Technology can be a tool to both spread and combat disinformation.

Partnership to Advance Responsible Technology (PART) held its inaugural Responsible Technology Summit on Tuesday, bringing together tech leaders from the Pittsburgh region and beyond for a day at the Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens.

The in-person event came two years after PART initially planned to host a conference, Executive Director Lance Lindauer said in his opening remarks, with the pandemic throwing a wrench in those hopes for 2020 and 2021. The conference comes several months after the org released a comprehensive report on how to responsibly grow Pittsburgh’s tech economy.

Now may be a better time than ever before to host a goal-oriented conference on “responsible” tech. The increasing polarization of American (and some international) politics, the economic dominance of large tech companies, the volatile stock and job market and the rampant disinformation online all point to a need for urgent action against reckless use of fast-changing technology.

The event featured a panel on disinformation and technology, a fireside chat on AI engineering for change, a point-counterpoint discussion on individual readiness and economy preparedness, and a keynote address from Renée Cummings, an instructor and data activist at the University of Virginia.

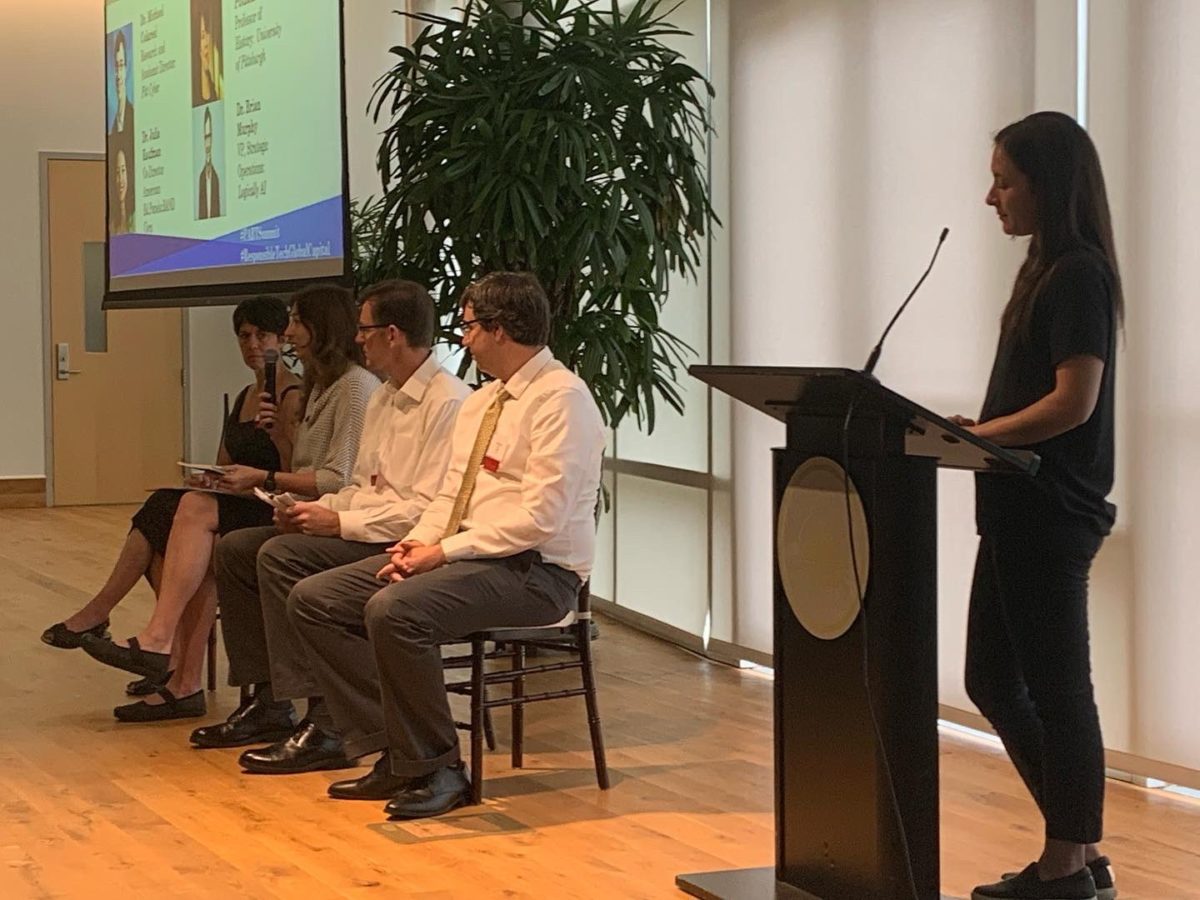

Technical.ly plans to share the highlights of each of those in focused stories. First up, here are some of the biggest takeaways from the discussion on disinformation and tech. Featured speakers included RAND Corporation Senior Policy Researcher Julia Kaufman, Pitt Cyber Research and Academic Director Michael Colaresi, University of Pittsburgh Professor of History Lara Putnam and Logically.AI VP for Strategic Operations Brian Murphy. The panel was moderated by 90.5 WESA Reporter An-Li Herring.

What’s the difference between disinformation and misinformation?

In academia, “disinformation, generally we think of as being something that is untrue, and the person who’s sending that message or that signal knows it’s untrue, so it’s an intentional lying or deception that’s going on” Colaresi said. “Misinformation is a passing on of signals and messages that people will interpret and possibly get wrong, but it doesn’t have to be intentional.”

It’s important to understand the difference to effectively combat the unique issues that each can create, he argued. While there are people and organizations that are actively and knowingly spreading false information, that is a separate issue from people who are, for example, sharing links to news stories or research papers on social media, but posting them with messages that are incorrect or out of context.

Widespread misinformation was arguably not as significant of a problem before the onset of social media, which has made it much easier for people to share misinterpretations of fact-based sources. And while some social media platforms have started to flag false content, it’s hard for content warnings alone to really take control of misinformation issues, particularly because they can be vaguer than disinformation-related ones.

What is the root cause of disinformation and its overlap with technology?

“That’s a very broad question,” Murphy said in response to Herring’s inquiry on how disinformation online got its start. “For decades, we’ve seen a decline in trust, we’ve seen the deterioration of organizations, we’ve seen the rise of the question of, ‘What is truth?'”

All of those factors run headlong into communications, which is the foundation of many social media platforms and news organizations. And while the elements for a perfect storm had been lingering for a while, Murphy points to the launch of so many social media platforms at once as the origin of this more recent crisis in disinformation.

“When social media came around, people weren’t thinking, they weren’t planning the way that this conference is about how do we make very profitable [new technology] and still have governance around it,” Murphy said.

Kaufman echoed his points, pointing to what she and her colleagues at the RAND Corporation have coined as “truth decay.” There are a number of factors that have contributed to it, but specifically, Kaufman named “the rise of more disagreement between what is fact and what’s opinion, an increasing volume of opinion out there in the world over fact, and the polarization of the United States.”

How can disinformation be combatted effectively?

Having a central organization and policy from the federal government would be ideal, all panelists agreed. Right now, there are “a lot of players and no coach,” Kaufman said.

“I think the core message here is that it can’t be an individual responsibility to combat disinformation,” Putnam said. Knowing that, “we need to think about a systemmuric approach that over time shifts the incentives.”

That approach may not come from the federal government any time soon, with many members of Congress themselves being sources of disinformation. Because of that, Putnam said, “we need to lean into a recognition that civil society and community organizations are absolutely critical players.”

Sophie Burkholder is a 2021-2022 corps member for Report for America, an initiative of The Groundtruth Project that pairs young journalists with local newsrooms. This position is supported by the Heinz Endowments.Join the conversation!

Find news, events, jobs and people who share your interests on Technical.ly's open community Slack