People may be the best city planners for their own neighborhoods. It’s hardly a novel thought, but it’s one that can become increasingly realized through technology.

Bushwick’s own mapping startup, CartoDB, recently released a white paper on the issue of smart cities and how they can be more responsive to the needs of residents and visitors: Urban Insights: an Analysis of the Future of our Cities and Technology. It’s worth a read.

“Leading smart cities are now welcoming citizen co-creation methods as the next evolution in smarter cities,” the report says. “The ideal vision for smart cities is one where infrastructure and services are connected with technology to empower informed citizens and government officials across agencies as partners. Civic engagement is mobilized by the best smart city/future city paradigms, where citizens are active stakeholders in policy that produces sustainable results.”

And, really, why would city planners or lawmakers know better how the systems of a neighborhood work than do the people on the ground?

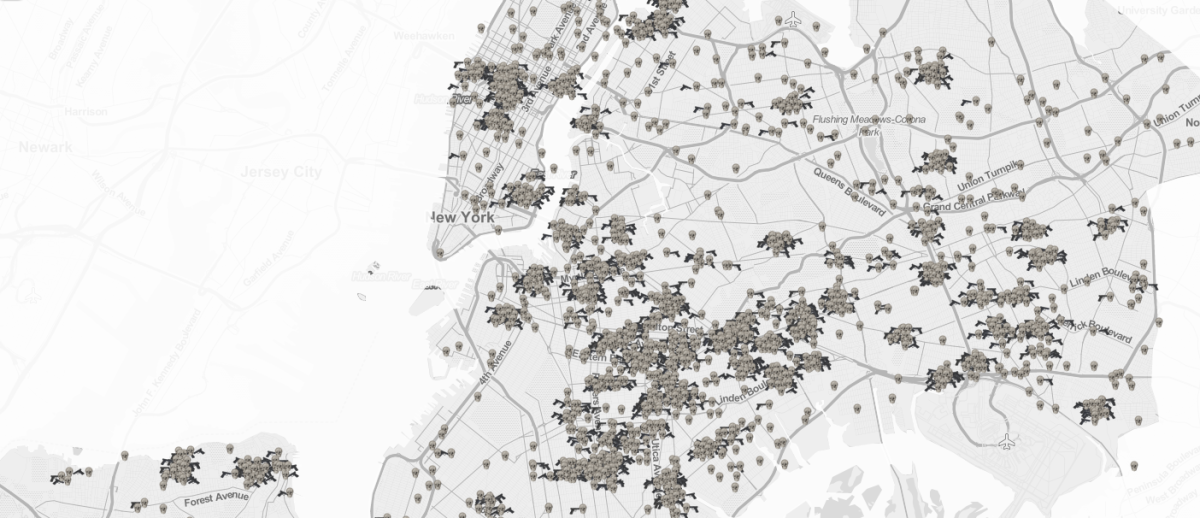

Death Map NYC by Zach Schwartz shows the site of each homicide and motor vehicle death in the last two years. (Screenshot)

In his 2012 book, Two Cheers for Anarchism, Yale professor James C. Scott discussed the difference between what he called the “official order” and the “vernacular order.” Essentially, he described the official order as those rules and systems decided on by lawmakers and institutions, and the vernacular order as the informal rules that people on the ground actually follow. Scott finds that the vernacular order, which comes about without central planning and over time, is often more efficient than the organization passed down from above. He gave a good example of taxis and the rules of France.

“Workers have seized on the inadequacy of the rules to explain how things actually run and have exploited it to their advantage,” Scott wrote:

Thus, the taxi drivers of Paris have, when they were frustrated with the municipal authorities over fees or new regulations, have resorted to what is known as a greve de zele. They would all, by agreement and on cue, suddenly begin to follow all of the regulations in the code routier, and, as intended, this would bring the traffic in Paris to a grinding halt. Knowing that traffic circulated in Paris only by a practiced and judicious disregard of many regulations, they could, merely by following the rules meticulously, bring it to a standstill.

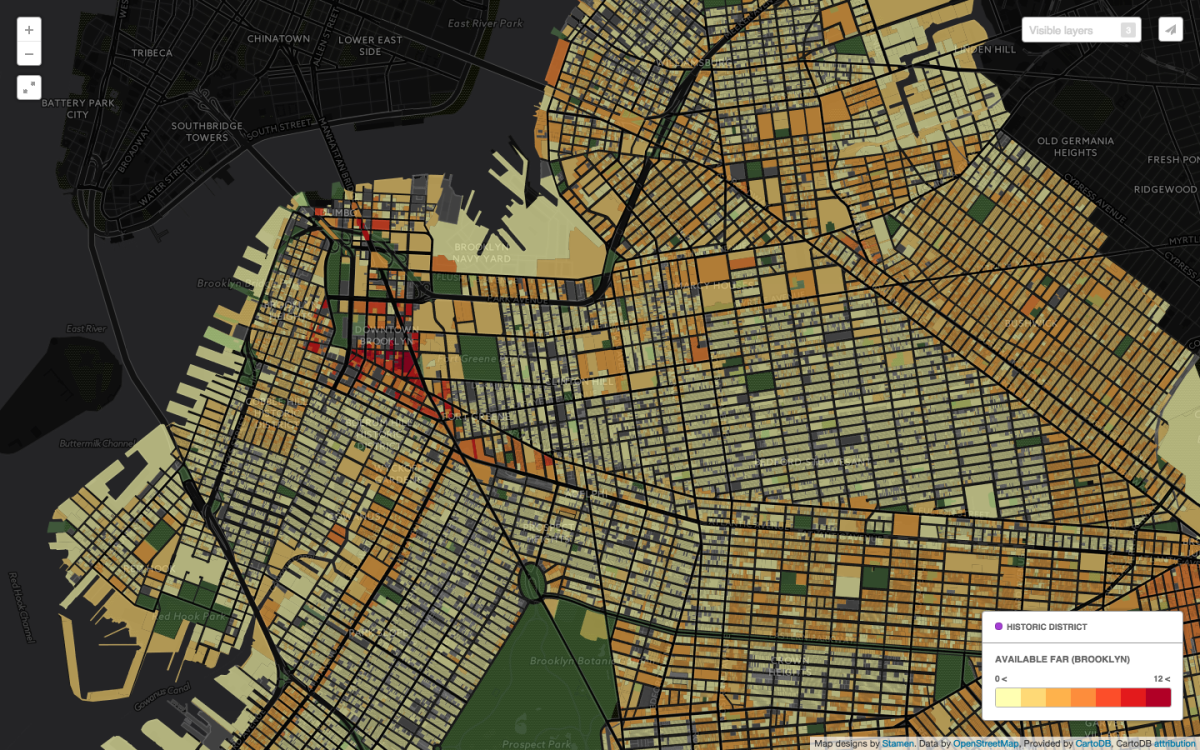

An example closer to home is the work of Curb Your Litter: Greenpoint. The organization uses a map (created on CartoDB) that allows residents to drag and drop trash cans to the spots in Greenpoint where there is the most litter. Working with different city and business groups, they hope to present their results to the city to show where the most efficient places would be to add trash cans, solving (they hope) the problem of litter on the streets, and saving the city money by not placing inefficient cans.

“Cities have benefited from making data sets public accompanied by a call for crowdsourced ideas and apps,” CartoDB continued in its Urban Insights paper. “The availability of data allows local civic hackers, developers and businesses to tap into the potential of data in providing free or paid services. Cities with smart open data strategies profit from providing readable and mobile-friendly data with Web APIs along with providing education and program visibility for citizens.”

Consider the Brooklyn-based Bikestorming mobile app, which, the report highlights, “uses open government data to increase the rate of cycling in cities.”

When people talk about the democratizing potential of the web or social media, they point often to events like the Green Revolution in Iran or the Arab Spring. But democracy happens on a local, quotidian level as well as it does in grand uprisings.

Having input into where you and your neighbors should be able to safely ride your bikes, toss your trash or navigate city streets is worth something. Feeling like you have a stake in your community is one way that people become citizens. When authority listens, you can’t help but trust it more.

Join the conversation!

Find news, events, jobs and people who share your interests on Technical.ly's open community Slack