If you were going to judge the City of Philadelphia’s involvement in the buzzy good government movement of the past five years, you’d need some way to evaluate how much of its agency data is shared. Until the launch of OpenDataPhilly.org this afternoon, it’s not entirely clear where you would have started.

The web and its users, some progressive governments and their constituents have all conspired together in the past half decade to set a precedent troubling for others: the data and information, numbers and calculations, charts and graphs that government institutions have collected for a century or two should be made available for public consumption.

The city governments of Washington D.C., San Francisco and London are leading the way, creating agency workflow that incorporates the Internet and uses it to share its practices and data collection as a norm.

This year, New York City followed its BigApps contest — built to spur third-party development around city data — by unveiling a real-time 311 request map and plans to put QR codes on building permits by 2013. Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake signed an executive order compelling agencies to post its data online, and Raleigh, N.C. has made a case for open source technology.

More broadly, the Canadian federal government has launched a data catalog of its own, following Data.gov, championed by the Obama administration.

Now, with the April 25 unveiling of OpenDataPhilly.org, the City of Philadelphia has made a great, albeit perhaps belated, step forward. The puzzling part seems to be how little the city actually had to do with it.

WHAT OPENDATAPHILY.ORG IS

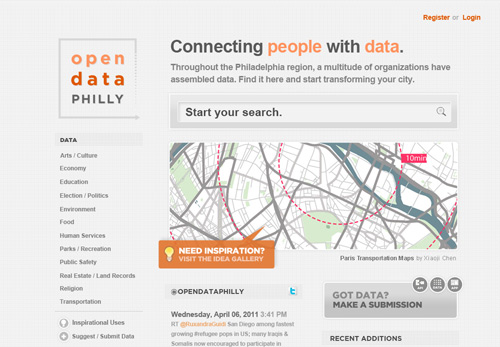

OpenDataPhilly is a searchable website that aims to be the central resource for all relevant, civic orientated tools, applications, data and information in the region from both governmental and non-government groups. What that means is if you’re the type to look at an Excel spreadsheet full of data points, or files listing longitude-latitude markers, and you see the potential for visualizations or content for applications, you finally have a starting point.

To be clear, there really isn’t anything new on OpenDataPhilly.org just yet. Its point, the man behind its creation says, is in its ability to finally track what is already out there and make clearer the interest for more data to be made available.

“This just needed to be done to actually begin talking about what comes next,” said Robert Cheetham, the founder of Azavea, a small geospatial and geographic data application development company based in a renovated brick warehouse at 12th and Callowhill streets. “It’s been the clear first step for a long time.”

The actual files aren’t hosted on or anywhere associated directly with OpenDataPhilly. Instead, the site is kicking off as little more than a card catalog of what various city agencies already host publicly, either out of individual effort or by some specific requirement or policy to do so.

To start, the site catalogs dozens of initial data sets, APIs and data-centric mobile and web-based applications, including things like city property parcels, Cheetham said.

Coders, developers, designers and their ilk, emboldened by a decades-old open source movement, tend to like to build tools and displays using meaningful information and share them with the world, sometimes for money, but often for nothing but their use.

At its best, this broad community helps create online, mobile, software and even desktop applications that can better help journalists, academics, legislators, researchers and the curious to visualize, contextualize, quantify, understand and explain the world around us. Communities can be better served, governments can be made more efficient and transparent and we can all be made more aware, educated and decisive.

“This is the future of accountability,” says Chris Satullo, the Executive Director of News and Civic Dialogue at WHYY who has taken interest in the project.

Simply put, good data can inform action that makes our lives better, an end goal that, you know, used to be the sovereignty of the state alone.

WHO IS BEHIND OPENDATAPHILLY.ORG

To date, the City of Philadelphia hasn’t spent a dime on ODP.

The construction of the site’s look, feel and functionality came by way of a pro bono effort from Azavea, on the call of founder Cheetham, a precise and wonkish self-described geek, with gray hair and a folding bicycle.

It’s a project he says he’s long thought needed to be done.

“Philadelphia has had many public data sources for more than 10 years, but there hasn’t been a place to bring it all together,” Cheetham says. “This is intended to do that, thereby making it easier for developers and other people to use that data in useful and inspiring ways.”

In truth, Cheetham’s work isn’t selflessness under glass. A not insignificant portion of Azavea’s funding comes from local government contracts, including the City of Philadelphia. Continuing a nearly unrivaled reputation for handling data-driven GIS builds for his hometown is surely no small feather in his cap. But he was brought on the project for that reputation.

It was mid-January 2011 when a handful of civic-minded technologists met in the darkly lit lobby of the Phoenix Building at 16th Street and the Ben Franklin Parkway. Cheetham, Mark Headd, an open gov organizer and hobbyist hacker from national VoIP carrier Voxeo, and Nathan Solomon, the founder of virtual currency startup Superfluid, were brought together, with this reporter, by Roz Duffy.

By most accounts, Duffy, the user-experience designer who built a reputation by bringing national tech events to Philly — Refresh Philly, Barcamp Philly, TEDx Philly — proved a natural convener.

“I needed to bring [them] together, step back and see what could happen,” Duffy said then.

These and others took hold of the initiative. designer Johnny Billota, a regular at Old City coworking fixture Independents Hall, branded an early version of the initiative’s logo, and other stakeholders shaped priorities. Technically Philly offered audience: helping to organize the Philly Tech Week ODP unveiling and, with Headd, an Open Gov Hackathon at BarCamp NewsInnovation April 30 to bring together coders to use the data.

“This is the beginning of the open data movement in Philadelphia,” says Division of Technology Chief of Staff Jeff Friedman.

Jeff Friedman speaking to Robert Cheetham at a March 22 Philadelphia Technology Leaders Breakfast organized by Technically Philly. Photo by Neal Santos.

THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA’S ROLE

If nothing else, former city Chief Technology Officer Allan Frank put a mark on leading IT initiatives for the City of Philadelphia during his tenure from summer 2008 to this February. Data was part of the talk.

Under his reign, Mayor Michael Nutter consolidated all government IT, previously governed by individual agencies, under the purview of Frank, who became the city’s first CTO in summer 2009. With greater control and a fatter budget, Frank took a vague message to the people: “Digital Philadelphia.”

By fall 2010, Frank had the pitch down pat. Digital Philadelphia was a broad vision meant to encompass the three biggest ways technology could improve Philadelphia: creating jobs, increasing access for lower income individuals and boosting government transparency and efficiency.

OpenDataPhilly.org, a branded searchable portal for city data, then, is a major accomplishment in an overall movement that has been reliably slow moving. That’s a big win coming from a relatively small group of volunteers doing so as a side project in fewer than six months.

“We start with the premise that we don’t necessarily know everything or have all the answers and we want to rely on this community for ideas,” Nutter told Technically Philly in July 2010.

“This isn’t really work that we’d be definitely doing in house anyway,” says DOT’s Friedman. “So we want to play the support role.”

That’s a role the city has played.

Beginning in June 2010, the city’s Division of Technology with Fuzebox consultant Paul Wright convened a stakeholders group of mid-level city officials; technology community members like Duffy, Headd and Bilotta; nonprofit partners and other residential voices. By the end of 2010, there was a push to release some data from three broad areas: non-emergency service line 311, geospatial parcel files and crime numbers. But an internal deadline was missed, and the group was searching for a new one.

In January, the group set its sights on Philly Tech Week as a launching point for something. Cheetham was pulled into the meetings and, frustrated by the lack of momentum on something as actionable as highlighting what data sets are already available, offered to move, leveraging an asset survey commissioned the previous year by WHYY for its NewsWorks.org website.

“This is the low-hanging fruit,” Cheetham says, “that can lead to more substantive gains.”

THE FUTURE OF OPENDATAPHILLY.ORG

Like with most good government initiatives, you’d be hard-pressed to find a clear and consistent opponent to utilizing the web to share government data and information. The question at hand is one around priorities.

Tommy Jones.

“I knew capacity was an issue when I came here, but I had no idea how bad,” says Tommy Jones, the interim Division of Technology CTO, whom predecessor Frank poached from Washington, D.C. city government. “I have two people in my network group here. In D.C., I had 13.”

Philly’s city government is still ‘in its infancy’ when it comes to sharing data, Jones says. While OpenDataPhilly is a novel way to start, showing off what work has already been done, Jones says there are hurdles still in the way to getting new data. The city doesn’t yet have a consistent, secure place to host its data, there are still cultural concerns in some agencies around the issue and a debate hasn’t yet been settled on if raw data is really what should be shared.

“Philly is taking on so many challenges at once because we have no choice, so the individual progress seems very slow,” Jones says. “I don’t blame [residents] for being frustrated, I’m frustrated, but I’m closer to it, so I understand why.”

So, how big of a priority is getting data out there?

For one, City Councilman Jim Kenney, who is credited with bringing the 311 concept to Nutter during the 2007 mayoral campaign, says it can’t be a top initiative, “maybe a five on a scale of 10,” he says, when compared to crime prevention, education and the like. Councilman Bill Green has bigger concerns about how accurate or consistent any city data can be.

“Most of city data would come from inefficient or ineffective systems,” Green said in January. “So pick something. We just need to draw a line in the sand and say, ‘from this date on, we’re only taking electronic forms [and move forward from there.]”

Perhaps a bigger concern is that no one person owns the initiative.

For now, the ODP site and domain name is in Cheetham’s hands. Individual city agencies have their own protocols and standards. Jones is the interim CTO but has said his top priorities are foundational elements, like network infrastructure and the city’s IT help desk, not highlevel good government initiatives.

Managing Director Rich Negrin, who oversees DOT, 311, inter-agency accountability program PhillyStat and other good government initiatives from the city, said it’s a balancing act between initiatives in his office.

“We still need to develop the backbone,” Negrin, who is speaking on transparency through technology at Friday’s Philly Tech Week Signature Event, said in March. “That way we can do the big lift.”

Cheetham has said Azavea isn’t the logical place to maintain ownership of any of it.

“This should be a collaborative initiative, not something from one group or business,” he says. “The city has to host the data, but it’s proven not very good at getting anybody to use it or know it’s there.”

There are other possible, sensible owners. Jones has talked about partnering with a large IT company that could securely host the data, like a Microsoft or an IBM, and then perhaps have a limited interface to cull through it. WHYY has taken interest in the data space, in connection with its push online with NewsWorks.org. The William Penn Foundation is funding a new Center for Public Interest Journalism at Temple University to be operational by year’s end and data will likely play a role. [Full Disclosure: Technically Philly receives funding from William Penn Foundation.] There are any number of advocacy or nonprofit groups that would happily steward the ship.

Whatever the future, it seems likely there will be a relationship between the city and some private enterprise.

“The value of what we’re doing is around breaking down the walls between ‘the public’ and ‘the government’ and working collaboratively, in full partnership, to advance an important set of related initiatives,” says Friedman.

That much is sure. While the city slowly, subtly made some of its data public beginning in the 1990s, the public face that may, for the first time, really see regular outside interest and use, is coming from pro bono support from a development firm, with help from a couple of news sites.

“It’s government as platform, facilitator, supporter of important work, not necessarily ‘doing’ all of it. More steering, less rowing,” says Friedman. “We’re reinventing urban governance.”

Join the conversation!

Find news, events, jobs and people who share your interests on Technical.ly's open community Slack

Philly daily roundup: Earth Day glossary; Gen AI's energy cost; Biotech incubator in Horsham

Philly daily roundup: Women's health startup wins pitch; $204M for internet access; 'GamingWalls' for sports venues

Philly daily roundup: East Market coworking; Temple's $2.5M engineering donation; WITS spring summit