For Women Who Code DC Director Charlotte Lee Jackson, the fight for traffic safety in DC is practically in her own backyard.

At an intersection in her neighborhood of Friendship Heights, preschool staff have to cross a busy street with young children, all the while getting yelled at by aggressive drivers. Jackson made a complaint about this, but reps from the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) said they couldn’t add any traffic calming measures, since it was on an arterial road.

The experience made Jackson, who acknowledges she has the time and privilege that allowed her the chance to advocate for her neighborhood, wonder what was really getting done in communities lacking the same resources.

“I was like, ‘If you’re responding this way to me, I’m a Ward 3 white lady and I’m asking about this intersection on behalf of a bunch of small children and you guys are giving me the blow off, are you helping anybody in this city?'” said Jackson, who works as a data science lead.

She’s not alone in her concerns about DC cyclist and pedestrian safety. Just this week, a man was struck in a hit-and-run on 18th and Newton streets and is in critical condition. In April, a four-vehicle crash killed one bicyclist and injured three other people, and cycling advocate Jim Pagels was struck and killed mere hours after tweeting about the unsafe roads in DC. These events brought calls for more safety measures from advocates and community members around the District.

Jackson’s tech background couldn’t calm the traffic in her neighborhood, but she could apply it to make sure the data regarding traffic decisions was as accurate as possible. The experience led Jackson and fellow traffic safety advocate Michael Eichler to draw on their tech skills to help create safer streets for bikers and pedestrians. Six months ago, Jackson began the DC Crash Bot project through civic hacking org Code for DC to scrub and analyze car crash data, particularly accidents involving pedestrians or bicycles. The goal: to paint a more accurate picture of DC’s traffic conditions.

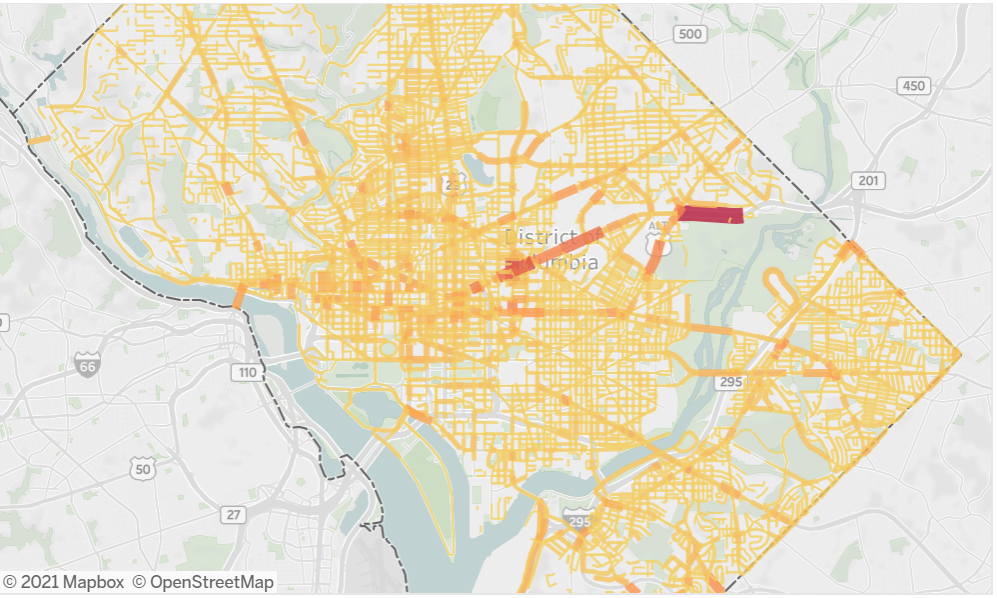

The project, which also has about a half-dozen regular Code for DC contributors working on it, began by joining together datasets involving traffic data into a relational database to see correlations between things like speed camera installations and car crashes.

Now, the group is working on updating the existing data. Jackson said that while the District’s Open Data DC portal does offer crash data, it only goes off of police crash reports, which typically only occur after incidents where someone was injured, a law was broken or property damage occurred. Given police distrust or fear of violence in low-income and communities of color, Jackson added that many might not want police on the scene at all. This means that a number of crashes, particularly those in wards east of the Anacostia River involving pedestrians, don’t end up getting reported.

“You miss a lot of these these crashes where somebody was injured, but the person just doesn’t want it engaged with the police for probably very understandable reasons,” Jackson said. “So we’re working to bring in those car crash calls from the 911 dispatch system and record those and map them and bring to light those crashes that…have an ambulance sent to them and they happen and maybe somebody got hurt, but they’re just never going to be in police reports.”

Dispatch data also doesn’t specify things like whether or not a pedestrian was involved in a crash or how many vehicles. Right now, the team is working on transcribing dispatch calls themselves using OpenMHz, which allows a user to listen to police and fire radio. Once that’s done, she’d like to begin including Twitter data where people post about non-reported incidents or close calls.

This work coincided with Eichler’s project developing a dashboard featuring some of the most dangerous roadblocks in the city. Jackson and Eichler, who is an advisory neighborhood commissioner and planning advisor at WMATA, are hoping to create a website that combines the updated data and the dashboard to create an accurate and easy-to-use resource people can use for advocacy. The current data can be accessed on Tableau with a password, but the pair would like to get it on Datasette so anyone can see and use it.

Eichler is also working on putting together a group for data visualization and analytics to create additional dashboards and find patterns in the crash data. Instead of just noting that a crash occurred, data that shows whether or not there have been other crashes on that same road can help note problem areas.

“It’s really hard to get anyone to pay attention when you say…’Traffic, bad. Road, dangerous,'” Eichler said. “But if you say there was 15 crashes on this block in the last two years, then you can say, ‘Oh, well, let’s look at that block and see what the problems are.’ So being specific with numbers and locations is really key to finding solutions to these problems.

If you don't have that data about where crashes are happening or if that data is incomplete, you'll be making policy and enforcement decisions based on biased data that doesn't reflect reality.

Jackson and Eichler hope that the completion of the project can help both with accurate policy and decisionmaking in regards to traffic safety, seeing as biased or skewed data can mean that communities most in need of traffic solutions can be missed. They’d also like the data to be accessible so people — like Jackson — can use it for personal advocacy in their neighborhoods.

“If you don’t have that data about where crashes are happening or if that data is incomplete, you’ll be making policy and enforcement decisions based on biased data that doesn’t reflect reality,” Jackson said.

In the end, the data and the stories of people work hand in hand. Eichler noted that since there’s only a finite number of resources for traffic solutions, such as policy efforts and funding, it’s crucial those are implemented in the places that matter most. Accurate data, he said, especially when it includes personal anecdotes such as the Twitter posts and personal stories from victims, is how you figure out where the problem areas are.

“It’s more than just putting a spreadsheet under someone’s nose and saying, ‘Hey, work on this,'” Eichler said. “There is a need also for meeting people where they are and understanding what the concerns are advocating for that, and the data is part of the advocacy work.”