There’s lots known about the Chesapeake Bay and how it sustains the Mid-Atlantic. When it comes to the many waterways that feed the vast estuary, however, the picture is often less complete.

For one, there’s the maps.

According to UMBC Professor of Geography and Environmental Systems Matthew Baker, existing maps from entities like the U.S. Geological Survey have a lot of the prime rivers and streams. But he sees a lot to learn from getting more granular about the watershed, which includes territory in six states and D.C.

“We have the veins mapped but these are the capillaries,” Baker said of the streams. “And they’re critical for that first transport of water, nutrients and pollution to the Bay.”

Baker and a team from the Annapolis-based Chesapeake Conservancy are setting out to create more detailed maps of that system. The effort recently received a $1.2 million grant from the Chesapeake Bay Program, which directs restoration efforts in the watershed. When it comes to conservation, the Chesapeake Bay Program is specifically interested in how more accurate maps could improve management of daily pollution limits set by EPA, according to UMBC.

Along with the work of mapping, the effort will involve developing new tools and tech-enabled methods to create the more detailed look.

“We want to make a map that captures streams as realistically as possible and is still cost effective to make,” Baker said.

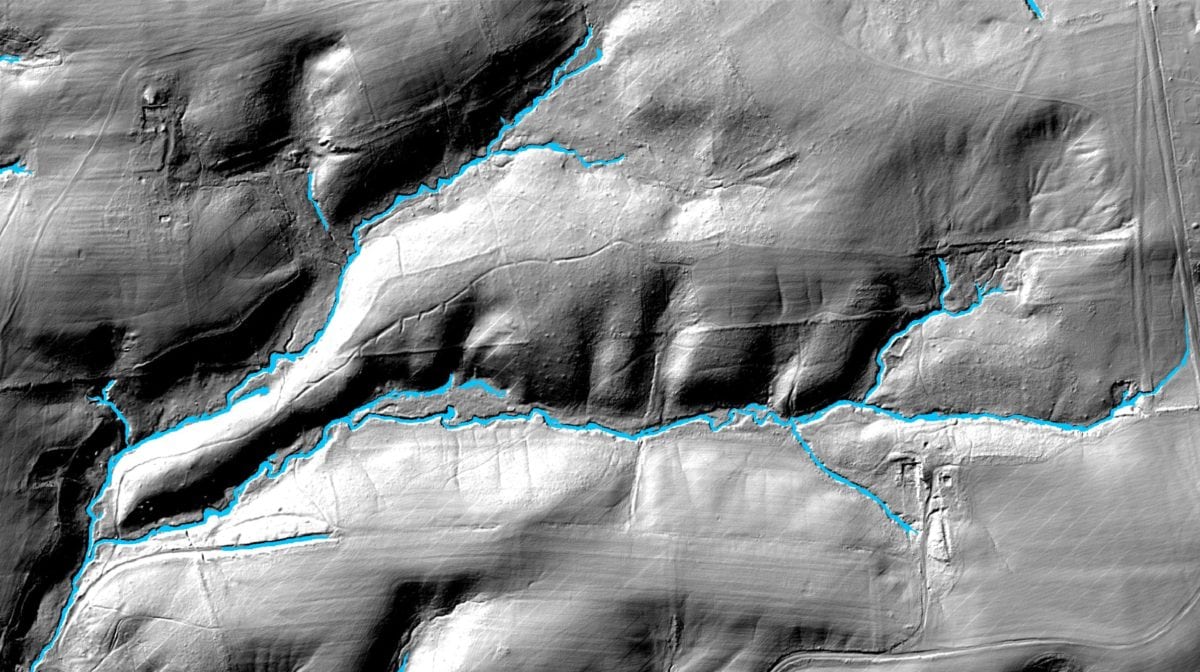

The team will analyze LiDAR data, and develop algorithms to automate the process of locating channels and identifying connections to form a stream. Another task will be cleaning up any anomalies in the data.

Baker acknowledges it’s a tedious process, and one that presents plenty of challenges. For instance, some of the channels are buried, making the streams appear disconnected. It could say a lot about how humans have changed the landscape, but getting it right takes a lot of detailed work.

An even bigger undertaking is the work of going out into the field, checking and updating. That process will take longer than getting the first draft of the map.

Mapping where a stream flows is tricky work. (Photo courtesy UMBC)

“That’s where the collaboration between the folks at UMBC and Chesapeake Conservancy is really important,” Baker said, explaining that skilled technicians from the Conservancy can assist both in the computer lab and in the field. Undergraduate students may get involved, too.

“If it’s done across a broad scale, really it’s never been done at this scale before to get this kind of map,” Baker said. “There’s a lot we can learn about the landscape and how streams form.”

Join the conversation!

Find news, events, jobs and people who share your interests on Technical.ly's open community Slack

Baltimore daily roundup: Gen AI's software dev skills; UpSurge Tech Ecosystem Report; MD service year program

Baltimore daily roundup: Mayoral candidates talk tech and biz; a guide to greentech vocabulary; a Dutch delegation's visit

Baltimore daily roundup: An HBCU innovation champion's journey; Sen. Sanders visits Morgan State; Humane Ai review debate