The daily trek felt like an adventure for a while, but it eventually took its toll on the Baltimore native. Cherry Hill, created by Black military veterans in the mid-20th century, lies near Baltimore’s southernmost tip; Solomon-DaCosta’s now-defunct middle school, about five miles east of Downtown, is difficult enough to reach without having to cross the Patapsco River as she did.

Yet the long ride taught her a form of resilience, said Solomon-DaCosta, now 40: “I was a kid so it was kind of like an adventure. Sometimes it felt like a burden, but as a young person it made me more observant.”

Solomon-DaCosta’s heightened scrutiny helped her realize that she was growing up in poverty as well, layering a constant sense of disquiet on top of her growing anger toward the systems that put her family in this position — systems she’d only come to understand more as an adult.

“As a young person, I could feel when we were at the end of the month,” Solomon-DaCosta told Technical.ly. “I knew what it felt like to have to negotiate how we would pay certain bills. The bills would get paid, but there wasn’t a sense of ease. We were poor, but it was just a way of life.”

Baltimore’s barriers

In Baltimore, stories like Solomon-DaCosta’s — of Black families stuck in poverty following decades of structural disinvestment — aren’t uncommon.

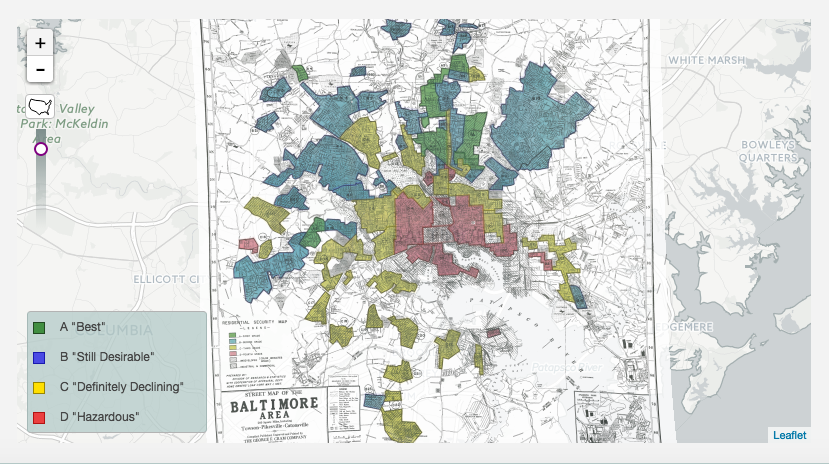

In the early 20th century, housing discrimination ramped up in the city as homeowners associations, housing ordinances and block-busting prevented Black people from owning homes. Then, in the late 1930s, the New Deal-birthed Home Owners’ Loan Corporation created residential security maps — which assessed investment risk for all of Baltimore’s neighborhoods — as part of the federal government’s program of housing and mortgage relief.

Black neighborhoods were almost exclusively “redlined,” meaning they were given poor financial grades and marked in red, so investors stayed away. This not only segregated the city but began a cycle of unequal access to resources, poor public safety, high crime rates and suppressed wealth creation for Black residents that exists to this day.

HOLC’s map of Baltimore. (Screenshot via Mapping Inequality)

With the city lacking resources and outlets for releasing pent-up frustration, many people turn to the life of crime since it’s easily accessible. The homicide count for 2022 was 333, cementing a multiyear trend of 300-plus homicides.

Yet Baltimore isn’t defined by these brutal conditions. Economic advancement does happen here. Baltimoreans embrace the adversity that comes along with living in the city and use it as motivation to overcome the obstacles in front of them.

What does it mean to thrive for Black middle-class residents in Baltimore?

Technical.ly spoke with Solomon-DaCosta and four other successful Baltimoreans for this installment of Thriving, a yearlong reporting series highlighting the lived experiences of people in Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Milwaukee, and other comparative cities to understand what it takes to rise above life’s everyday obstacles.

The five people you’ll meet below represent fields including business, writing, film, art and technology, and each consider themselves middle class or above. Despite their unique professional backgrounds, they all seek fulfillment in a similar way: Their joy stems from using their voices and capital to create a more equitable city not just for them, but for future generations.

For Solomon-DaCosta, for instance, it’s not feasible to advance her own life without uplifting her community along the way: “I can’t think about thriving without thinking about my kin, my community, and the people around me,” she said. “I think about how my life in Baltimore has been touched by race, class and gender.”

These are their stories.

Jess Solomon-DaCosta: ‘I learned how to adapt’

As she entered adulthood, Solomon-DaCosta began educating herself about the litany of historic problems — redlining, insufficient public safety and economic segregation among them — that weighed on Baltimore residents, especially Black ones. This exploration led to her earning a bachelor’s degree in communication studies and African American studies from the University of Maryland, College Park.

“I started to wonder if that was connected to where I live or not,” Solomon-DaCosta said about these conditions she increasingly understood.

Jess Solomon-DaCosta. (Photo by D. Finney Photography)

In order to simply function in her daily life, she taught herself how to camouflage her resentment against the systemic issues that plagued her community: “Becoming a chameleon allows me to talk about my different experiences,” she said. That built-up rage consumed her early in her career while she was working for social justice nonprofits, making her “feisty” and constantly angry. But her desire to uplift her community never waned, leading her to create her own solution.

In 2015, Solomon-DaCosta founded Art in Praxis, an organizational development firm that helps philanthropic sector players like foundations, institutions and social justice groups strengthen the impact of their work. This work involves addressing these entities’ internal cultures and workplace dynamics that, despite best intentions, can reinforce the very discriminatory structures they seek to eradicate.

“Businesses that do great work also deserve to have places that feel good for their staff,” Solomon-DaCosta said. “We’re behind the scenes working with progressive leaders and organizations that want to be better, more thoughtful, more impactful and want to be creative about how they get to that point.”

“For me, thriving means you have options.”Jess Solomon-DaCosta

From Solomon-DaCosta’s adverse childhood to attaining her status as a key player in Baltimore’s robust ecosystem, she finds that true fulfillment comes from having the ability to choose how she lives her life.

“For me, thriving means you have options,” she said. “You can pick and choose your schools, healthcare, where you eat, public safety, and if I live in a certain neighborhood not being subjected to just those conditions.”

Solomon-DaCosta hopes to pivot Art in Praxis toward supporting product-based companies to generate more revenue so it can expand its outreach over the next year. She sees her work as an unending battle, but that doesn’t mean she won’t take an occasional break.

“We need to rest while we do this work,” she said. “I don’t get as charged. I think about what I can do to catalyze and change things from where I sit. I’m also learning how to be unattached in some ways. I don’t want to metabolize this stuff. I can’t hold onto these distractions. Toni Morrrison talked about how racism is a distraction.”

D. Watkins: ‘If [my story] has a place, then yours definitely has a place’

Watkins was only 27 years old when he received a book from a trusted friend that changed the trajectory of his life.

It was “The Coldest Winter Ever” by Sister Souljah — a novel about a young woman living with a drug-dealing family. The book resonated with him due to his own harrowing experiences growing up in a narcotics-filled environment in East Baltimore. Watkins loved storytelling since he was a child, but didn’t realize it could offer a viable career path until he quickly finished the book.

“I wasn’t used to seeing people read like that,” he said. “I was bored with the TV and she thought I would like it. I never knew you could write a book like that. I got into reading everything until it spiraled into a career.”

D. Watkins. (Courtesy photo)

Watkins, 43, read anything he could find and started interacting with people outside of his social context as well, shifting his perspective on his life. Coming to the realization that he grew up in poverty while simultaneously developing his skills as a writer recontextualized the world around him.

He realized that the War on Drugs made people all around the world faced similar struggles, such as losing loved ones to addiction, seeing friends sent to prison for years and gun violence.

“It made the world smaller,” he said. “Even though I was open to brand new experiences from reading, the world got smaller because I found out people on the other side of the globe was going through the same thing. As unique as my urban experience was, there was so many people that had similar experiences and been through similar things that I had to get through.”

From there, he published multiple essays addressing the inequities in the city and went on to become a New York Times bestselling author while earning lucrative income in the process.

Now, Watkins’ books “Black Boy Smile” and “The Beast Side” — which discuss the complexities of growing up in Baltimore through candid recollections of his own experiences — are taught in schools throughout the city. He also uses public speaking to share his story and offer young people guidance.

Seeing his own writing impact Baltimore’s schoolchildren is a full-circle experience that never gets old for him.

“I come from a place where there are plenty of talented people who don’t really get a shot if they don’t have connections. Poor people don’t really have connections.”D. Watkins

“I still can’t believe it,” he said. “Coming up, we’re taught that our stories don’t really matter so I can’t believe that it’s being taught and celebrated. … I want them to discover the power of critical thinking and that reading is the only way to strengthen that. I want them to be empowered to tell their own stories. If mine has a place, then yours definitely has a place.”

Watkins is a writer for “We Own This City,” an HBO series from “The Wire” creator David Simon that highlights the rise and fall of the Baltimore Police Department’s Gun Trace Task Force. He and casting director Thea Washington, both East Baltimore natives, hired over 5,000 local residents for the show. This provides an opportunity for commonly overlooked people.

“Thriving means having enough power to elevate people,” Watkins said. “I come from a place where there are plenty of talented people who don’t really get a shot if they don’t have connections. Poor people don’t really have connections. That just kind of sets the tone and that’s just the difference.”

Moving forward, he wants to use his prominence to shake up Baltimore’s depiction in the media by highlighting positivity around the city more.

“Time and trust are big things that it takes to make that a reality,” he said. “The feel-good stories aren’t promoted enough. When somebody does something good, the same outlets cling to that same person. Nobody’s doing the work they should be doing.”

Tammira Lucas: ‘We don’t have to be a product of our environment or our upbringing’

Strolling around West Baltimore was nothing more than a daily childhood occurrence for Tammira Lucas. To her, it wasn’t a crime-filled neighborhood. It was just home.

But during her time at Villa Julie University, which is now named Stevenson University, she became aware of the infrastructure relegating Baltimore residents into poor conditions.

While facing the reality of her own impoverishment was a crushing blow, striving to change the narrative about her community gave her direction.

“I was so perplexed and I still struggled with this,” said Lucas, now 36. “We don’t have the same rights or opportunities that others do. It was very disheartening because people look at us instantly and there’s a whole perception of us. ‘They’re poor. They’re not smart.’ It’s always been challenging to overcome the feelings of that and it fueled the fire under me.”

Tammira Lucas. (Photo by Todd Dorsey)

In 2016, Lucas cofounded the National Association of Mom Entrepreneurs, which offers an eight-session program that provides entrepreneurship training for mothers. She also cofounded The Cube, a coworking space that provides a staffed play area so entrepreneurs can spend time with their children while working.

Lucas said learning about the systemic issues permeating Baltimore inspired her to attack those challenges head-on. Though she was infuriated when learning about the barriers that exist to keep people of color disenfranchised, she made it her mission to prove that she could determine her own destiny — achieving wild success and moving past the middle class along the way.

“Thriving means you are living the life that you get to wake up and do whatever is that you want to do how you want to do it,” Lucas said. “I live the life that I want and not the life that society tells me I should have. My focus is never chasing the dollar. It’s chasing the purpose. My happiness comes down to, ‘Can I hop on the phone tomorrow and go to the beach?’ Yes, I can.”

For now, Lucas and her sister look to grow their businesses and build a foundation for her 13-year-old daughter Ryann and her niece Martesha to take over once retirement appears on the horizon.

“It’s their responsibility to take it on and move it forward in a way that they see best fit,” Lucas said. “Hopefully, we’ve instilled enough in them to talk about wealth and they’re not going to take any field where they’ll exit without setting themselves up successfully.”

Tammira Lucas. (Photo by Todd Dorsey)

Eden Rodriguez: ‘I love to show up at a place where I can be myself’

Eden Rodriguez, 29, moved to Baltimore in July 2021 to join EcoMap Technologies as head of people operations. Just one month later, she learned how crucial it is to keep your antennas up when navigating everyday life in the city.

Rodriguez and her partner were packing for a trip to South Carolina. They’d loaded up the trunk and went back inside to chat, but their suitcases and bags were all stolen when they came back out just a few minutes later.

Coming from the small town of Canton, Georgia, which has a population of around 35,000 people, Rodriguez didn’t need to worry about petty criminals scouring her neighborhood. Instead of letting this incident distort her perception of Baltimore, she used it as a springboard to become more vigilant.

And now that she has adjusted to living in the city, she fully embraces everything Baltimore has to offer — even if it means learning which areas to avoid.

“I have to remind myself to be aware of which street I’m on,” she said. “Do you want to cut down that alley? That’s something I wouldn’t have thought about before. I have had to become a bit more aware of that, but the communities that I’ve found here in Baltimore have felt like my small town. They envelop you a bit and give you shelter. People do care about each other here. That feels familiar to me.”

Eden Rodriguez. (Courtesy photo)

EcoMap offers a platform that curates data from various ecosystems by tagging information with keywords, providing a centralized pool of information for users. In one notable example of the company’s work, a map of Dallas’ financial resources helped city officials see the dearth of banking institutions in an area made up of mostly Black and Hispanic people, which eventually led to banks opening up in that area.

“We want to create equity in the ecosystems we’re in and make sure that information is accessible,” Rodriguez said.

Rodriguez thrives through problem solving like this and by finding people who fit the company’s culture, which emphasizes an openness about both success and areas of improvement.

“There’s impact that I’m making in terms of the people that we hire,” she said. “I love to show up at a place where I can be myself. If I’m having a bad day, I can let my leadership know that. There’s a lot of accountability and transparency here. There’s never a time where I don’t want to go to work because of the work. I don’t show up and want to go home.”

Rodriguez also serves on the board for Baltimore Tracks, a coalition of Baltimore-based tech company leaders that aim to increase opportunities for people of color in tech. Whether it’s through her work for EcoMap or planning for Baltimore Tracks, she strives to create opportunities for minorities in the city.

“Baltimore has a lot of good stuff going for her,” she said. “Baltimore is 60% Black and the tech community is not representative of that, so being able to give other people in the tech space the tools needed to find that diverse talent, hire them and train them would be a really cool part of my legacy here in Baltimore.”

Elissa Blount-Moorhead: ‘Thriving is being able to have the space to engage and build’

Elissa Blount-Moorhead, 54, found what was important to her at an early age.

Her family moved from their hometown of Brooklyn to Washington DC during her formative years. Growing up in DC during a period of liberation movements, communes, art movements and rising Black nationalism molded her.

Blount-Moorhead said constantly interacting with people who shared similar worldviews helped elevate her thinking since she had the freedom to explore whatever she wanted without the fear of judgment from those around her.

“The multiplicity of our diaspora was all we really saw so it felt pretty utopic,” she said. “I felt very immersed in the community and very accepted.”

Elissa Blount-Moorhead. (Photo by Schaun Champion)

Blount-Moorhead’s father was a radio host and her mother is a photographer and artist, so she was naturally inclined to pursue an artistic career. In 2014, she moved to Baltimore as a partner in NYC’s TNEG film studio, which focuses on creating Black cinema.

“Thriving is being able to have the space to engage and build,” she said. “Sometimes, those are physical resources or even intellectual resources. That safety is thriving to me.”

Blount-Moorhead believes systemic issues that remain prevalent in Black communities around the country such as redlining, mass incarceration and food deserts won’t destroy the Black community so much as ruin society as a whole.

“It’s all one thing — anti-Blackness,” she said. “Anti-Blackness is the destruction of the country, not just of Black people. Black people are going to keep doing what they do even if half of us fall.”

“I’m interested in finding humor in the everyday life.”Elissa Blount-Moorhead

Rather than let the plight of those issues crush her creative motivation, Blount-Moorhead is digging deep to find the humor in these corruptions by creating a Baltimore-set dramedy show with her sister, writer Ericka Blount Danois. They’re currently working to green light the show, and though they remain tight-lipped about the premise for now, they look to highlight the unique personalities that comprise Baltimore to shift the city’s narrative away from being known for high crime rates.

“The city has a lot of dimensions and a lot of multiplicity that’s not reflected,” Blount-Moorhead said. “We see a lot of crime and beleaguered ideas around crime. I’m much more interested in multidimensional people. What always interests me is being able to laugh at the unlaughable. I’m interested in finding humor in the everyday life.”

Now, Blount-Moorhead and a group of fellow creatives are working toward closing a deal to acquire a building in West Baltimore for their Lalibela project. Lalibela will serve as a hub for film projects, but will also feature technology programs, a farm and reproductive health services — providing a space for local talent in various fields to hone their crafts.

“It’ll provide a platform for us to make in a sovereign way,” she said. “Folks who are born here and feel like they have to leave to New York or LA will have a space to work together here and stay in Baltimore.”

This report is part of Thriving, a yearlong storytelling initiative from Technical.ly focused on the lived experiences of Philadelphia and comparative city residents. The goal is to generate insights about the economic opportunities and obstacles along their journeys to financial security. Here's who we're focusing on and why.

Before you go...

Please consider supporting Technical.ly to keep our independent journalism strong. Unlike most business-focused media outlets, we don’t have a paywall. Instead, we count on your personal and organizational support.

Join our growing Slack community

Join 5,000 tech professionals and entrepreneurs in our community Slack today!

The person charged in the UnitedHealthcare CEO shooting had a ton of tech connections

Delaware students take a field trip to China using their tablets and ChatGPT

From rejection to innovation: How I built a tool to beat AI hiring algorithms at their own game