Baltimore and raising venture capital? (Not many, if the founder of Silicon Valley investment firm Allegis Capital, is right.)

Baltimore city is the hub of the world of cybersecurity.

Those are questions that, despite the piles of data, are more difficult to find answers to. Overall cybersecurity job numbers make it relatively easy to extrapolate the effect of cybersecurity on the state economy, but much harder to ascertain any potential benefit for Baltimore.

CyberPoint is at least one cybersecurity firm that sees advantages to being in Charm City.

“That’s one of the reasons we’re here—Baltimore’s a fantastic place to be,” Kilpe said. “We’re going to stay here longterm because we believe in the potential.”

Tonight: Join Technically Baltimore at CyberPoint International tonight for a presentation about Maryland’s rapidly expanding cybersecurity industry — and how the Baltimore region’s broad, general technology community can become better partners with the state’s cyber sector. RSVP for free.

Join the conversation!

Find news, events, jobs and people who share your interests on Technical.ly's open community Slack

This Black gaming advocate has a mission to transform education through esports

This Week in Jobs: Get out there with 22 new job opportunities available to you!

This national network empowers Black nonprofit leaders through community, capital and capacity